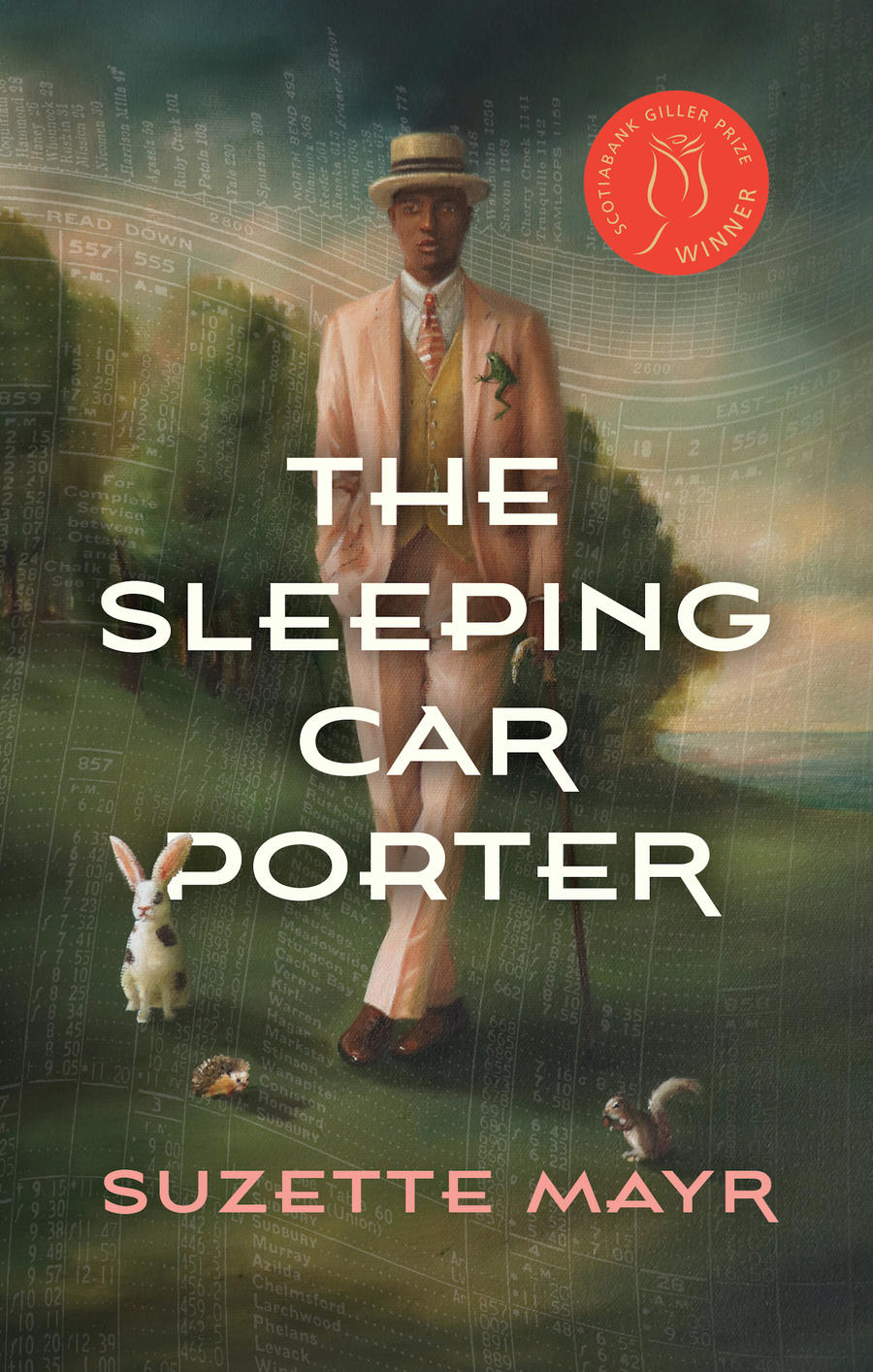

Riding the Magical Rails of The Sleeping Car Porter

By Suzette Mayr

Coach House Books/August 2022

Reviewed by Gray MacDonald

December 20, 2022.

At a moment when so many gaps are being filled with the stories of the less powerful, the less famous, straight, male, and white people who’ve dominated the narratives of history, The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr uses a the eyes of a gay, Black, male, Canadian sleeping car porter to give a fascinating glimpse into a past that’s still relevant. Mayr, University of Calgary professor of and author of 12 books, paints the portrait of a man in a world nearly a century past but at times unnervingly similar to our own. Throw in a dash of magical realism and the adventure is set.

That eponymous porter and lens for this story is R.T. Baxter, though he’s generally addressed by passengers as George. Short for “George’s boys” after George Pullman, joint inventor of the sleeping car model that most of them worked on, and a form of employment-specific racism implying that the railway literally owns him by following the trend of naming Black slaves after their owners.

