Red (Sea) Alert

By Douglas Porter

January 12, 2024

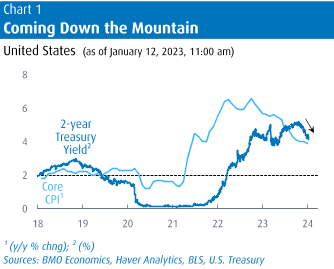

After stumbling out of the gate to start 2024, markets revved back up this week on the growing conviction of near-term Fed rate cuts. Never mind that a variety of Fed officials have urged patience, with some directly stating that March is “too soon” for potential cuts. Never mind that the December CPI landed on the high end of expectations with meaty 0.3% readings on both headline and core. Never mind that financial conditions have already loosened to the extent that—by some measures—they are now actually a tailwind to growth (with even crypto on a tear, until Friday). And never mind that oil prices and some shipping rates have ratcheted up on the US/UK strikes against the Houthis in Yemen. Only know that 2-year Treasury yields have cascaded to their lowest level since last spring (when the regional banking crisis was raging). At around 4.15%, they are now down more than 100 bps from the peak of just three months ago.

The steep drop in 2-year yields directly reflects the market’s strong view that the Fed will begin rate cuts early, and often. As of writing, the market has more than an 80% chance of a Fed rate cut by the March 20 meeting, and a total of more than 160 bps of cuts for all of 2024. Offering up protestations that this pricing is too aggressive has a King Canute feel. (Aside: According to credible sources (Wiki), Canute has been misrepresented—he knew full well the tide could not be stopped, and instead used it as a prop to show the power of God. But I truly digress.) Even so, here are three:

1) The U.S. economy remains incredibly resilient. While it was a light week for economic data, there was a bounce in consumer credit (up $23.8 billion in November), a better trade deficit for the same month, a pick-up in small business sentiment, and another very low reading on initial jobless claims (202,000). And while growth has cooled from the sizzling 4.9% clip in Q3, the Atlanta Fed GDP Nowcast is still pointing to 2%+ growth in Q4. The most recent Blue Chip consensus has been boosted three ticks to 1.6% GDP growth for all of 2024 (close to our 1.5% call), not far from the economy’s long-term potential. The main point is that there is no urgency for rate relief.

2) Inflation remains sticky. The small bounce in core CPI now has the 3-, 6- and 12-month trends locked in a 3%-to-4% range, with so-called supercore even firmer. True, the PPI was much milder, with core prices flat last month, more than washing away any bad taste from the CPI (at least in the market’s view). But note that the inflation pressure is now entirely a services story—core goods prices in the CPI are basically unchanged in the past year, so a flat PPI should be little surprise. Meantime, core services prices have actually been ticking back up in recent months. And recall that last week’s jobs report revealed a small back-up in average hourly earnings, which seem to be steadying at just above a 4% pace.

3) Financial conditions have already loosened mightily. For much of the Fall, Fed officials often approvingly suggested that tighter financial conditions were doing some of the work for the Fed—well, those tighter conditions are now on strike. The Dow is at an all-time high, the S&P 500 is currently toying with one, and long-term mortgage rates are down 110 bps from the peak to levels first hit in September 2022 (when the Fed funds rate was more than 200 bps lower than now). And while it feels almost unseemly bringing crypto into the picture, the fiery resurgence of bitcoin hardly suggests that financial conditions are restrictive.

Pulling these strands together, we would again assert that market pricing is overly aggressive. Having said that, we readily recognize that our call—of a July start and 100 bps of cuts this year—is cautious, and the risks are heavily skewed to faster/deeper chops. And, in the interest of fairness, would offer up a reasonable counterpoint to defend market pricing. First, and perhaps the best argument, is that while Fed policy needs to stay restrictive for some time, it need not be this restrictive. (The overnight target is more than 200 bps north of underlying inflation.) Even with rate cuts of 100 bps or more, it could be reasonably asserted that policy would still be tight.

Second, while core CPI is sticky, the Fed’s main inflation gauge—the core PCE deflator—is much more relaxed. Recall that this measure rose just 0.1% in November, clipping the 12-month trend to 3.2% and the six-month pace to just 1.9%. Richmond Fed President Barkin, a voter this year and of the mildly hawkish persuasion, pointed out that this means that inflation has now been at the Fed’s target over a six-month period. Just a year ago, this measure of inflation was still cruising along at a 5%+ pace. That is real progress. The December reading on the PCE deflator is due two weeks hence (Jan. 26), and it looms large.

The annual gabfest/chinwag of Canadian bank chief economists was held Thursday morning in downtown Toronto before 1,200 of our closest friends. I’ve left it for an afterthought this time, as there was an amazing (unnerving?) similarity in our views and forecasts this year. Most are expecting the economy to struggle to grow in 2024 (our 0.5% call on GDP is close to consensus), with one openly talking about a recession. There’s no disagreement that the Bank of Canada will reverse course this year, although our call of 100 bps of trims (starting in June) may be a bit lighter than some others. There was much hand-wringing over rapidly rising government debt costs and a weakened fiscal position—albeit set against an even more challenging U.S. deficit picture ($1.78 trillion in the past 12 months). And most agreed that housing will stay subdued for a while, as the market fully digests past hikes, yet underlying pent-up demand remains robust.

But this year’s conversation was totally dominated by one topic: Canada’s dramatic population surge in the past year. It’s well-known that overall population sprinted higher by 1.25 million y/y in Q4, or up 3.2%, compared with a median rise of just over 1% per year in the prior 50 years. Less publicized is that the adult population rose by 945,000 in the past 12 months, or triple the norm since the 1970s. Even if each one of those additions doubled up, that would require more than 470,000 new housing units (a conservative estimate, to say the least). In stark contrast, the most completions Canada ever hit in a single year was 257,000 (in 1974). As one panelist dryly noted, the math does not add up.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.