Political Capital

By Douglas Porter

July 05, 2024

The U.S. election is exactly four months from today. And following last week’s debate debacle, markets are increasingly turning attention to the vote, and some of the potential policy implications. Up until recently, it seemed that the working assumption for most was that the polls were so tight, and Congress so evenly split, that we were likely looking at some form of gridlock next year. That cozy consensus has been rattled to the core, with the possibility of a Republican sweep gaining some serious ground.

Generally speaking, the recent experience has been that fiscal policy tends to the generous side when a single party is in control in Washington, regardless of the political stripe. Given that we are still dealing with sticky inflation, a budget deficit of nearly 7% of GDP, and record debt/GDP, arguably the last thing the economy needs is a generous fiscal policy stance. And, combined with the accompanying threat of increased tariffs under a new regime, the bond market is on ‘high alert’ for renewed inflation pressures, on top of a potentially meaty supply of new bonds.

Accordingly, the initial market response was to drive long-term yields notably higher. In the first few sessions after the debate, 10-year yields promptly rose 20 bps to nearly 4.5%, even amid generally sluggish economic data and a mild PCE deflator result. But a funny thing happened on the way to the fixed-income storm—yields have since mostly reversed course, taking 10s back down to below 4.3%. First, markets have absorbed the reality that four months is still a long ways off, and much can happen—why, we could probably squeeze in a couple more elections in France in that time span.

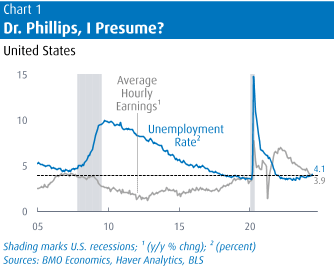

Second, and more importantly for Treasuries, the U.S. economic data have morphed from sluggish to soft. True, payrolls managed to rise a tad above consensus at 206,000 in June. But prior months were revised down heavily, and aggregate hours worked have barely risen over the past three months combined. Moreover, the unemployment rate ticked up again to 4.1%, and is now up half a point from year-ago levels. Wages are accordingly cooling, as Dr. Phillips may have ordered, with average hourly earnings dipping to 3.9% y/y in June—not far from the 2019 average rise of 3.3% (Chart 1).

On top of the back-up in unemployment, both of the ISM reports for June printed soft, with services particularly weak at 48.8. Aside from 2020, that’s the lowest reading for the non-manufacturing index since the deep recession of 2009. This is a relatively young series, as it only dates back to 1997, but it only tends to venture into sub-50 terrain when the economy is seriously struggling. Meantime, the Atlanta Fed’s Nowcast forecast of Q2 GDP has been cut in half to 1.5%, very close to our call (1.6%) and the latest estimate of Q1’s actual outcome (1.4%). We expect the economy to remain on the sub-potential path in the second half of the year, but it’s pretty clear that the risks have tilted to the weaker side in recent weeks. And growing political angst will not help.

Yet, equities remain uniquely able to soar above these political and economic concerns. While Treasuries fret about budget deficits of almost $2 trillion, and a possible inflation relapse, stocks are still looking on the bright side of decent earnings growth and the prospect of Fed rate cuts. And the market is now very much in tune with our call of 25 bp trims in September and December. The S&P 500 managed to push above 5500 for the first time in a holiday-shortened week, grinding out a rise for the 10th time in 12 weeks. One interpretation for why equities have managed to blithely forge higher amid the growing political clouds is that a unified Washington, especially of the one on offer, is definitely not the clear-cut problem for stocks that it may be for bonds.

To quote Mr. Loaf: Two out of three ain’t bad… but is it good enough? We have often cited three main reasons why the Bank of Canada would proceed only very cautiously on the rate cut path. The view was that cuts independent of Fed moves could seriously weaken the Canadian dollar; that cuts could rekindle a smoldering housing market; and, that underlying wage pressures meant the Bank could only go gradually. How are we doing on all three?

The Canadian dollar has been remarkably well behaved in recent weeks, barely budging from the range of $1.36-to-$1.38 (or near 73 cents(US)) since the middle of April. While it did spend most of the first three months of the year softening, it seems to have found stability close to its average level since the start of 2023 (closer to $1.36). The fact that the U.S. dollar itself has more broadly pulled back amid softer U.S. economic data, and prospects of coming Fed rate cuts, has helped stabilize the loonie.

Canada’s housing market remains remarkably sleepy. Early results from the large cities revealed that home sales barely budged in June, even with the BoC rate cut early in the month. The data support the initial view that it was actually sellers who stepped up, not buyers, after the Bank moved. Many of the big cities are still seeing double-digit drops in sales from year-ago levels, big increases in existing inventories, and the market balance shifting in the buyer’s favour. Not surprisingly, prices continue to drift lower. While sellers and the real estate industry may not like it, the reality is that a sleepy housing market may be exactly what policymakers would like to see at this point, and it also holds out the tantalizing potential of some improvement in extremely strained affordability.

That leaves the small matter of wages. The June jobs report must have been a jolt for the BoC. On the one side, the labour market is now very clearly loosening, with the unemployment rate marching steadily upward to 6.4%. Long gone are the days of 50-year lows on the jobless rate and a million job vacancies. Instead, now we are talking about the softest summer job market in more than a decade. Yet, wages simply refuse to relent. Average hourly wages instead accelerated to a 5.4% y/y pace last month. While this particular metric appears to be at the very high end of estimates of wage growth, the back-up will be of some concern to the Bank. And that’s especially so with no productivity growth, and ongoing job actions pushing for big wage gains. Making things very real of course is a strike this very day at Ontario’s Liquor Control Board.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.