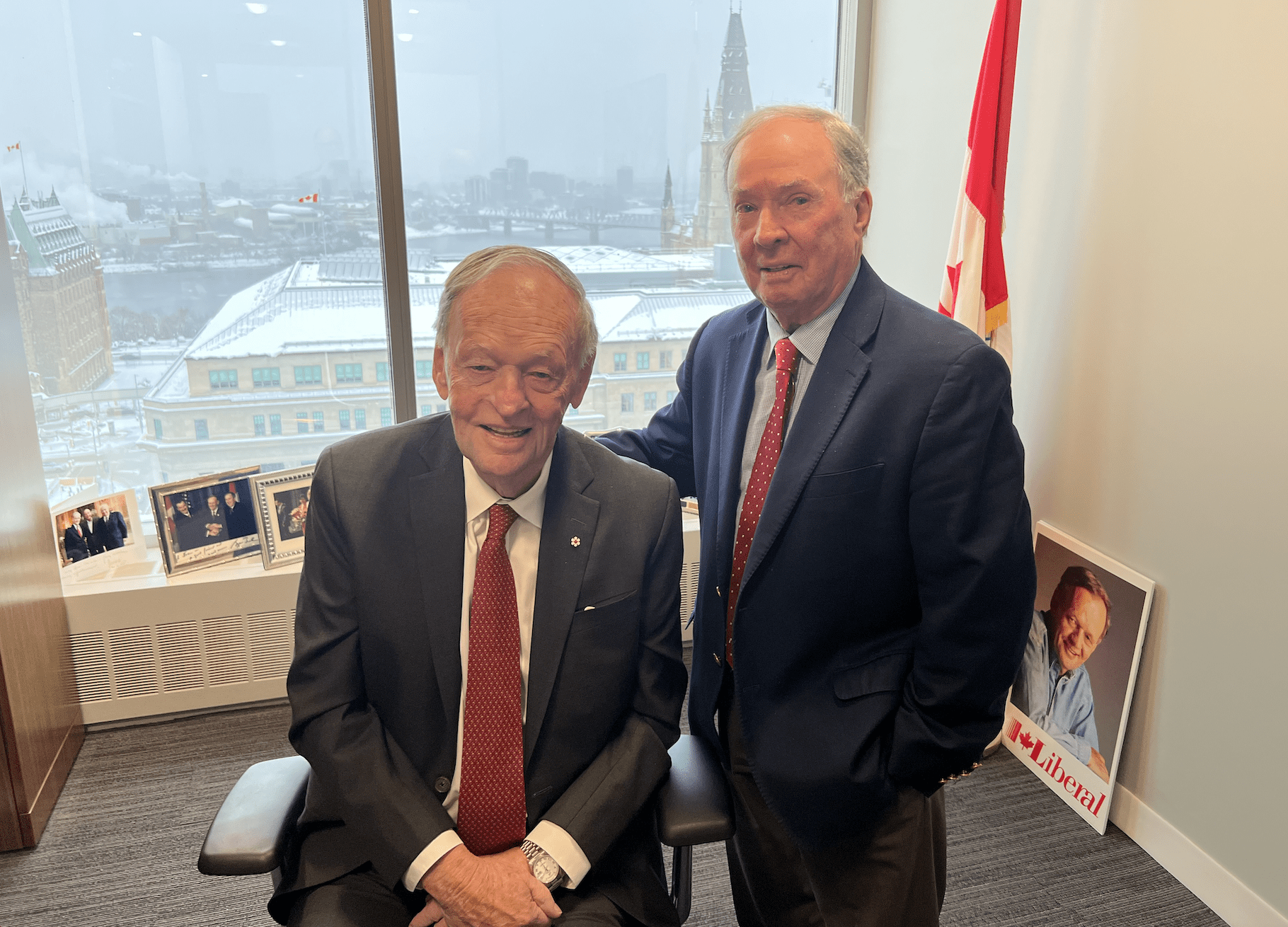

Policy Q&A: Jim Munson with Jean Chrétien, on Loving Canada, Hating No-One and Turning 90

As Canada’s 20th prime minister, Jean Chrétien led the country for a decade, from 1993 to 2003; from the near-miss Quebec referendum of 1995 to Canada’s prescient decision in 2003 to stay out of the Iraq war. With Chrétien’s 90th birthday approaching on January 11th, former PMO communications director, retired senator and Policy contributor Jim Munson sat down for a chat with his former boss in his Ottawa office at Dentons.

December 8, 2023

Jim Munson: As you turn 90, what gives you a sense of purpose these days?

Jean Chrétien: You know, my father always liked to say, in French, “Grouille ou rouille!”, or, “If you don’t move, you rust.” If you retire and buy a rocking chair, you don’t last very long. So, I’ve been very active, and it’s been very interesting. When you’re 90 and you feel you’re still useful, it’s great. And the more you’re involved, I think the body follows the work of the brain. I leave my home every morning at 9:00 o’clock for the office four mornings a week.

JM: What motivates you the most?

JC: I’ve been involved in public life since 1956 — I was making political speeches in the provincial election campaign at 22 and we voted at 21. I’ve always enjoyed political life, even in the last 20 years — it’s a great activity and I always had good motivation.

