Seeing Russia, and the Arctic, from Helsinki and Tallinn

The customary capping of Havis Amanda on Vappu, or May Day, in Helsinki/University of Helsinki

The customary capping of Havis Amanda on Vappu, or May Day, in Helsinki/University of Helsinki

Colin Robertson

July 2, 2023

It’s been my experience that the best way to adapt to a new time zone is to get outside, walk for as long as possible in daylight, then try to stay up until the local bedtime.

But from Ottawa, it’s at least two connections – for us Montreal and Copenhagen – meaning travel time of at least 14 hours, before you arrive in Helsinki. So, it was not without some grumbling from those who wanted a nap that we explored Helsinki’s leafy Esplanade with its shops, bars, restaurants, Market Square and the majestic City Hall that adorn the heart of Finland’s capital.

It seemed that most of the city’s 631,000 citizens were out enjoying the warm June weather and — because Helsinki lies at 60 degrees north latitude (about the same as Whitehorse) — the daily twenty hours of sunshine. Sampling the reindeer sausage met with a mixed response: how could one eat Rudolph? Instead, we enjoyed the ubiquitous salmon soup.

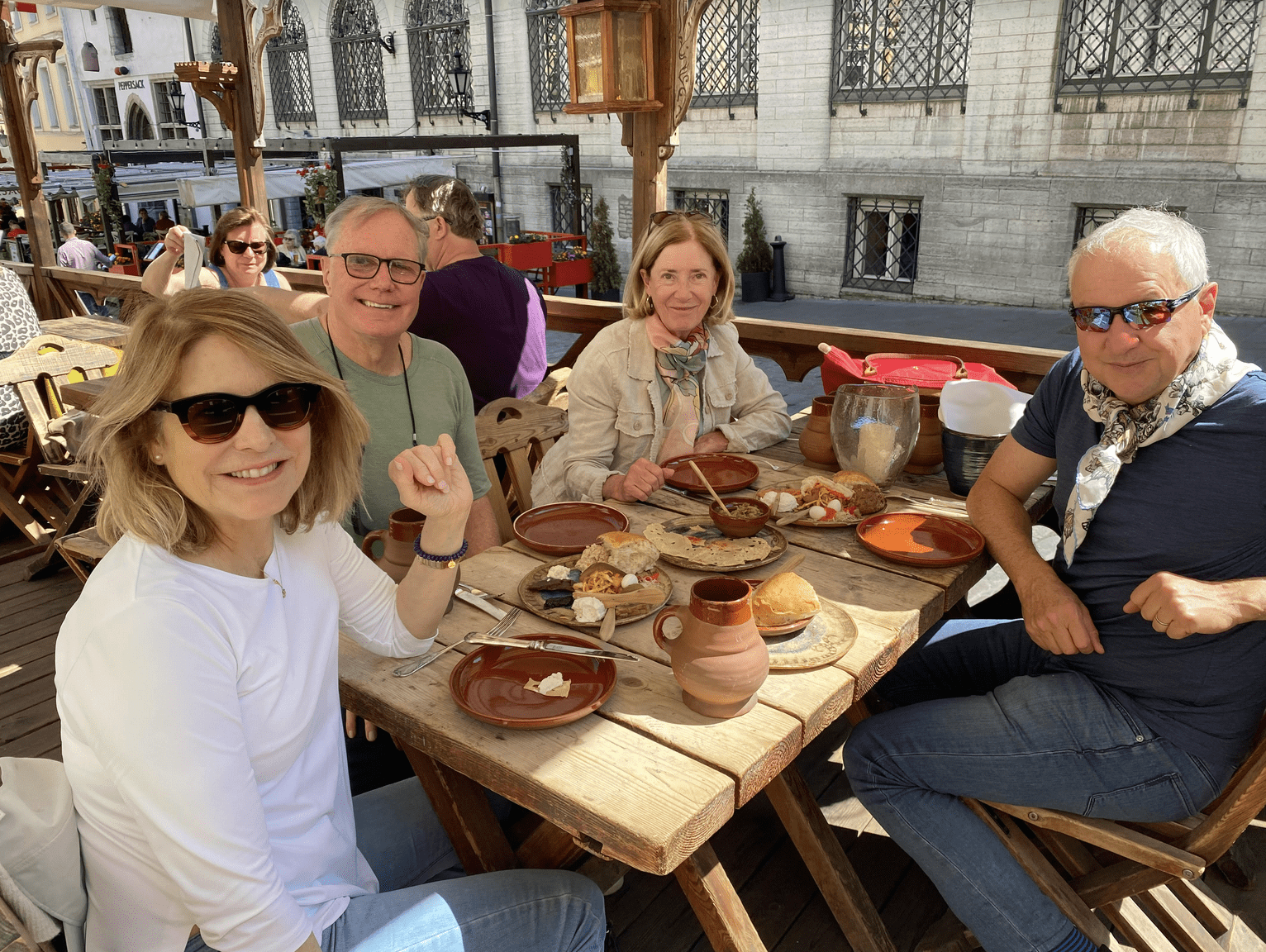

L to R, Dominique Lanctôt, Colin Robertson, Maureen Boyd and Paul Setlakwe in Old Town, Tallinn.

L to R, Dominique Lanctôt, Colin Robertson, Maureen Boyd and Paul Setlakwe in Old Town, Tallinn.

Flanked on either side by linden trees, the Esplanade runs parallel to the old harbour. Revived by the crowds and sunshine, we took a boat tour of the harbour, which also features the Suomenlinna sea fortress. Built in the mid-18th century during the Swedish era, the fortress is now a UNESCO World Heritage site and popular picnic spot for day-trippers.

Leaving our harbour cruise, we were met by a parade down the Esplanade — costumes, balloons, confetti, glitter, paper streamers, noise, music and dance. Such festivities are common during the short Finnish summer, which begins with ‘Vappu’, celebrated May 1st to mark the arrival of spring.

