Responding to the Unprecedented: The Politics of the Emergencies Act

When a siege of downtown Ottawa by an obstructive invasion of 18-wheelers and performative, viral chaos actors created a political flashpoint prompting federal politicians to take sides, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau took the side of peace, order and good government by invoking the Emergencies Act. Longtime Liberal strategist John Delacourt breaks down the politics of that decision.

John Delacourt

If, in February of 2020, in the initial discussions around COVID preparedness our governments were having, you sketched out a scenario on Parliament Hill similar to what happened over these last few weeks, you’d be considered a fantasist with a particular bent for dystopic spectacle. To imagine pundits arguing the crucial, Charter-specific differences between the Emergencies Act and its predecessor, the War Measures Act, at this stage in the story, violates our conventional understanding of a narrative arc and plot points that propel the resolution of conflict.

Civil unrest should be a first act thing, especially in a country like Canada. We should be well on our way to our new-normal happy ending. This pandemic movie needs new writers – if only to red pencil those hot tub scenes on Wellington Street, just a few steps away from the Prime Minister’s Office. We can’t un-see what has happened.

And history is supposed to be some kind of guide for pattern recognition, and to provide us with lessons learned. For many of the commentariat, to write about the coming of the convoy was to look for ways in which we can read the significance of the occupation of Parliament Hill by comparing it with the insurrection in Washington on January 6th of last year, or the Chilean truckers’ protest in 1972, which led to the coup that brought down the Allende government. Yet as thought-provoking as the comparisons might be, no such historical example quite rhymes with the last few weeks in Ottawa.

Only one narrative thread resonated the strongest for our understanding of the protest’s ultimate impact: the follow-the-money story. Once the media and the government started looking into the sources of funding for the occupation of Parliament Hill, the support from sources in the US was not just incidental, it was foundational.

This new toxic form of protest – anti-democracy, seemingly illiterate if not profoundly narcissistic in its understanding of rights and freedoms – takes its place among a cluster of problems that are looking a lot like horsemen of global economic apocalypse, if not global conflict. Like the climate change emergencies, the supply chain logjams, the looming threat of term inflation and now the crisis in Ukraine, these developments require multilateral triaging first and foremost, and Justin Trudeau, like Joe Biden or his other colleagues in the G7, has limited scope and resources to address these on his own.

This is all necessary context to assert the new principle of governing during the pandemic years: inevitably each crisis lands on Trudeau’s doorstep. But rarely has the leader himself been such a lightning rod.

The crisis was slowly moving in this direction as the protesters turned Wellington Street into the site of a strange anarchic carnival, complete with a colourful cast of enablers, neo-Nazis, fellow travelers and useful idiots within Parliament. Those suffering through this in Ottawa kept having to redraw the lines in the sand. The first was the complacency/complicity of the Ottawa Police Services, the second was the fecklessness of the local and provincial governments. Notably, Doug Ford’s Ontario government would not even attend crisis meetings for all three levels of government, considering them “a waste of time.” Like the unhinged demonization of Trudeau that animated most of the demonstrators’ spit-flecked fervor, there was one implicit message for the federal government from the very beginning – you’re going to have to deal with this, we don’t care if it’s not your fault.

From this vantage point, the desire for Trudeau to strike a defiant pose early on in this crisis and to play into the narrative of the protesters was voiced as strongly among Liberals – especially those of the Chrétien vintage – as it was among those who would never vote for the Prime Minister. Better than the Shawinigan handshake, the invocation of the Emergencies Act was spoken of as the ultimate tribute to his father’s “just watch me” moment during the FLQ Crisis on Parliament Hill. The implications of the Act itself – that it was intended for the “preservation of the sovereignty, security and territorial integrity of the state” – didn’t seem to matter as much as the opportunity for the boomer heritage minute.

