Seeking Canada’s Place in a World Transformed

The United States under Donald Trump is retreating from its role as a reliable, predictable, values-driven, rules-based leader on the world stage. While America’s democratic institutions process the constitutional implications of Trump’s corruption, Canada must re-evaluate its own geopolitical footprint. Former Conservative cabinet minister and current President of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce Perrin Beatty offered a way forward in the d’Aquino lecture, delivered at the National Gallery of Canada in November.

Perrin Beatty

Sixteenth century cartographers didn’t have anything like the mapping technologies we use today, so mapmakers often filled in unknown areas with illustrations of exotic creatures such as sea serpents or mermaids.

On the Hunt-Lenox Globe, one of the oldest terrestrial globes in existence, the notation “HERE BE DRAGONS” appears in Latin near the east coast of Asia. It was a warning that travelers to the region would find themselves beset by unknown dangers of the gravest kind.

Today, Canadians looking for our place in the realms of diplomacy, security and commerce find ourselves in terra incognita, where the dragons may be very real.

Amid the geopolitical upheaval, one of our most pressing priorities is to decide what role we want to play—in diplomacy, security and business—in the global community as it is today. It’s an issue on which none of our political parties has presented a coherent vision, where the questions are confusing and the stakes are high, and where the pace of events leaves little time for thoughtful study.

The challenge of finding our way in this new world is further complicated by a growing distrust of institutions and leaders throughout much of the Western world.

We all view how the world is progressing based on our own experiences. In my case, I received a close-up view of the world during my time in the federal cabinet in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Three characteristics of this period stand out in particular. First, it was a time of tremendous hope. We watched as hundreds of millions of people moved from dictatorship into freedom. This progress was most evident with the collapse of Soviet Communism, but it extended to much of the world.

