Preparing for Canada’s Next Normal

After an unprecedented summer of physical distancing and damage assessment, individuals, governments and global stakeholders are moving forward from crisis mode to planning for a post-pandemic reality. What might that inter-woven economic and geopolitical narrative look like? Former BMO Vice Chair Kevin Lynch and former CN and BMO executive Paul Deegan offer some insights.

Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only rocked society today, it is reshaping our tomorrow—rapidly accelerating trends that will define the “next normal” for Canada and the world.

Unless there is another wave of the virus, we are through the shutdown phase, where governments locked down economic and social activity to plank the curve and preserve the health care system. Government fiscal policies during the shutdown have been geared to three things—liquidity, liquidity, and liquidity. The shutdown, while necessary, caused the first-ever recession driven by the services sector, not the goods sector of the economy. Unlike the 2007-2009 period, which affected men particularly hard, especially in construction and manufacturing, the 2020 pandemic recession has disproportionally hit women and visible minority workers in service sector jobs. This, combined with the higher incidence of coronavirus in senior care facilities and among marginalized communities, makes COVID-19 inequality a pressing issue.

Having successfully convinced societies of the imperative to physically distance and shut down normal day-to-day activities, we are now moving into the restart phase—the unlocking of the economy and society. This has been complex and confusing, with contradictory signals from governments and public health experts. Truly, this is the intersection of demand and supply, where firms need to rehire and spend; individuals need to return to work and consume; and trade needs to flow. And all of this is happening with lingering economic and epidemiological uncertainty and very real and very personal health and safety concerns.

While the economic implications of all this are easy to see but difficult to quantify, three things are only too clear. First, the starting point is a global economy in the sharpest recession since the 1930s. Second, the timing and vigour of the recovery will depend on the duration of the pandemic, the state of business and consumer confidence, and the nature of government support and stimulus measures yet to come. Third, the recovery will be uneven and the economy will be scarred with record bankruptcies and lost jobs for some time to come.

While the economic implications of all this are easy to see but difficult to quantify, three things are only too clear. First, the starting point is a global economy in the sharpest recession since the 1930s. Second, the timing and vigour of the recovery will depend on the duration of the pandemic, the state of business and consumer confidence, and the nature of government support and stimulus measures yet to come. Third, the recovery will be uneven and the economy will be scarred with record bankruptcies and lost jobs for some time to come.

And perhaps the most challenging phase is yet to come, the “next normal”, with the complex rebooting of the economies and societies post-pandemic. Few crises change either everything or nothing, and the COVID-19 pandemic will be no different. So, what might the “known unknowns” of lasting change in the next normal include?

A return to the old normal is not in the cards—there will be fundamental and lasting impacts from the pandemic. These aftershocks include: a disruption of global trade and investment patterns; a debt hangover of historic proportions; a fundamental redesign of work and the workplace (including education and the classroom) with highly-intensified digitization; a recognition that a resilient health care system is both a social asset and an economic imperative; and geopolitics on steroids, with impacts touching all countries.

We are witnessing a de-integration of the global economy after decades of increasing globalization. This pivot has been stoked by a rising tide of nationalism and protectionism exemplified by the Trump administration’s tariff wars with China and others, including Canada. It has been fed by strategic competition between the United States and China in key technologies, such as AI and 5G, as well as in geopolitical spheres of influence in Asia and elsewhere. And it was the choked global supply chains during the pandemic that spurred the growing consensus that the world is overly reliant on China—not just for personal protective equipment, but also for pharmaceuticals and their constituent compounds, telecommunications hardware, semiconductors, smart phones, solar panels, wind turbines, lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and other, non-commoditized, manufactured goods.

In the next normal, diversification of supply chains will be the imperative. They will move elsewhere in Asia, with less reliance on China, and there will be a push to re-localize supply chains for critical goods. Digital services trade will be constrained by geopolitical battles over technology standards, taxes, internet rules and cybersecurity protocols.