JM: You went from being a tough young politician — “Le p’tit gars de Shawinigan”, to an elder statesman — Canadians are familiar with your public story. What do you do to relax — is it the visual arts, music?

JC: I’ve always been interested by the arts, music, reading. There are 24 hours in a day, so I’m rarely sitting doing nothing. I read, I listen to music, watch TV and play golf in the summer. I don’t ski anymore because my family says I shouldn’t but I could. But I’ve always been very private about my private life. My son was telling me the other day he has appreciated that I never used him in politics. Of course, Aline was involved because she was my wife and a very respected first lady in Canada but she did not make speeches and try to be in the news. She ran away from that. She’d say, “There’s only one person on the stage, and that’s you.”

JM: How did your sense of Canada — your love of the country — develop?

JC: From knowing it. When I started, I was a little bit — there were a lot of nationalists in Quebec putting pressure on you — and one day, I had a discussion where a guy woke me up to reality. He said, “Jean, you’ve never been outside Quebec. Before dumping on Canada, why don’t you know about Canada. And that shook me up, and I said to myself, “You’re right. I’m wrong.” I’d been in Ottawa a couple of times and that’s it. I’d gone once to new Brunswick and PEI.

JM: New Brunswick’s a good start!

JC: Hey, I went on the North Shore, that’s for sure. Of course, I was elected at 29 and I started to travel right away and I was a minister in 1967 — it was Centennial year — so I had to go and represent the federal government on all sorts of occasions, in the Prairies, I travelled across Canada on a Train, stopping in Northern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and B.C. I went by CP and came back by CN. There was a private car at that time for the government. So, I learned quite a lot and developed a great love for Canada.

JM: Was there a particular moment when you felt in your soul that you had a vision for Canada?

JC: I learned a lot more than I knew when I was in rural Quebec. I developed a knowledge of Canada and I developed a knowledge of the quality of the nation and I developed a knowledge of the diversity of the nation — even more when Trudeau named me minister of Indian and Northern Affairs. I visited Indian reserves and I visited the Yukon and Northwest Territories and I started to understand the fabric of the nation and I came to understand that there is not great discrimination in Canada. We don’t have ghettoes based on colour, race or religion. When you go to Montreal and you see the evolution across the city, it’s based on money — from the east end to Outremont and Westmount — not other factors.

The problem today is that it is democracy that’s being challenged — that’s what worries me. When you see what’s going on in the United States with the Trump gang — the ‘MAGA’ who would retaliate against anybody and throw them in jail. This is America! That is worrying.

JM: The most consequential decision you made as prime minister was not to join the United States in the war in Iraq. We know why you made that decision and I was in the room when that decision was made. How did you get yourself mentally and emotionally to the point where you could make that decision?

JC: I knew they were thinking about it. Probably the critical moment was in August, the year before the war, I was in Detroit. I had a meeting with George W. Bush and he had asked for an hour and a half and after 20 minutes, it was over. I said I will not go there if you don’t have the support of the UN and to have the support of the UN you need better proof of weapons of mass destruction and you don’t have the proof. I wrote at the time that there wasn’t enough proof to convince the judge at municipal court in Shawinigan. When you want to go to a conclusion you will find in the briefing what you want. For me, I was outside of it. I was very objective and so he put a lot of pressure. Tony Blair even more. But for me, I thought they were wrong. And I said no. There were consequences for me — the right-wing armaments industry never invited me to make speeches for money after I quit politics.

JM: What worries you about the world today? When you look at the headlines, at the complexity of events, how can anyone lead in times like these?

JC: I was the president of the Young Liberals at Laval university in 1956 and it was never an easy time. When I was elected in 1963, there were bombs in the streets of Montreal. Years later, there were bombs in London every day. Now, we think it’s terrible. Yes, we have a war in Israel — it’s not the first time. We have a war between Ukraine and Russia but there was a war in Vietnam and Afghanistan. The problem today is that it is democracy that’s being challenged — that’s what worries me. When you see what’s going on in the United States with the Trump gang — the ‘MAGA’ who would retaliate against anybody and throw them in jail. This is America! That is worrying. Democracy is being challenged not just in the United States but in Europe, with the hard right is getting more popular. Russia was moving toward democracy and they’re not anymore. It is the same thing in Poland, and Hungary, and the Netherlands and Argentina and Italy. I hope that, and I think that, democracy will prevail. As Churchill said, it’s not a very good system but there’s nothing better.

JM: In your book, My Stories, My Times, on the very last page, you quote Sir Wilfrid Laurier saying, “Faith is better than doubt, love is better than hate.”

JC: It is true. You need social values and to have faith is a very stabilizing element in any personality, in the life of any person. I am a believer and it is extremely private but I find that it is an extremely stabilizing force in my life. And, we have to live with people, so love is much better than hate. Hating somebody, you gain nothing. For me, I was the object of some hate at some times because some separatists hated my guts in Quebec. But I didn’t pay much attention. I remember one day I was in a restaurant and a guy had had a few drinks and he said, “What the hell, Chrétien, you’re here! I never voted for you,” and I said, “You have the right to be wrong, sir.” And then he said, “I’m a separatist. But I want to tell you, you were a very good prime minister for Canada.”

JM: That sums it up.