Putin’s Assault on Common Decency and the Rule of Law Has Backfired

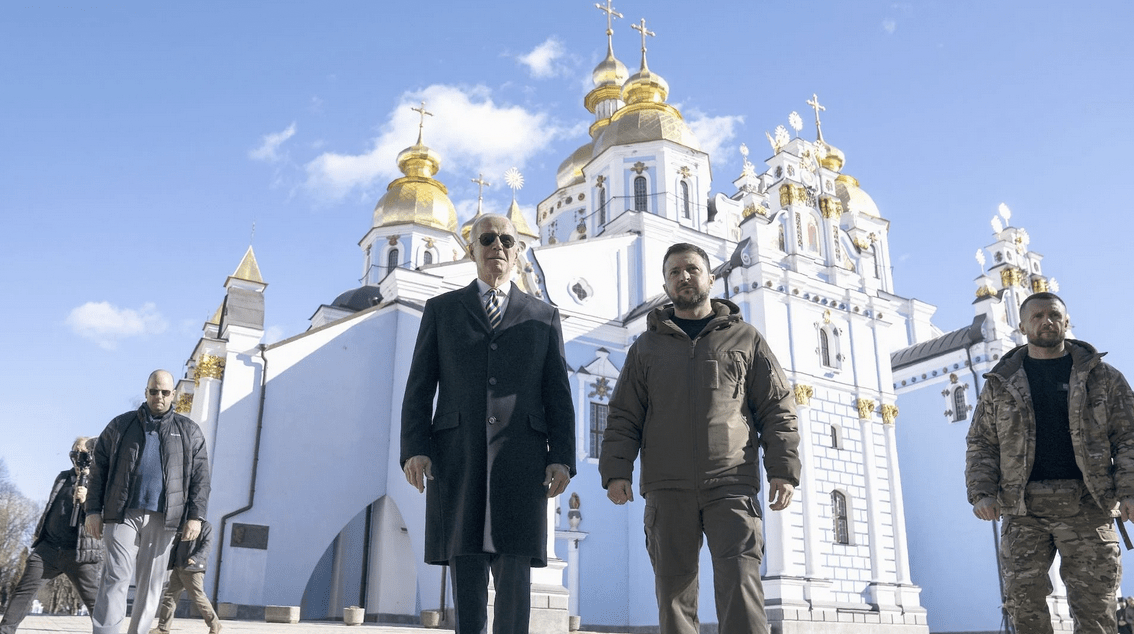

US President Joe Biden on a surprise visit to Kyiv, with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky, February 20th, 2023/AP

US President Joe Biden on a surprise visit to Kyiv, with Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky, February 20th, 2023/AP

Bob Rae

February 20th, 2023

The Russian war on Ukraine has lasted for not just a year, but for centuries. We allowed ourselves to believe that the relatively peaceful breakup of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the recognition of full Ukrainian sovereignty, together with the security guarantees signed by a number of powers, meant that Ukraine’s vulnerability to subjugation had been relegated to history.

How wrong we were. The West’s reaction to Putin’s rise to power was to try to embrace him, to keep him in a G7 expanded to the G8 under Boris Yeltsin, to sign gas deals, to participate in the kleptocratic economy he had created, and to turn the other way when he began wiping Chechnya off the map. That war should have given us more than pause — its sheer brutality should have made us fully understand what we were dealing with.

But the repression and murders of political opponents, the poisoning of foes at home and abroad, all taking place in plain sight, did not wake most people up. Nor, tragically, did Putin’s friendship with dictators around the world, including his continuing role as an arms supplier and military ally to Bashar al-Assad in Syria. The use of chemical weapons in that country was supposed to be a “red line” for the West, but the line disappeared. Rhetorical flourishes replaced military engagement as the preferred response to aggression and crimes against humanity.

The invasion of Crimea in the summer of 2014 was followed swiftly by its annexation. This was met by a resolution of the United Nations General Assembly and more sanctions whose effects were hard to discern. The repression in Crimea was swiftly executed. Russia’s new borders were not recognized, but neither were they effectively challenged. Ukraine’s eastern provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk were attacked, which was met by much organized resistance, and a slow, dirty war of attrition and bombardment was underway.

