Soft Landing: Mission Possible?

Douglas Porter

July 14, 2023

Even for those of us of the inflationist persuasion for the past 30 months, there can be little debate that the June CPI was good news indeed for the U.S. economy—very good news. For the first time in over two years, most of the top-line figures could be considered “normal”. Whether it was the mild monthly headline rise of 0.18% and 0.16% on the core, both of which matched the pre-COVID 10-year median, or the yearly overall increase of 3% (less than a third of last June’s grotesque 9.1% peak), most of the results were back in familiar and much more comfortable terrain. One sticking point: while core was tamer than expected, it’s still up 4.8% y/y, and even the three-month trend is still just above 4%, a pace not seen since the early 1990s.

Despite that lingering quibble on core, markets seized on the inflation relief with both hands. After a tough couple of weeks, Treasuries rallied furiously, with two-year yields diving 20 bps after visiting 5% last week, and 10s falling even more to 3.8% after a look above 4% post-payrolls. Equities kept rolling, with the S&P 500 pushing above 4500 for the first time since March 2022, and now up more than 25% from last October’s nadir. And lest one believes this is just a tech story, the MSCI World Index is also up more than 20% from the lows, and now just 7% below the late-2021 peak. Even the TSX got into the game, rising more than 2% to back above 20,000. And, most currencies strengthened—the euro was up more than 2% this week—as the U.S. dollar lost ground on prospects of a less hawkish Fed.

One analyst said that the calm June CPI showed that the “fever had broken” for inflation. We would assert that, in fact, the fever broke last fall when energy prices cooled considerably and the supply chain normalized. But the question has always been how long the recuperation period would last. And while the latest figures are encouraging, the real battle begins now, as the easy base effects are now behind us. (Note that between last June’s 9% peak and this year’s 3%, inflation has averaged a towering 6% over the past two years, even with energy prices little changed on net over that period.) And while most were celebrating the lower inflation news, oil prices were quietly pushing back up to $76 this week, while gasoline prices continue to creep higher. Pump prices were down 27% y/y in June, alone carving almost a point from overall inflation; that cooling effect will dissipate in the months ahead.

As the disinflationary force of lower energy prices fades, that will leave us dealing with the underlying 4% trend in core. Slowing rents will almost certainly help, but to truly crack core will likely require a more significant slowing in the economy. On that front, most of this week’s indicators displayed ongoing resiliency. Small business sentiment perked up to its best level of the year in June, with a normal share reporting they plan to hire or increase capital spending. Initial jobless claims dipped again to below 240,000, and are showing no serious signs of stress after a spring hiccup. The one flash of potential softness was from consumer credit, which saw its smallest increase in nearly three years in May at $7.2 billion (versus a 12-month average of $23.8 bln), potentially signalling that consumers are fading after the wave of rate hikes. However, U of M consumer sentiment bounced in July to a near 2-year high, even as 5-year inflation expectations perked back above 3%.

Amid the latest round of economic data, we are making two changes to our forecasts. We are once again pushing out our call for a mild downturn in the U.S. economy by a quarter to Q4, which lifts this year’s GDP estimate two tenths to 1.7%, and pushing out the date of the first Fed rate cut to the second quarter of next year (as the resilient economy outweighs the better CPI news). We are making similar adjustments to the Canadian call—2023 GDP is now 1.6%, but next year is shaved to 0.7% as the downturn begins later. (This week’s Focus Feature looks at why the Canadian and U.S. outlooks are so similar despite the deep divergence in population trends.)

Similar to the Fed, we now look for rate cuts from the Bank of Canada to only commence in Q2 of next year. In fact, markets are not even sure that the Bank is done hiking rates after this week’s 25 bp move to 5.0%. While the statement and comments from Governor Macklem were mixed, the Bank did not close the door on possible further hikes, and it loudly pushed back the date at which it expected inflation to return to target by six months to mid-2025. The latter was likely aimed at preventing an eager market from pricing in near-term rate cuts, although the entire GoC complex still rallied heavily this week on the U.S. CPI, with the all-important five-year yield dropping 20 bps to under 3.8%.

Some analysts derided the Bank’s latest economic projections as fantasy, with the MPR landing well above consensus on growth this year and next, and calling for sticky inflation. But we would note that the Bank has been among the best on their relatively upbeat call on growth this year (no comment on people in glass houses and all that), and we are very much aligned with the Bank’s view on inflation. The big indicator for Canada next week is Tuesday’s CPI, and it is expected to be less friendly than the U.S. model for June. In fact, our call of a 0.4% m/m rise will shave the annual pace three ticks to 3.1%. In the event, Canada’s headline inflation will be above the U.S. for the first time since late 2019 (i.e., pre-pandemic days).

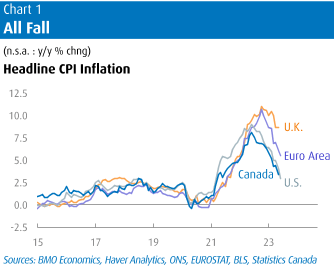

The U.S. looks to sport the lowest inflation rate in the G7 for June (Chart 1)—a truly rare event—as even Japan will likely stay above 3%. Yet, America is not alone with low inflation among advanced economies. South Korea and Denmark are now both below 3%, while each of Switzerland, Taiwan, Spain and Greece (!) are now below 2% on a yearly basis. The broadening of milder inflation trends suggests that the U.S. result is no fluke and increases the odds of a soft landing for the economy. Even we inflationistas must recognize that reality.

While the U.S. is at the low end of the G7, China has the lowest inflation rate in the world, with headline CPI dropping to precisely zero. A 5.4% y/y drop in producer prices and a sluggish recovery suggest inflation is going nowhere fast in that economy. Beyond inflation, arguably the second most important global economic indicator this week—China’s June trade figures—got lost in the shuffle amid the CPI results and the BoC rate hike. But the broad weakness is well worth highlighting, as exports slumped 12.4% y/y, while imports dropped 6.8%. The soggy trade data raise the risk that next Monday’s Q2 GDP data will come in light—the consensus is looking for modest 0.8% rise in the quarter, but up 7.1% y/y from weak year-ago levels.

China’s share of U.S. imports was already falling steeply even before this sour trade result. Aside from autos, almost all categories of goods are dropping steeply, likely reflecting a combination of slower global manufacturing activity and the consumer shift in spending from goods to services. But the deepening decline in China’s exports could be an early indication that the de-risking trend in Western economies is already beginning to bite. Certainly, foreign direct investment into China has seen a marked downshift, and the trade data may be a signal that something even more meaningful is afoot.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.