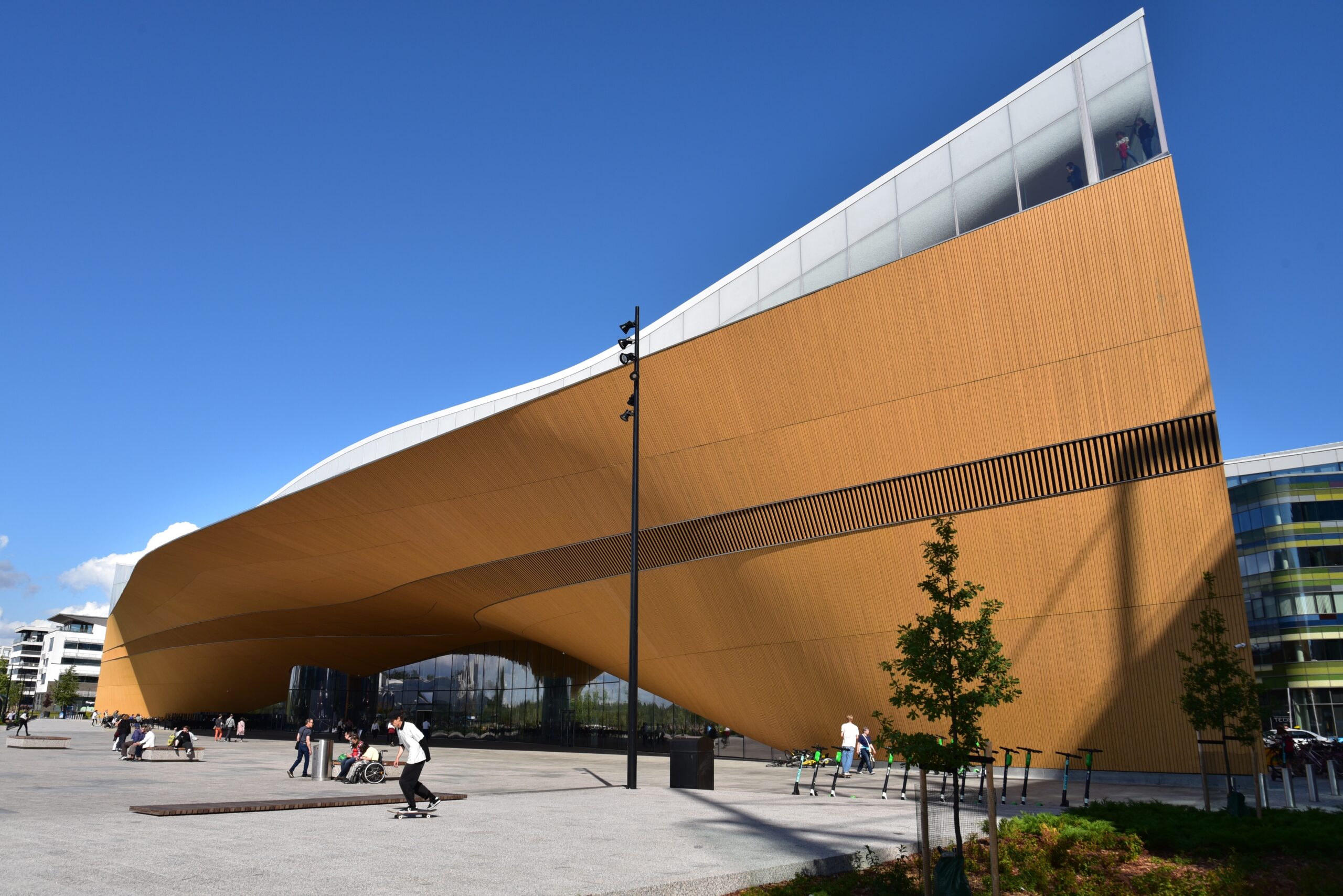

In a nation where 5.5m million people borrow close to 68m books a year from public libraries, Oodi, (“ode” in English, as in an ode to literacy) Helsinki’s new library, is the model of what a contemporary community centre should be: accessible, light, open with studios and workshops and a complement to thecultural and media hub formed by Helsinki Music Centre, Finlandia Hall, Sanoma House and the Museum of Contemporary Art, all across the street from the Finnish Parliament. Ottawa would be the better if we simply cloned Oodi.

Helsinki’s new national library, the Oodi/Wikimedia-Bahnfrend

Helsinki’s new national library, the Oodi/Wikimedia-Bahnfrend

Helsinki is also a global design center, with two museums and a design district that includes its iconic Marimekko brand.

We enjoyed the hospitality of our ambassador, Jeanette Stovel, at a reception in the new Canadian Residence, walking distance from Esplanade. The spacious apartment replaces the garret-like quarters her predecessors endured after the Harper era sell-off of official residences. As Jean Chretien aptly observed “you don’t do diplomacy out of a basement”.

The Finns are regularly judged — six years in a row now — the ‘happiest’ people in the world. Researchers believe that Finland’s top ranking is due to the quality of institutions that boast rule of law, freedom and low corruption, its welfare benefits that provide education and health care, its trust in institutions and people and Finns’ freedom to make life choices.

The world’s biggest archipelago, three-quarters of Finland’s land is covered by forests and it possesses Europe’s largest lake district. Slightly smaller than Yukon, Finland’s 5.5 million population is just a bit higher than British Columbia’s.

On the recommendation of Finnish friends, we enjoyed day-trips to Porvoo and Tallinn.

The postcard-picturesque Porvoo is an hour from Helsinki if you take the direct double-decker from the main bus station. A late start and poor orienteering meant we rode for an extra half on the local bus.

Colonized by the Swedes in the 13th century, almost a third of Porvoo residents still speak Swedish, Finland’s other official language. Porvoo’s Lutheran Cathedral dates back to medieval times. Finland has two national churches (there is no state church): the Evangelical Lutheran Church, the primary religion representing two thirds of the population, and the one percent who belong to the Finnish Orthodox Church.

We caught the early-morning ferry crossing the Baltic to Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, an 80-km trip that traders have made for centuries. Tallinn and Helsinki were key ports in the Hanseatic League of trading cities that dominated commercial activity in northern and central Europe from the 13th to the 15th century. Free trade continues, as we saw on the return trip, with passengers stocking up on alcohol, including cases and cases of duty free beer.