More rigorous screening of foreign direct investment will emerge from the global recession to protect battered domestic firms, and will be amplified by geopolitical tensions. Lingering coronavirus fears will see declines in people movements, particularly international air travel, international tourism, and international education—a major source of funding for Canadian universities. One consequence of this deglobalization will be a decline in trade flows and foreign direct investment flows, particularly between China and the West.

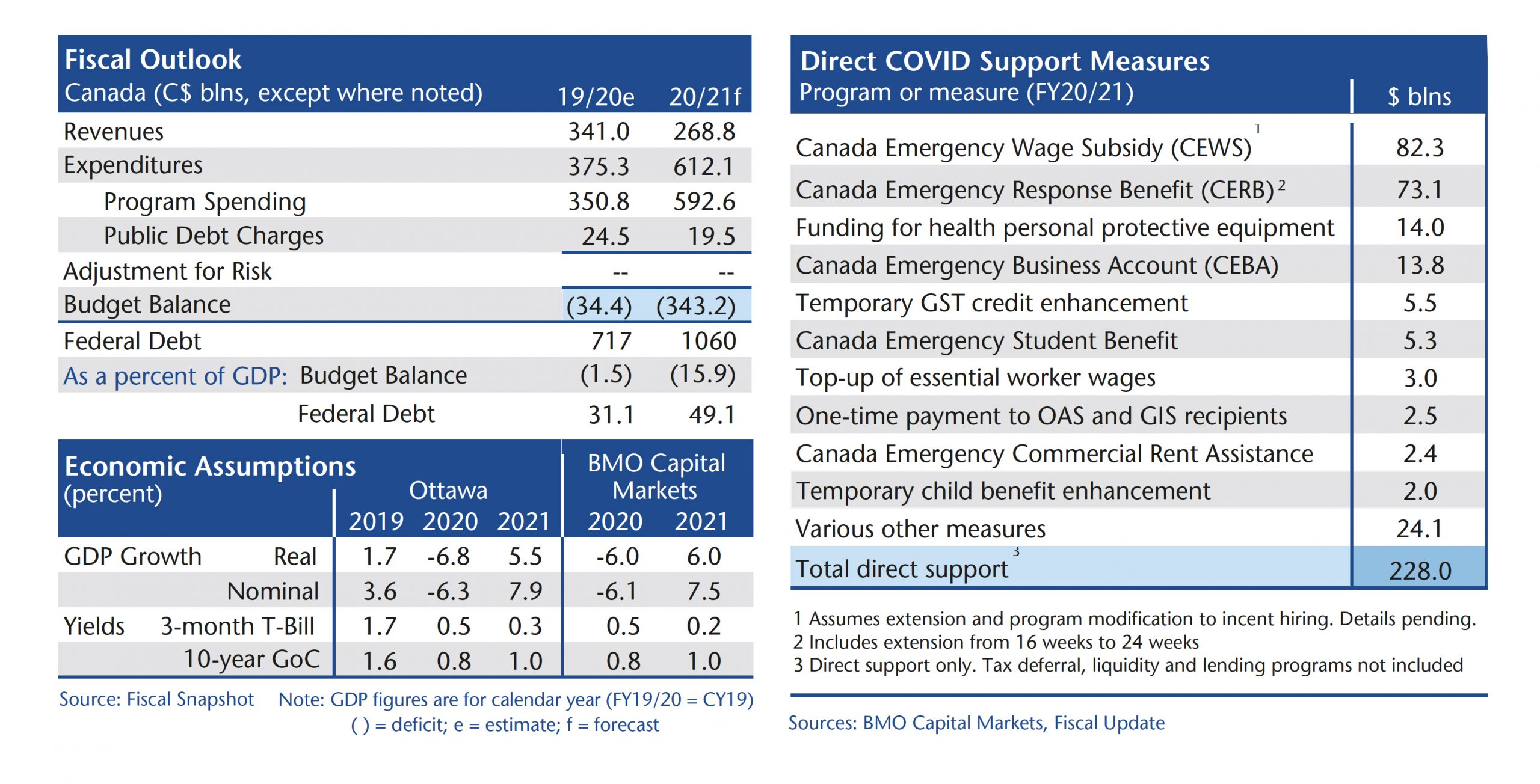

We are in the midst of a debt explosion for governments, as well as corporations and households, and it’s on a scale that Canada has not experienced since the Second World War. In May, we wrote in the Ottawa Citizen that the Canadian federal deficit this year could be—combining automatic stabilizers, supports announced so far, and additional restart stimulus—as high as $300 billion (or than 40 percent of all the net debt accumulated since Confederation). Our estimate turned out to be shy of the $343 billion, forecast by former finance minister Bill Morneau in the July fiscal “snapshot”. To put this year’s deficit in context, it is about the same size as total federal spending in a normal year and represents about 16 percent of GDP. Next year, the deficit could easily exceed another $100 billion, depending on the strength of the recovery and the political willingness of the government to ramp down its massive new spending support programs.

All this will push the federal net debt-to-GDP ratio from 30 percent to 49 percent this year, and our gross debt-to-GDP ratio to over 100 percent, putting at risk Canada’s vaunted debt advantage. Near-zero interest rates make this fiscally affordable as long as they stay near zero. Rising debt-to-GDP ratios make this fiscally stable as long as markets have confidence in the government’s ability to manage the deficit post- pandemic and flatten the debt curve. The next normal’s prospect of low long-term economic growth makes managing this mountain of debt very challenging.