Underlying all this is Putin’s claim that Ukraine and Russia are really one, that they are not two separate countries or peoples, that the — fabricated by the Kremlin propaganda machine — “nazification” of Ukraine was a plot of the West, and that the “puppet regimes” imposed by the West were not real governments, but illegitimate interlopers who should be swept away. Putin — in a tactic classic among tyrants — targeted the legitimacy and dignity of the other. All his public statements in the last year have reinforced these points, and show that he has learned nothing and forgotten even less.

It was clear from the outset of Putin’s invasion on February 24, 2022 that the “special military mission” was designed to bring Ukraine to its knees in a few days. Its initial targets were not so much in the east as they were in Kyiv and even Lviv. Missiles rained on targets throughout the country, and heavy artillery and tank convoys headed straight for the capital. But Ukrainian resistance was far stronger than anything Putin expected, as was military and other support from the West. While Russia used its veto to stop any response from the UN Security Council, the General Assembly condemned the invasion with an overwhelming majority, and even China decided it could not endorse what Putin had done. Economic sanctions of unprecedented severity followed soon after, and what started as a short, sharp effort at “shock and awe” has become a bitter and brutal flat-out war, with unprecedented battlefield losses for Russia and avoidable suffering on both sides.

The costs of this war in human terms are terrible: an estimated 200,000 Russian troops killed or wounded, with Ukraine enduring about half that number. Because the war has been fought entirely on Ukrainian soil, there have been civilian losses in the tens of thousands, with the forcibly displaced, internally and externally, adding up to more than ten million people. Whole cities have been destroyed, with evidence of crimes against humanity and war crimes being carefully documented by investigators for the International Criminal Court (ICC) and domestic courts in Ukraine. The Russian claim that the war was justified because of clear evidence of genocide being committed by Ukraine against Russian speakers in eastern Ukraine has been categorically rejected by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), and that same court (with the Russian judge agreeing) insisting that Russia has to cease, desist and withdraw its troops.

In addition to legal actions launched at both the ICC and the ICJ, further investigations have been launched by the UN Human Rights Council and European authorities.

Canada acted as an advisor to Ukraine’s government when negotiations were still ongoing, but it was apparent that Moscow wanted nothing less than abject surrender from Ukraine, and direct talks soon stopped. There has been nothing but lies, bluster and bombs from Russia ever since.

At the time of this writing, NATO countries have agreed to increase the firepower of the weaponry being supplied to Ukraine as the Russians begin another ground offensive in the east, and continue with unrelenting missile, drone, and bombing attacks on cities and towns across the country. The war aims of either side have, apparently, not changed: Russia seeks to gain territory in the east (per its unilateral laws of annexation), and to permanently weaken any democratic, Kyiv-based government. Ukraine seeks to regain territories lost since 2014 (including Crimea), accountability for crimes committed, including the crime of aggression, compensation for damages, and admission to both the European Union and NATO.

The military and legal responses are clear; but what of diplomacy? Canada acted as an advisor to Ukraine’s government when negotiations were still ongoing, but it was apparent that Moscow wanted nothing less than abject surrender from Ukraine, and direct talks soon stopped. There has been nothing but lies, bluster and bombs from Russia ever since, and Ukrainians are united in supporting President Zelensky’s determination to fight on in defence of sovereignty and independence. Diplomacy cannot craft solutions out of thin air: it worked well on getting food and fertilizer exports out, but this was only because both parties saw that as being in their mutual interest. Eventually, there will be a settlement, but its terms will depend very much on the strength of will, economics, and the state of public opinion in both countries and in the wider world.

What are the main lessons learned?

– The West underestimated both Putin’s will to conquer and the will of Ukrainians, under President Zelensky’s brilliant leadership, to resist. There is a continuing need to reach a truly unified approach to the conflict. Russia cannot be allowed to win.

– Putin underestimated Zelensky’s will to resist and the West’s will to support Ukraine. He has vastly strengthened NATO unity and therefore NATO power (with Sweden and Finland now in the NATO camp).