The 500-year-old cannon tower in Tallinn known as ‘Fat Margaret’/Wikimedia-Hajotthu

The 500-year-old cannon tower in Tallinn known as ‘Fat Margaret’/Wikimedia-Hajotthu

Tallinn is very walkable and we began with the Estonian Maritime Museum located in the 500-year-old Fat Margaret tower (“fat” being the size-ist label for the cannon tower’s rotund shape, “Margaret” for reasons no-one knows for sure) in Tallinn’s Old Town. With its artefacts and diorama, it’s well worth the visit. After a lunch of medieval mead, cheese, salmon, grainy bread and cured meats at Olde Hansa, we joined a free city-provided tour. The guide was excellent, providing a capsule cultural history of Tallinn and Estonia.

Estonian history is a story of occupation by neighbouring Danes, Swedes, Poles, Lithuanians, Russians and Germans. The Treaty of Versailles ending the First World War ushered in two decades of independence (1919-39) before invasion by the Soviets, then Nazi Germany, and then Soviet occupation until 1991. As our guide put it: during the last thousand years Estonia has only enjoyed independence for a half century. This helps explain Estonian commitment to collective security through NATO and its determination to support Ukraine.

Russians, as a result of immigration, now comprise about 1/5 of Estonia’s population, most of whom live in or around Tallinn. It means that Tallinn is a front line in the intelligence war between Europe and Russia. Hybrid warfare, including espionage, cyber-intrusions, disinformation and misinformation, has been daily Russian fare in recent years. Earlier this year, Estonia expelled 21 Russian embassy staffers, saying those remaining diplomats would now match Estonia’s team of eight in Moscow.

Estonia, like its fellow Baltic republics, Lithuania and Latvia, has advocated for military support to Kyiv with a no-compromise approach to negotiating with the Kremlin. Estonia’s 46-year-old prime minister, Kaja Kallas, was re-elected in March vowing to continue the hard line. Her stance has earned her the sobriquet of Eastern Europe’s ‘Margaret Thatcher’. Some see her as a potential successor to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg.

Finland’s National Museum is a good place to grasp its past. Crusade, conquest and colonization meant that from around 1150, Finland was ruled by Sweden and the relationship with Sweden remains close, especially around security and defence, with both nations making applications last May to join NATO. Finland is now a member, with Sweden’s accession still delayed at this writing by Hungarian mischief-making but mostly by Turkey’s continued recalcitrance.

Following the Napoleonic wars, Finland became a principality of Russia (1809) for a century, until it declared independence during the Russian Revolution (1917). Finns turned back Russian invaders in the Winter War (1939-40) but the later campaign (1941-5) resulted in Finland having to pay reparations, cede chunks of its eastern territory to Russia, and resettle several hundred thousand of its citizens displaced by the loss of territory.

The Finns share a 1340 km land border with Russia that helps explain why, with a revanchist Russian neighbour, they decided to exchange neutrality for membership in NATO. Their orientation has always been with the West, and a Finnish ambassador once gently lectured me that ‘Finlandization’, a pejorative term for supineness to a great power in exchange for independence, was a common but false understanding of Finnish foreign policy.

Finland can rapidly mobilize a fighting reserve of 280,000, almost three times the 100,000 in Canada’s Armed Forces. Conscription for men means most Finns have done military service, bringing up the total reserve force to 870,000. There is popular talk of extending conscription to women.

For Finns, the relationship with Russia is existential. During and after my diplomatic career, I found that Nordic diplomats, especially the Finns, possess a clear-eyed perspective on Russia.

While the following observations are not original, they bear repeating.

- The first principle with Russia is to be prepared for sudden turns and developments. It is the common thread of Finnish Russia policy — to be underlined as a first thing, and after the analysis, repeat it in conclusion.

- A key influence on Russian behaviour is its persistent quest for great power status in a system with recognized spheres of influence. Expansionism plays a central role for geopolitical and symbolic reasons.

- Russia views the West as a military threat but it is more than that. For Putin, the West presents an existential threat that is cultural, civilizational, and political. The military-technology and economic advantages possessed by the West feed their feelings of insecurity.