This now trillion dollar plus mountain of public debt, combined with high household debt and nonfinancial corporate sector debt leverage, will require a clear and credible fiscal plan and growth plan to address it. How do we justify interprovincial trade barriers in an era of low growth? What are we going to do to raise Canada’s abysmally low productivity performance? How can we grow the national economy without a regulatory framework that supports both growth in the natural resource sector and improved environmental outcomes? When are we going to upgrade skills training for a digital economy? Where are we going to find new markets for our exports in a world of decoupling trade? Without such a credible growth plan, global markets will place upward pressure on Canadian risk spreads and downward pressure on Canada’s credit rating (Fitch has already taken away our enviable Triple A status) while foreign direct investment will seek opportunities elsewhere. Without a credible fiscal plan, these pressures will only intensify.

The nature of work has changed more in the last six months than it had in the previous 20 years. Employees are working from home en masse and effectively, doctors are doing tele-medicine as a matter of practice, not exception. Consumers are buying online as never before, and stores, by necessity, are finding ways to deliver. Educators have moved out of the classroom and onto Zoom. The workplace has become more virtual, more mobile, less physical, and perhaps less routinized. For work and education, things may never be as they were before.

In the next normal, working from home will become a regular part of the norm, but only part. Businesses will design new hybrid home-and-office work arrangements, create lower density office settings, substitute virtual meetings for travel, platoon employees at the office rather than all-hands-on-deck all the time, and shift to staggered work hours to respond to health concerns around mass public transit and crowded elevators.

Employers will worry about productivity in a work-from-home world, and as a consequence will focus investment and resourcing decisions on digitizing and adapting to a much more digital workforce and a much more digital customer—in both in the B2C (business-to-consumer) and B2B (business-to-business) spaces. They will invest heavily in cloud-based human capital management and sales software to engage employees, customers and prospects. Digital commerce will continue to soar, and traditional brick and mortar retailers will either adapt and innovate, or they will die. Logistics to support online commerce will be a business priority. Merger and acquisition activity will increase as high-quality assets shift from the battered to the strong. Corporate concentration will continue to increase, particularly in the info-tech space.