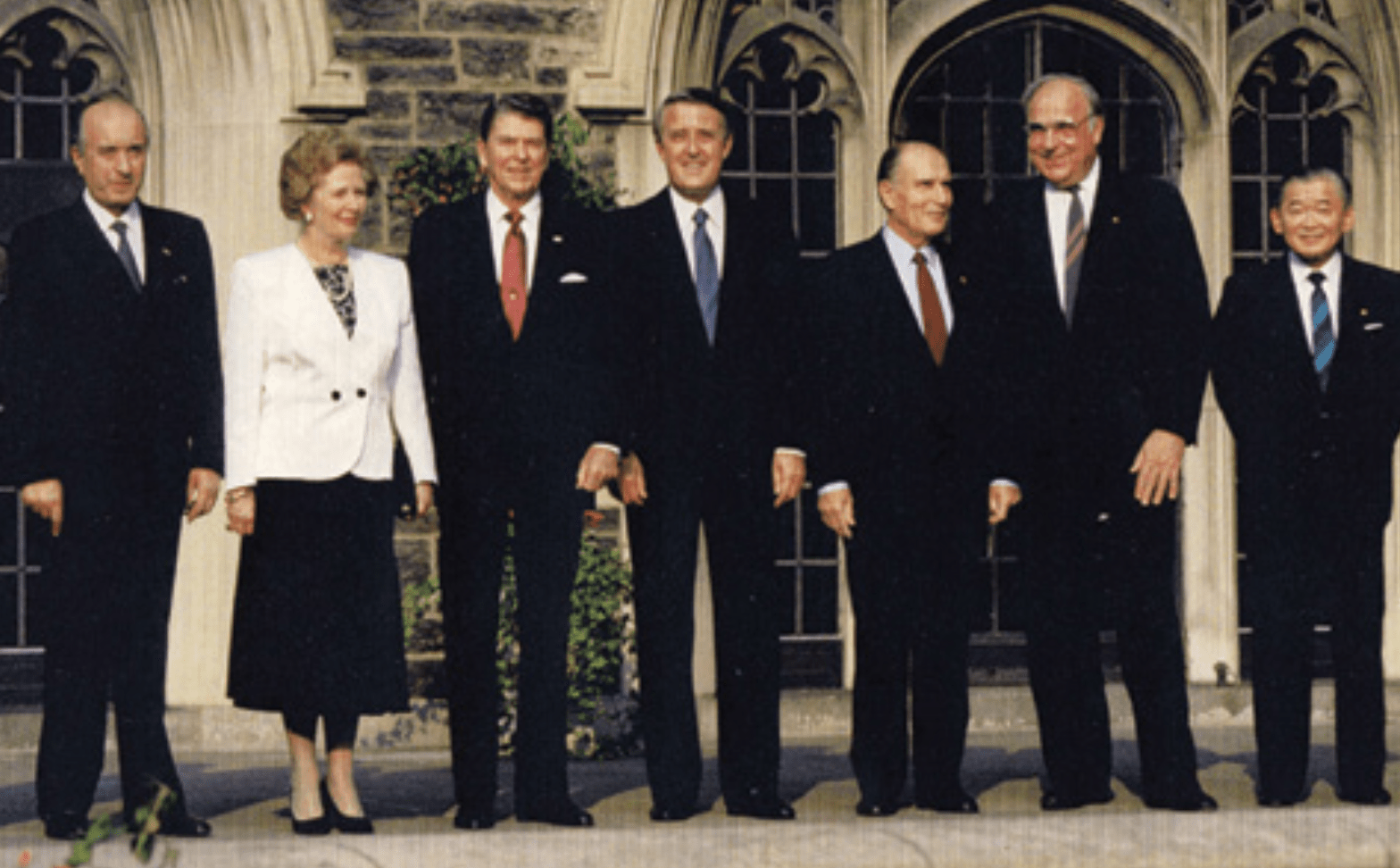

Second, Canada enjoyed a seat at the table when the most critical decisions were being made in the G7, NATO, NORAD and on the Security Council of the United Nations. This was partly a legacy from our role in World War II and the subsequent post-war reconstruction, but it also reflected the personal relationships that existed between Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and other key heads of government.

The third difference between that period and today was the sense that the leaders were bigger than the issues. When Reagan, Thatcher, Kohl, Mitterrand and Mulroney met, we were confident that global issues would be resolved. In contrast, when the G7 met in Biarritz late last August, success was defined by the fact that the talks did not break down.

Many of our instruments for global governance and security, including the Bretton Woods institutions, NATO and the United Nations Security Council, are products of the post-World War II era. Their structures exclude many of the players that have risen to new prominence in the intervening years, and more recent institutions like the G20 and the World Trade Organization appear lost in a cacophony of competing voices.

Compounding this problem is the U.S. shift away from multilateralism to a grumpy, mercantilist nativism that prefers having clients to allies. The Trump administration’s trade, security and diplomatic policies have cost its friends while empowering its strongest opponents. As the United States pulls back from its traditional allies, it has also turned against some of its own creations, including the WTO.

If job one on the international scene is to define Canada’s role in the world, it starts in Washington, where Canada faces a sometimes hostile administration.

It’s tempting to assume that this will be a one-term aberration and that things will return to normal after either the 2020 or 2024 presidential elections, but we simply no longer have the luxury of quiet complacency that all will be for the best. Instead, we need to lessen our vulnerability to capricious actions by reducing our economic and diplomatic dependence on the U.S.

A final difference from how we expected the world to evolve 30 years ago is the challenge posed to Western liberal values by competing systems of politics and ideology. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Soviet Communism seemed to symbolize precisely that. Nor did it seem unreasonable to think that bringing China into international organizations and encouraging partnerships with its government would advance human rights in that country.

The events of the last three decades show that, while others may want to have what we have, they may well not want to be what we are. The forces that explicitly reject the basic tenets of Western society—democracy, equality, human rights, individualism, tolerance and diversity—present a credible and, to many, attractive alternative to a democracy they consider undisciplined, divided and weak.

So, where do these developments leave us? What are our options, and what should be our priorities? And on what assumptions should we plan a new role for Canada in global affairs? Here is my assessment.