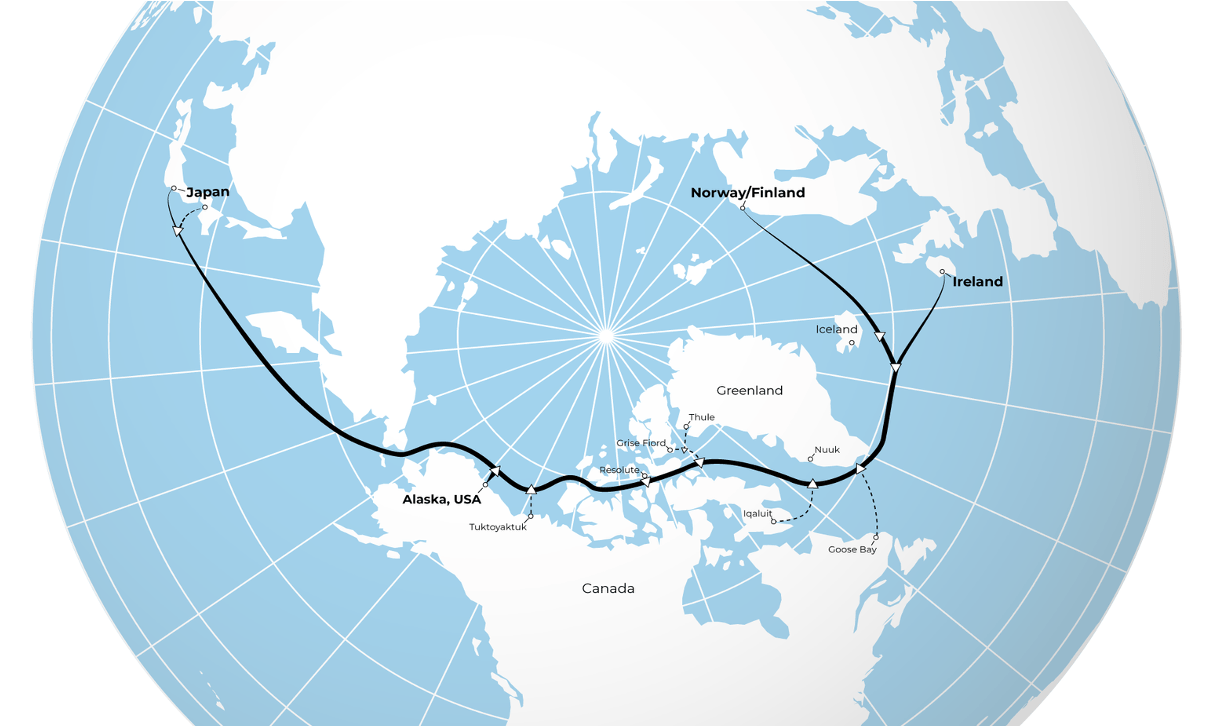

When I asked the Foreign Ministry if they had an ‘ask’ of Canada, they said it was to secure Canadian participation in the Far North Fiber underwater cable system. An attraction for Canada would be its ability to provide connectivity to northern communities.

Running from Finland and around Iceland and Greenland and then through the seabed of Canada’s Northwest Passage to Alaska and then to Japan, it is designed to increase the security and resiliency of digital connectivity. With the backing of Japan, the US, Norway and Iceland, the project is in part a response to increasing Russian intrusions in Nordic watersaround underwater cabling.

The Arctic is also a focus of the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, one of the centres of excellence that cooperate closely with NATO and the EU. Canada is an active member and it is a good investment in practical multilateralism.

It has produced a series of reports on the Arctic, including its most recent, focused specifically on the Canadian Arctic. It warns of vulnerabilities, lack of critical infrastructure and socio-economic inequalities. It also points out that “China, in particular, through hybrid tactics combining military and non-military actions, poses a threat to Canada’s Arctic and could exploit regional vulnerabilities to advance its interests to the detriment of Canada’s own.” Its observations complement those of the recent Canadian Senate report, Arctic Security Under Threat: Urgent needs in a changing geopolitical and environmental landscape.

Canadians like to think of ourselves as a people of the North. It’s a romantic notion although few of us ever venture north of the 60th parallel. Climate, economics and security concerns are rapidly changing this lackadaisical approach.

The Nordic nations, including Finland, take their North seriously. There is much we can learn from their experience. A visit to Helsinki is a good place to begin.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.