– Public opinion in Europe has forced European leaders to toughen up their stance and willingness to supply Ukraine with the weaponry it so clearly needs to meet the Russian attack.

– Sanctions are not a quick solution, but over time can have a powerful effect if effectively targeted and implemented in a co-ordinated way. But they can also have unintended consequences and are a blunt tool.

– The consequential impact of the Russian war of aggression on the global economy, and in particular on the well-being of the poorest countries in the world, are serious. Higher inflation, particularly food and energy costs, and reduced growth throughout the global economy are damaging both living conditions and global solidarity. The war has cost the global economy 2.8 trillion dollars, and added 51 million people to the ranks of the world’s very poorest. Putin’s aggression against Ukraine is in fact a war of aggression against the whole world, free and not. Yet the impact of Russian propaganda and diplomacy in Africa and Asia cannot be underestimated.

– The global legal system is being tested as never before. Many countries, including three Security Council members (Russia, China, and the United States) have not ratified the Rome Statute of 1998 establishing the ICC, and are not subject to its jurisdiction. There is a continuing debate about establishing a special tribunal — as was done with the UN Special Court for Sierra Leone — to deal with the specific crime of aggression, but there is, at this point, no clear consensus how that should be done. Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly has endorsed the concept of a special tribunal, and US Vice President Kamala Harris has said that there is clear evidence of crimes against humanity, but ironically, the US has not ratified the treaty that has created a specific legal process to deal with such crimes.

These last two points are crucially important. Our world suffers badly from a lack of solidarity and effective ways of enforcing common rules amid an ongoing clash between democratic and non-democratic powers that includes unprecedentedly flagrant violations of norms on the part of what were once called “rogue states”. Treaties have been passed that are now more honoured in the breach than the observance as a means of flouting the existing system. At the UN, resolutions are passed but are difficult to enforce. The “enforcers” are not the UN Secretariat but nation states themselves. As a result, the world’s citizens become discouraged and at times this discouragement becomes outrage.

All this leads to another tremendous challenge: how propaganda and disinformation create a world where facts are obscured, where truth is distorted, and where manipulation becomes normalized. It is encouraging that George Orwell’s 1984 has become a bestseller in Russia, but it is important to remember that it is not supposed to be a how-to guide to repression and deception, but rather a grim warning of a world caught in a vice of lies.

And yet, if this is hardly a time for sunny optimism, neither is it a moment for despair. We have to be reminded of these important truths:

-That might does not make right, no matter how loudly or cleverly it takes to the airwaves, or however powerfully its first punch might land.

– That the pursuit of truth and justice are not bromides, but are rather the most important efforts we can make in our pursuit of the common good.

– That conflict is unavoidable in life and the point is not simply to avoid it, but to resolve it in such a way that it is least likely to re-occur.

– That wrong doing should never be rewarded, but should be resisted, and punished by laws consistently applied.

– That nothing is gained from being shortsighted or merely wishful in our thinking.

– That previous generations have fought for freedoms and a better life, and we can do no less in our own time.

In his opening statement to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg on November 21, 1945, Supreme Court Justice and US chief prosecutor Robert Jackson said: “The common sense of mankind demands that law shall not stop with the punishment of petty crimes by little people. It must also reach men who possess themselves of great power and make deliberate and concerted use of it to set in motion evils which leave no home in the world untouched.”

The dream at that time was of a world made whole by a common commitment to justice as a result of terrible conflict. We need to keep that dream alive, even as we face up to how challenging and difficult it can be to achieve. Ukrainian resistance has been at the heart of this struggle from the outset. Article 51 of the United Nations Charter clearly sets out the right of self-defence, which is the principle Ukrainians are upholding. That same article allows other countries to come to Ukraine’s aid as it defends its sovereignty and borders.

We have to find the will, and the means, to bring this conflict to an end. The “off-ramp” is a Russian defeat and a Ukrainian victory, aided and assisted by countries committed to the defence of the rule of law and the cause of democracy.

Bob Rae is Canada’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.