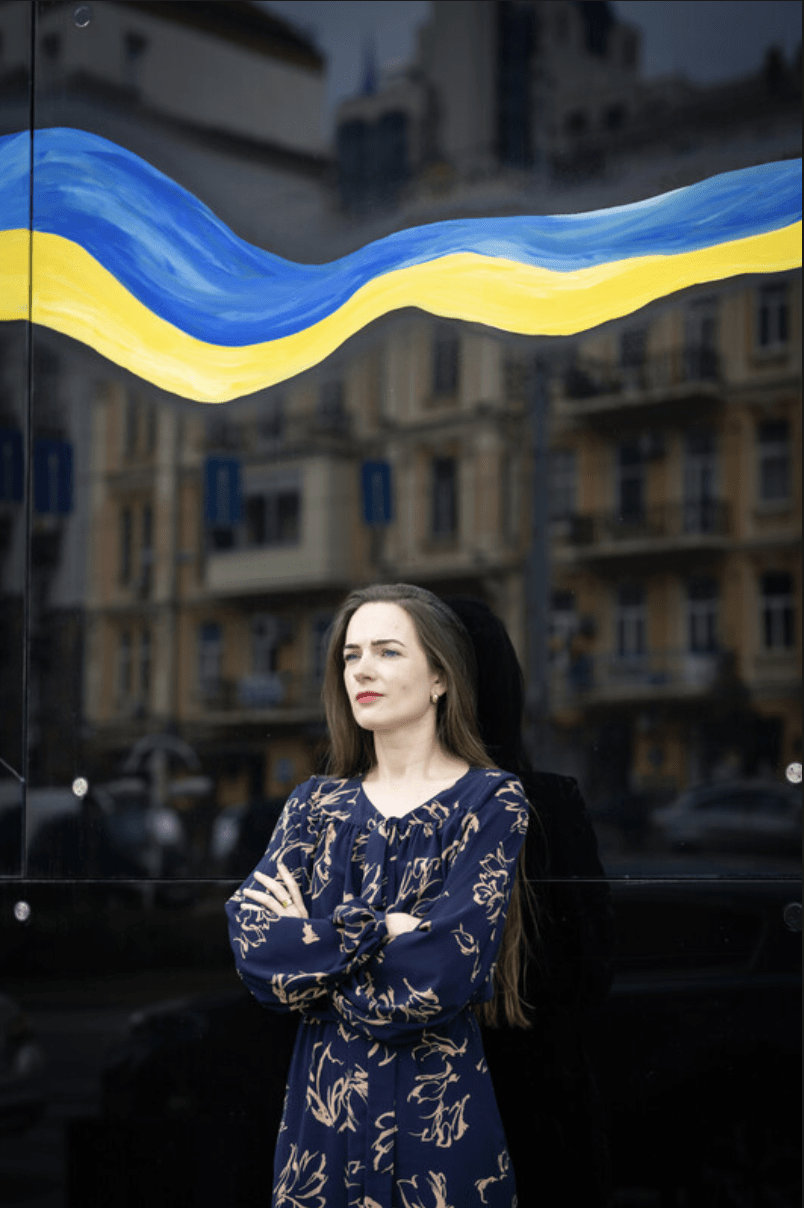

Policy Q&A: Nobel Laureate Oleksandra Matviichuk on Ukraine, Human Rights and Winning the War

Ukrainian human rights lawyer and Nobel Peace laureate Oleksandra Matviichuk will be touring Canada from June 3 to June 9 as a guest of the Canada-Ukraine Foundation. Ms. Matviichuk will visit Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg for more than 30 events, including meetings with senior officials in Ottawa and political and business leaders elsewhere. Here’s our Q&A with Oleksandra Matviichuk, by Canada-based Ukrianian journalist and Policy contributor Anastasiya Ringis.

By Anastasiya Ringis

May 31, 2024

Ukrainian civil society was hardly surprised when the Center for Civil Liberties and its founder, Oleksandra Matviichuk, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022. Instead, this award was perceived as a natural choice.

After all, Oleksandra and her organization defended the rights of Maidan activists during the Revolution of Dignity in 2013-2014 and fought for the release of dozens of prisoners of war from Russian captivity. One of her most famous cases was the release of Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, who spent five years in a Russian prison.

Today, the work of the Center focuses on documenting war crimes committed by Russians against the civilian population of Ukraine. Since the beginning of the war, the organization and its network of partners have reported more than 70,000 such cases.

Oleksandra’s work has been recognized with numerous awards; in person, she is modest and sensitive, ready to explain to everyone how human rights violations in one country can affect the global world order.

Here is our Policy Q&A:

Anastasiya Ringis: What do you think is important for Canadians to know about what is happening in Ukraine in terms of war crimes and human rights abuses being perpetrated by Russian forces?

Oleksandra Matviichuk: I’ve talked to hundreds of people who survived Russian captivity. They’ve told how they were beaten, raped, packed into wooden boxes, electrically shocked through their genitalia, and their fingers were cut, their nails were torn away, their knees were drilled, they were compelled to write with their own blood. One lady told me how her eye was dug out with a spoon. There is no legitimate reason for doing this. There is also no military necessity for it. Russians did these horrific things only because they could.

Unpunished evil grows. Russian military committed terrible crimes in Chechnya, Moldova, Georgia, Syria, Mali, Libya, other countries of the world. They have never been punished for it. They believe they can do whatever they want.