Navigating the social stratification of Canada in 1929 became increasingly difficult the further away one was from the “default” of straight white man. Baxter’s fear of being outed helps to enforce the racist hegemony: he’s too scared of drawing attention to himself to even consider supporting the other porters’ talk of Black liberation and workers’ rights. He refers to himself internally as a robot, thinking of his body as a machine that belongs to the train: a mental trick he’s adopted in order to survive the dehumanization.

Baxter is roughly a hundred dollars away from quitting, saving up for dentistry school as a path to a better life. The primary impression he leaves is neuroticism, with his penchant for remembering train schedules and habit of thinking of his lost love by his full name. But his very precise, rather detached way of thinking makes his interior monologue an entertaining running commentary about both himself and the world he inhabits. This observational style contributes to the beguiling eccentricity of the novel, which was awarded the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize.

Three things are central to Baxter’s thoughts and therefore the story: teeth, homosexuality, and the train he works on. While these might seem unrelated, in Baxter’s mind they’re enmeshed.

The obsession with teeth is a clever expository device: few details reveal so much about a character so quickly. A person’s teeth can indicate their health, status, history, and general level of affluence. Even in countries with relatively accessible health care, dental care is considered cosmetic and therefore a luxury to maintain; more money = better teeth. So, when discussing class divides, describing the condition of the teeth involved becomes shorthand. Baxter’s interest in teeth, which was initially sparked by a dentistry textbook left in the train’s lost & found, highlights the hierarchy among the characters. This oral fixation (for lack of a better term) is all-encompassing: the man is always thinking about teeth. He recites their names in order to calm his anxiety on shift or to soothe himself to sleep, judges the condition of those in the mouths talking to him, and focuses on them almost clinically when he shares a kiss.

Aside from that obsession, Baxter is mostly preoccupied with suppressing his homosexuality. This becomes more difficult when he comes across a French postcard of two men having an, um, very fun evening together. The postcard is discovered early in the book and haunts our protagonist more than the ghostly figures he begins to glimpse due to lack of sleep. French postcards in general being verboten at the time, being in possession of one featuring a gay couple raises the stakes significantly.

Mayr has picked a fascinating character through which to peer at a moment in history when the status quo was shifting. The prose is clear and distinct, and the two hundred pages fly past like a train along a track.

Currents of queer life flow throughout the book, with every character dealing with identity in some way. One of the passengers claims to be a medium, possessed by the spirit of her brother, and sometimes speaks as a man. Another is a vaudeville performer, the forerunners of drag and an occupation that was, notoriously, a haven for nonconformists. Confronted with people who cross the boundaries of identity and societal role, Baxter reverts to the approach that’s kept him alive so far: keeping his head down and his nose clean.

Finally, the train itself takes on a kind of personality even without supernatural presence. There’s a certain romance to train travel; as explored by everyone from Hitchcock to Miyazaki. However, the sheer man-hours that go into creating a comfortable travelling experience are staggering, today as a century ago. While Baxter’s situation is structurally racialized, long shifts back to back to the point where employees hallucinate or lose consciousness are no more a thing of the past than the racism that enforces his assigned role aboard the train.

And yet, there’s something about stepping into a room in one location and stepping out of it in another that always seems like magic to our ape brains. Porter captures this feeling perfectly, describing the train in myriad ways, from a “luxurious prison” to an “opulent string of bedrooms on wheels”. One of the reasons that trains are such a classic setting for murder mysteries is that they create a closed circle in the same way a boat or isolated cottage might. Once it leaves the station, no reasonable humans are getting on or off. When Baxter’s train does come to a forced stop due to a landslide, the small cast of characters we’ve gotten to know is isolated with only each other, perhaps a few ghosts, and Rocky Mountain pines for company.

There’s also a pervasive ambiguity, in classic horror tradition. Baxter is certain that he’s simply hallucinating the shenanigans afoot as the train makes its way westward, but the reader may not agree. Can the self-professed medium actually speak with the dead, or is she simply an incredibly skilled cold-reader and huckster? Is the communication from the dead real, or is it a combination of hallucination and trickery? The book neither takes a side nor tells the reader what to think. Like many great mysteries, it presents evidence for multiple conclusions and then allows readers to decide the answers for themselves.

Mayr has picked a fascinating character through which to peer at a moment in history when the status quo was shifting. The prose is clear and distinct, and the two hundred pages fly past like a train along a track.

Warning to readers: I’m not sure whether to attribute this to suggestibility or guilt, but marinating in Baxter’s dental observations has had me brushing better. Sometimes when you finish a book, you feel like your brain is thanking you. By the time you hit the final sentence of The Sleeping Car Porter, it’ll feel like your teeth are as well.

Gray MacDonald is social media editor for Policy magazine.