Race to the Top — Fixing Childcare Once and for All

We are delighted to host this week-long series of articles by graduate students at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. Look for them here in our Online Analysis section.

Anil Wasif

June 17, 2021

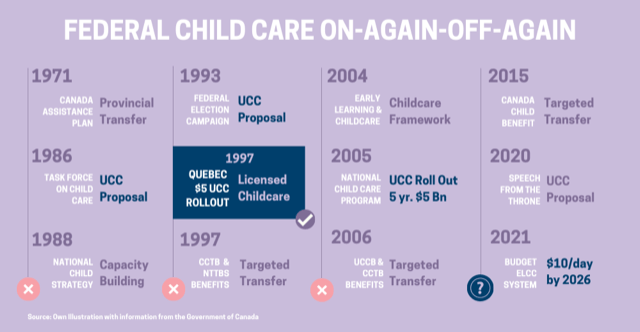

Canada has a problem. Some 50 years, a couple of task forces, and a pandemic later, we are still figuring out what kind of childcare we want. We use words like “equalizer” and “she-covery” yet, when push comes to shove, we shuffle things around.

First, the lexicon. Universal Child Care (UCC) provides every family with free access to childcare. A child benefit promises a top-up for some of our spending on it. They are not one and the same. The former is supposed to come with no strings attached while the latter requires eligibility in one way or other. Before an election, we like to call it UCC and after an election we end up calling it a benefit or transfer. Task forces repeatedly reference Quebec’s directly funded, low-fee system as the one worth scaling up, but the implementation plays out as a change in a box on our tax forms instead.

Honest efforts have been made in the past 50 years but from one working group to another and one prime minister to the next, policies depart from the original concept — resulting in an on-again-off-again focus on an issue so close to our hearts.

The federal budget says it’s different this year. [Re] dubbed the Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care System, it’s presented as the first step to a public system fifty years in the making — perhaps, as universal as we can get, at this moment in time. The commitment is a reduction in expenses to $10 a day by 2026, with at least a 50 percent average free reduction by 2022. The price tag is $30 billion over the next five years. And the plan, (once again) is to create a strategy first — supported by a Federal Secretariat dedicated wholly to the issue and a National Advisory Council that (hopefully!) brings together policy leaders like economist Armine Yalnizyan and YWCA Canada CEO Maya Roy. The good thing is that it’s not a tax and transfer program; the bad thing is that we have tried this twice before.

This brings us to demand and supply. As many argue, historically, the provinces and territories have handled the supply side — childcares, nannies and everything in between — while Ottawa has looked over the demand side, i.e., how much we pay to access care. While the plan has substance and the motive is genuine, it’s important for Ottawa to recognize this notion and diagnose three issues as we prepare to table legislation this fall.

Number one: The pandemic is not over and the bureaucracy has a long list of things to worry about. This includes ensuring that those currently without childcare receive it immediately and it means we have to be careful about how we utilize our resources. Our provincial public servants have worked on this before, and they are more aware of the needs of their citizens than those in Ottawa. Yes, we can always hire the right people with experience and expertise, but we need to be mindful on to ensure the policy lives on when party colours change in government.

Number two: Historically, Ottawa likes to go shopping when our economy re-ignites — often swapping short-term political gain for long- term progress in the process. This time must be different. As we prepare to put the pandemic in our rear-view mirror, our representatives must contemplate the laundry list and prioritize for the long-term. In this regard, the extra time spent thinking could broaden our perspectives — like contemplating energy efficient care facilities for tomorrow’s babies.

… it’s important to think of inclusive solutions that put quality first without displacing those with the experience, talent and skills required to build a legacy system.

Number three: There’s merit in recognizing the people we leave out of the conversation, like the entrepreneurial mothers and carers who run 28 percent of the current system. To this end, less than one-third of Quebec’s suppliers are non-profit organizations, so it’s important to think of inclusive solutions that put quality first without displacing those with the experience, talent and skills required to build a legacy system.

Putting three and three together, Ottawa should set expectations, and let the provinces race to the top. Yes, federal spending on childcare infrastructure needs to happen right here and right now, but we’ll likely be better off if we let the provinces figure out the supply. This year’s provincial budgets provide the perfect opportunity for that. The provinces can leverage the experience and relationships from working with towns, cities and local providers on the issue for the last 50 years, while Ottawa can focus on finding the minimum standards that reconcile quality, affordability and access — ensuring our learnings from Quebec are reflected efficiently throughout.

Fifty years of policy action confirms that childcare is crucial to our economy. The pandemic has made this even more clear, by shifting the conversation away from benefits and transfers. As such, it’s high time for traditional economists to join the conversation and pundits of all stripes to think comprehensively. Everyone depends on someone who depends on childcare.

Anil Wasif is a Senior Consultant with the Ontario Government and a co-founder of BacharLorai. He is currently completing his Master’s degree at the Max Bell School of Public Policy where he serves as the President for the Public Policy Association of Graduate Students (PPAGS).