First, Canada is more alone today in the world than it has been at any previous period in our lifetimes. While the United States will continue to be our most important partner, customer and ally, we can no longer take our relationship for granted.

Second, while our role as a middle-power country gives us a platform, it provides no guarantees that we can get our way in international affairs, particularly when we are dealing with much larger players. As a result, Canada’s interest is ensuring that other countries play by the rules. That is why multilateral institutions like NATO, the UN and the World Trade Organization are essential to us.

We will need to fight for a seat at the table when decisions are being made and demonstrate why we deserve it, as Canada’s uphill struggle to win election to the UN Security Council demonstrates. A starting point would be to give a clear explanation of what we hope to achieve if we are accepted.

Third, our actions need to be guided by a sense of modesty or, at least, by realism. We should speak clearly and work tirelessly in defence of human rights throughout the world, but we also need to engage all countries, including those whose systems of government we find oppressive. We must do so with clear eyes, with a focused view of Canada’s interests and with an understanding that the game won’t be won in the first period.

Fourth, we need allies among countries that share our values and interests and that are not so large that they believe they can go it alone, such as the countries of the European Union and Scandinavia, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico and South Korea.

I want to be very clear here. While the challenge of asserting Canada’s leadership is more complex and difficult than in the past, we can exercise global influence well beyond what the size of our population or our GDP would suggest if we have a coherent view of what we want and a strategy to get us there.

Finally, we need to rebuild a multi-partisan consensus on our international role. In recent years, consensus has frayed and Parliament is increasingly dividing along partisan lines on issues, including how to manage our relationships with the world’s most powerful countries, the amount and nature of our international aid, our role in the UN and whether the purpose of our trade agreements should be to permit Canadian businesses to compete or to promote a multiplicity of social policy goals.

But however the government manages the process, what should be the basis of our strategy? In my view, Canada’s diplomatic role should be what we have historically done very well: to engage, to convene, to present innovative ideas and to build consensus.

Our aspirations need to reflect our capabilities. We do not have unlimited resources and friends, and Canadians need to know why our international engagement is so important here at home. We need to pick the areas where our international involvement advances Canadian interests and explain to Canadians how what we do benefits them.

On this latter point, we should not be shy about promoting Canada’s commercial interests. Canada, as a trade-dependent nation, should act like one.

Our success in international markets requires a rules-based global trading system overseen by a reformed and renewed World Trade Organization, in addition to our bilateral trade agreements and membership in other global standard-setting bodies.

Our NAFTA, CETA and CPTPP memberships give us privileged access to key international markets. No doubt we should be looking at others as well, but any new negotiations should be based on commercial considerations, not photo-ops. We need to focus on where bold leadership can achieve the greatest benefit for Canada and resolve barriers to our companies’ market access in areas like agriculture, industrial subsidies and digital trade. And while trade agreements open doors into international markets, we need to concentrate much more on how to get Canadian businesses through them.

Businesses can also play a key role by promoting Canadian objectives in fora like the G7, G20, and OECD. Each of these groups has business advisory bodies that provide a platform for Canadian companies. The government should work closely with the private sector to coordinate Canadian priorities rather than having us row in separate directions.

As the threat posed by climate change demonstrates, the problems Canada and the world face today are daunting, and principled, visionary leaders are in short supply. Yet, this is far from the first time that we have had to confront threats that seemed existential. In the last century alone, we were forced to deal with a global depression, pandemics, two world wars, and a protracted struggle between nuclear-armed superpowers with the capacity to destroy every living organism on Earth.

History provides no guarantees of our future success, but it does demonstrate that the gravest challenges often produce the most transformative leaders.

For all of our problems, we Canadians remain the most fortunate people on the planet. The challenge now is to ensure that our leaders have the vision, the principle and the strength of purpose to achieve our potential both here at home and in our relations with the rest of the world.

Perrin Beatty, President and CEO of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, was a minister in the Mulroney government. Adapted from the 2019 Thomas d’Aquino Lecture on Leadership last November 6 at the National Gallery of Canada.