If Russia succeeds and we do not break this circle of impunity, it will encourage authoritarian leaders in various parts of the world to do the same. The international system of peace and security does not work anymore. Democratic governments will be forced to invest money not in education, health care, culture or business development, not in solving global problems such as climate change or social inequality, but in weapons. We will witness an increase in the number of nuclear states, the emergence of robotic armies and new weapons of mass destruction. If Russia succeeds and this scenario comes true, we will find ourselves in a world that will be dangerous for everyone without exception.

AR: The Government of Canada has co-launched and is co-chairing the International Coalition for the Return of Ukrainian Children. What is this issue of the “Stolen Children”?

OM: When we talk about the illegal deportation of Ukrainian children, we refer to at least four categories. The first category includes children who were deported together with their parents, and their fate depends on whether or not their parents found the resources and energy to leave Russia as quickly as possible.

The second category comprises children from state institutions, such as orphanages. We have no means to track their whereabouts or condition. The third category consists of children who were sent by their parents to camps in Russia during battles in their regions. When their cities and villages were liberated, the Russians refused to return these children.

And the fourth category includes children whose parents were arrested and detained in filtration camps or were killed by Russian forces. These children are being prepared for forcible adoption into Russian families despite having parents or relatives in Ukraine.

Ukrainian officials have identified almost 20,000 Ukrainian children who have been illegally deported to Russia, and so far, only 388 have been returned. While the war continues, we don’t have exact numbers on these cases.

Oleksandra Matviichuk/Center for Civil Liberties

AR: That is very chilling. What is being done by your NGO and others to get them back?

OM: The main problem is that currently, there is no legal mechanism that the parents or relatives of the children or Ukraine — as the state of their origin — could apply to stop Russia from committing crimes against the children. Russia has not even complied with the provisional measures ordered by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which in 2022 ordered the withdrawal of Russian forces from the territory of Ukraine. In the international architecture of peace and security, there is little that can be done with a nuclear state that is a permanent member of the UN Security Council with veto power.

For now, the law does not work. Although, I trust that it is temporary. That’s why we are now recording war crimes so that, sooner or later, all Russians who have committed these crimes, as well as Putin and the rest of the senior political leadership and military high command, can be brought to justice.

AR: What are the main challenges your team is facing in investigating war crimes overall? I understand you catalogued over 19,000 in the city of Bucha alone.

OM: We have faced an unprecedented number of war crimes. We united efforts with dozens of regional organizations and built a national network of documentators throughout the country. Working together, we have recorded more than 72,000 episodes of war crimes. It’s just the tip of the iceberg. Russia uses war crimes as a method of warfare. Russia tried to break people’s resistance in occupied territories by inflicting immense pain on the civilian population.

We are documenting more than just violations of the Geneva or Hague Conventions. We are documenting human pain.

We are facing the problem of the responsibility gap. The Ukrainian legal system is overloaded with the amount of war crimes proceedings. The International Criminal Court will limit its investigation to a few selected cases. And the question is who will provide the millions of people the chance for justice?

War turns people into numbers. The scale of war crimes grows so fast that it becomes impossible to tell all the stories. But people are not numbers. We must return people their names. We must ensure justice for all, regardless of who the victims are, their social position, the type and level of cruelty they’ve endured, and if the international organizations or media are interested in their case. Because the life of each person matters.

AR: Ultimately, is this going to The Hague? Because there have also been calls for a so-called” Special Tribunal”. What is the difference between these two models?

OM: The problem is that there is no international court that can prosecute Putin and his acolytes for the crime of aggression. Even the International Criminal Court has no jurisdiction over the crime of aggression in the situation of the Russian war against Ukraine. But all atrocities that we and other people in different parts of the globe document during the war, like war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide it’s the result of someone’s leadership decisions to start the war.

That’s why we must establish a special tribunal now and hold Putin, Lukashenko, and others responsible for the crime of aggression accountable.

AR: What is the message you are bringing to the Government of Canada?

OM: If we want to prevent wars in the future, we have to punish states and their leaders who start such wars in the present. But in the whole history of humankind, we have only one such precedent. And we still look at the world through the lens of the Nuremberg Trials, where Nazi war criminals were tried only after the Nazi regime had collapsed. But we are living in a new century. Justice should not depend on how and when the war ends. We cannot wait.

Politicians often have the temptation to avoid solving complex problems. But if left unresolved, these problems only become more acute. That’s why we need the voices of ordinary people worldwide calling for justice for Russian war crimes. It’s crucial not just for people in Ukraine. We need to prevent Russia’s next attack on other countries.

Russia must be held accountable. This includes not only criminal prosecution for international crimes but also the confiscation and transfer of over 300 billion frozen Russian state assets to Ukraine in Western countries.

AR: Can you tell us about your tour? What will you be doing in Canada overall?

OM: I plan to visit several cities and speak with different audiences. I want to thank people in Canada for their support during this dramatic time in our history. I also want to remind that Ukrainians are fighting not just for themselves, but for the international world order based on the UN Charter and international law, which was established after the Second World War. People in Ukraine are fighting for freedom that has no limitations on national borders. Only spread of freedom makes our world safer.

Anastasiya Ringis is a freelance journalist and communications consultant. Born in Crimea, she has been in self-exile since the Russian occupation in 2014. In 2016, she was formally banned from occupied Crimea, along with other Crimean activists and leaders.