And, without a vaccine, it is hard to see universities and colleges either attracting large numbers of international students or cramming hundreds upon hundreds of students into lecture halls—both key elements of today’s higher education business model. A shift to more online education, which attempts to address both these risks, puts a very high premium on quality and innovation because, in the absence of physical proximity and exclusivity, a student can attend a university or college anywhere.

This is the third pandemic in just 17 years, and something the public will not soon forget. Indeed, public confidence that we are relatively safe from catching COVID-19 when returning to work and re-engaging in social activities, and that the health care system has the resiliency and surge capacity to deal with another wave of COVID-19 or another virus, will be crucial elements in the vigor and speed of

the recovery.

Social cohesion during the shutdown phase has been high in many countries, and federalism has worked very well in Canada during the shutdown phase. What is clear is that a strong and resilient health care system is both a social asset and an economic imperative in a world threatened by pandemics. And, despite missteps and mixed signals early in the pandemic response, Canada has found its footing and has a structural competitive advantage compared to other countries such as the US with our universal Medicare system and well-connected health care institutions coast-to-coast.

Going forward, we should expect a strong public consensus that Canada needs a best-in-class pandemic response capacity, including early warning systems, stockpiles of critical equipment, skilled pandemic care capacity, facilities to develop and produce antiviral treatments and vaccines, adequate testing and tracking capacity, and surge capacity in ICU beds. Social cohesion and federal-provincial cooperation will be tested in the next normal as difficult policy choices and tough financial constraints apply in government decision making. But pandemics are sadly not a once-off, and neither can be investments in health care response capacity and infrastructure.

Prior to the pandemic, the US, China, and Russia were engaging in the sort of “Big Power” behaviours not seen in decades. The pandemic has vastly reinforced these tensions, particularly between China and the US It has reinvigorated nationalism, in those countries and elsewhere, where blaming “others” is a substitute for taking own accountability. Attacks on the WHO, the failure of the G20 and G7 to coordinate and lead, resistance to new IMF resources to help in the crisis, ignoring international analysis—these all point to the weakness of international cooperation and stand in sharp contrast to how major countries came together to act in the collective interest during the 2008-09 financial meltdown.

In the next normal, we should expect a “back to the future” moment for geopolitics. Rising nationalism, protectionism, de-globalization, and an increasing antipathy to multilateral institutions pose significant risks for mid-sized, open countries like Canada which rely on trade, enforceable rules-of-the-game and a global marketplace. Canada will be caught in the middle of a world where superpowers take an a la carte approach to a rules-based system and the rest of us scramble.

What the failure to secure a seat on the United Nations Security Council demonstrated is not that the world doesn’t like us anymore, but they don’t think they need us as much as they did. They don’t see a Canadian foreign policy to align to, partner with, or support in this new normal of dangerous geopolitics. We are not leading on the Arctic, which is becoming a focal point for US, China and Russia. We are not leading on peacekeeping or peacemaking or development in a world where local tensions have global consequences. We are underinvesting in defence despite it being a collective NATO obligation. We are no longer viewed as having unique relationships with the two superpowers but have not developed new alliances to offset this. In short, we need a clear and compelling foreign policy for the new normal, one that blends national interest with multilateralism and a rules-based system.

COVID-19 has attacked our lives and livelihoods, and it has shaken our economies and the world order. We need to up our leadership game in the world, we need to make difficult domestic economic decisions for the long-term, and we need to move on quickly to shape the next normal for Canada. Prorogation may have been politically motivated, but the upcoming Speech from the Throne provides an opportunity to sketch out a bold plan to build a more prosperous and inclusive Canada. As former prime minister Brian Mulroney stated recently, “Incrementalism builds increments. Bold initiatives build nations.”

Contributing Writer Kevin Lynch was formerly Clerk of the Privy Council and Vice Chair of BMO Financial Group.

Contributing Writer Paul Deegan, CEO of Deegan Public Strategies, was a public affairs executive at BMO Financial Group and CN, and served in the Clinton White House.