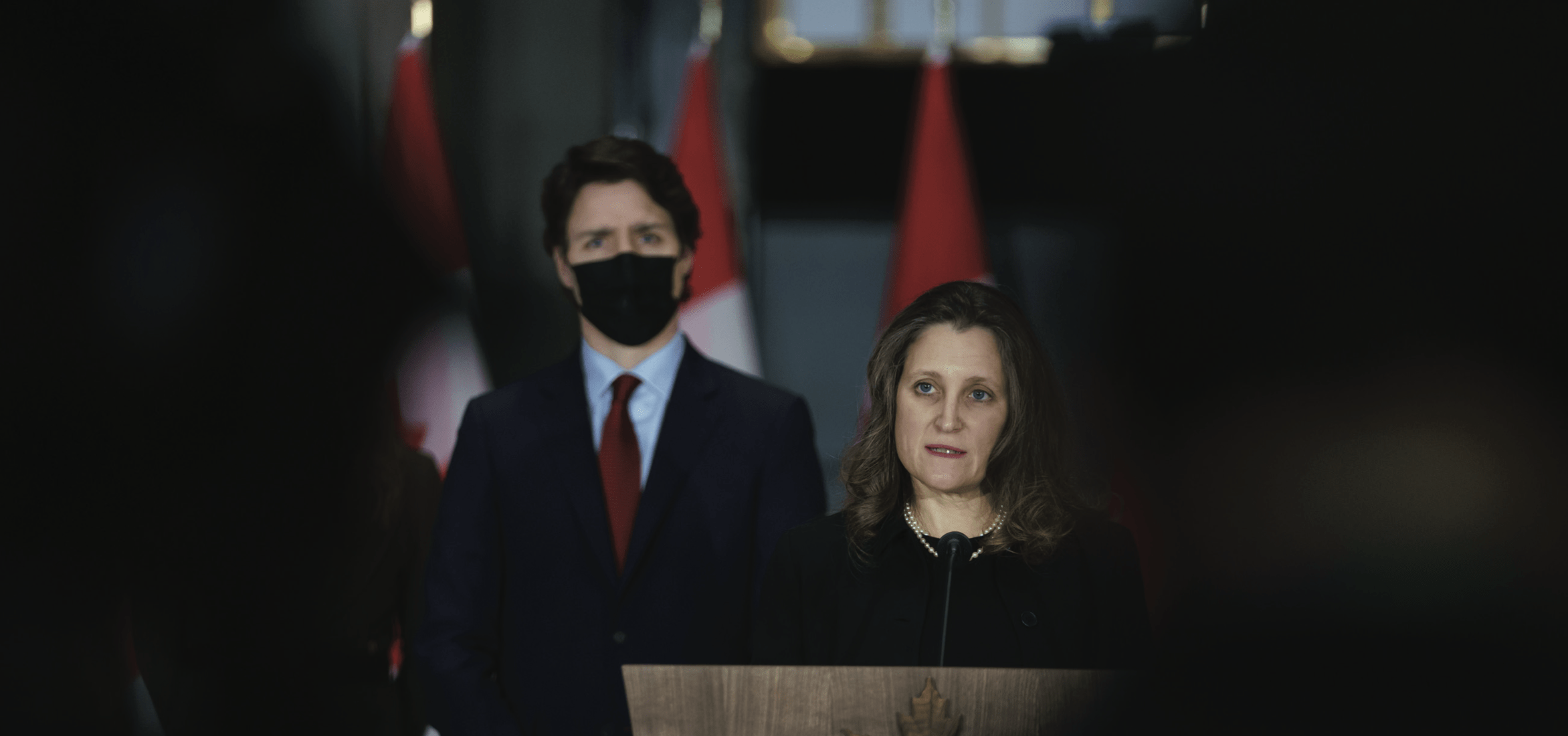

It mattered to the Prime Minister – and to his key ministers on this file: Marco Mendicino, Bill Blair and, of course, Chrystia Freeland. To presume that Trudeau was not acutely aware of how he would be caricatured is, I would suggest, a flawed underestimation of his own political nous. He and his closest advisors knew that a clip of him invoking the Act might provide the endorphin rush on Twitter or Facebook for a legion of armchair quarterbacks, but then the damned bill would have to be debated and justified in, you know, Parliament. As Conservative Michael Chong proved, in a speech so well written it must have eluded – and angered – Candice Bergen’s OLO, you could both roundly condemn all that had gone on just steps from the Chamber and still not vote for the Act’s invocation on the basis of its proportionality and it being demonstrably justified.

And it was not like Mendicino or Blair had limited experience with such questions either. Mendicino’s decade as a federal prosecutor had more than familiarized him with the rights of domestic terrorists when he took on the case against the Toronto 18. And Blair, as chief of the Toronto Police Services, had his own brush with the perils of federal overreach when he was compelled to defer to his old boss, Julian Fantino, and his comradely penchant for talking up riot prevention tactics with the RCMP during the planning for the G20 Summit in Toronto. We all saw how that went for him.

However, if there had to be any hinge moment that allayed such hard-won doubts about the invocation, it might have been owing to another insight Blair brought to the table from his former job. During the succession planning phase of Blair’s time as police chief in Toronto, there were two promising candidates contending for the position: Mark Saunders, who eventually took on the chief’s role, and a bright up-and-comer, rumoured to be Blair’s preferred choice, named Peter Sloly. Just a short time before Sloly announced his resignation as Ottawa’s chief during the occupation, Blair called the lack of effective policing on Parliament Hill “inexplicable.” You can be assured there were many private conversations, many attempts at explaining from Sloly, before that damning judgment was made.

Blair’s exasperation might still not have been enough, however, without one other voice of support for the Act at the table. As it’s now evident with Freeland’s working the phones to shut down Vladimir Putin’s money taps, the finance minister’s own sharp eye on sources of funding for illegal activities was honed from her time as a reporter, not least in Moscow itself as bureau chief for the Financial Times. She had early exposure to destabilization tactics and she is clearly unafraid to go after them with the zeal and diligence required to shut them down.

The irony now is that the Act was revoked prior to its making its way through Parliament. Yet it managed to achieve two objectives for Trudeau’s Liberals: it provided the necessary leverage of authority to address the absence of effective policing and it sent a message to the dark forces of democracy destabilization that their sources of funding can be cut off at any time.

So, a show of disciplined force on the ground and a surgical asseveration of funding. The prime motivators for the invocation of the Emergencies Act now look to be the decisive factors for defence in the larger conflict now playing out on the world stage, and we can only hope they ultimately prove as effective.

Contributing Writer John Delacourt, Vice President and Group Leader of Hill and Knowlton Public Affairs in Ottawa, is a former director of the Liberal research bureau. He is also the author

of three novels.