Policy Q&A: Former G7 Sherpa Sen. Peter Boehm on Trump, Charlevoix and Bracing for Kananaskis

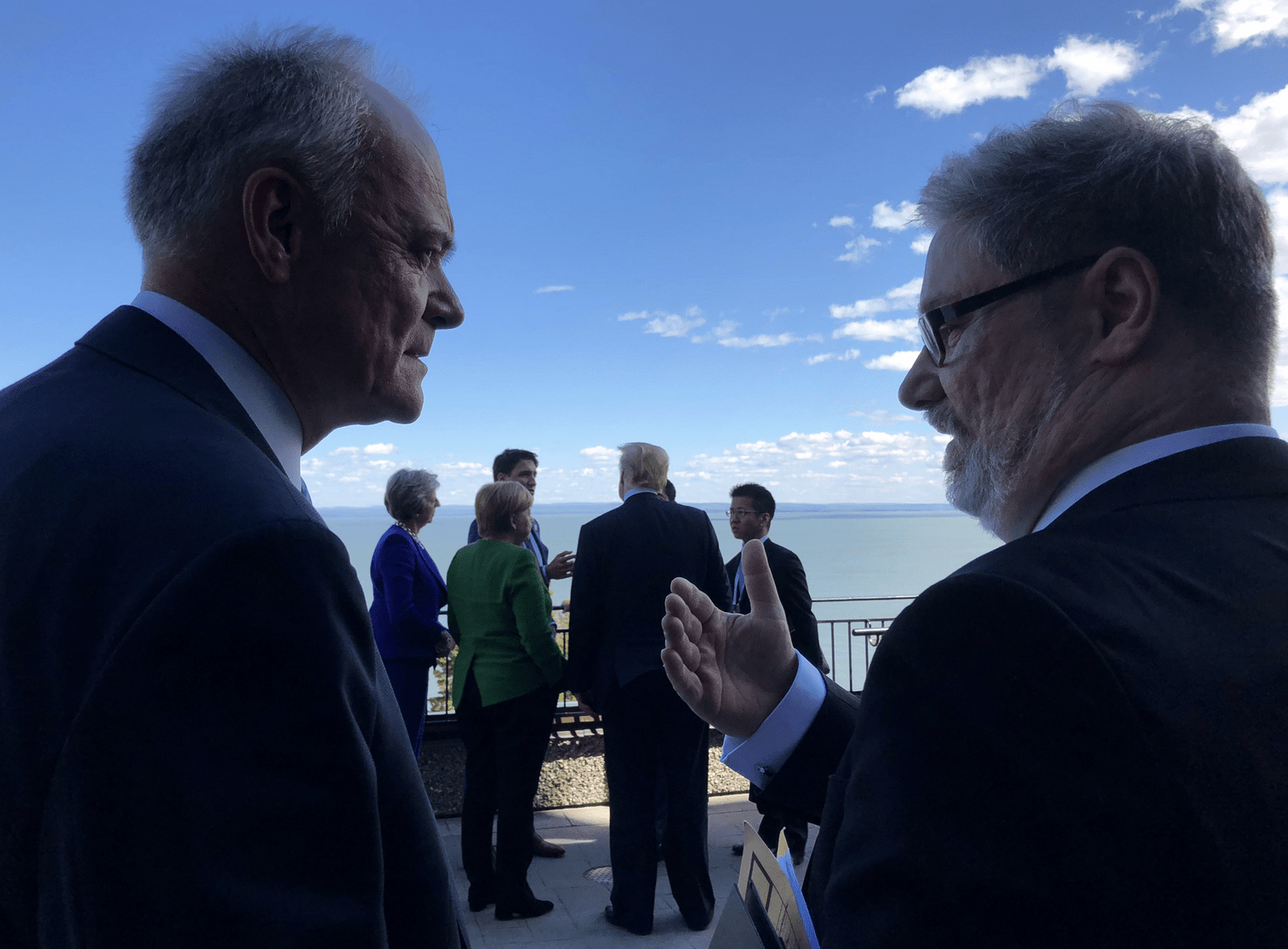

Sen. Peter Boehm, far left, in the famous ‘intervention’ shot from the Charlevoix G7, 2018/Adam Scotti

Sen. Peter Boehm, far left, in the famous ‘intervention’ shot from the Charlevoix G7, 2018/Adam Scotti

Senator Peter Boehm has served as Canada’s Sherpa for six G7 summits, including the last Canadian G7, at Charlevoix in 2018, which provided him with an exceptional tutorial in the diplomatic stylings of Donald J. Trump. With trolling Canada already a theme of Trump’s second presidency, Policy Editor Lisa Van Dusen reached out to Senator Boehm in late January for his insight and guidance as Canadian officials brace for the Kananaskis G7 in June.

Lisa Van Dusen: Senator Boehm, I know you’re unfailingly diplomatic, but all this must be a little surreal for you. After your experience with Donald Trump in Charlevoix in 2018, he is not only president again, but he’s threatening to impose coercive tariffs on Canada, and may well reprise his spoiler role at Kananaskis in June. What do you make of it?

Sen. Peter Boehm: After six years as a parliamentarian, I may have lost some of my diplomatic DNA and therefore feel rather emboldened in expressing myself on this subject.

There have always been surreal moments over the 50-year existence of the G7 (including the 17 years with Russia as the G8) I witnessed a few over the years, even before taking on Sherpa duties. Having Russia in the group as the G8 for 17 years had its own peculiar dynamic. Election outcomes and leaders’ resignations occasionally meant that someone brand new was at the table, often flailing to be a meaningful part of the conversation in an unaccustomed forum. There were forced, sometimes awkward cross-cultural moments. Over time, the G7 adopted a predictable routine: the host country took on the presidency at the beginning of the calendar year, it set out a planned agenda of ministerial and Sherpa meetings, relying to some degree on leftover business or continuity from previous summits and initiatives that reflected both reaction to international events and themes the host country wished to press. Much was distilled into the final communiqué, satisfying the bureaucrats and largely ignored by the media.

The summits following the departure of Russia — in Germany (2015) and Japan (2016), where I surprised my colleagues and some leaders by having been retained by Justin Trudeau after three summits with Stephen Harper — went smoothly and in some ways were a throwback to earlier times in terms of orderly process and approach by the member countries: inputs from ministerial meetings, initiatives and a final communiqué indicating consensus among the leaders on a variety of subjects and plans for follow-up. (To get a sense of how this approach can be effectively satirized in a surreal fashion, do watch the comedy-horror film Rumours and read my review in Policy).

Everything changed again in 2017 when President Donald Trump attended his first G7 summit in Taormina, Sicily. We Sherpas had a sense that the US was coming at the themes from a different angle: skepticism over remaining part of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, disagreement with the “JCPOA” deal regarding Iran’s nuclear programme, social policy issues (particularly on women’s reproductive health) as well as other matters. The Americans were not thrilled with any agreed language that would commit the US to a common approach and we all saw a palpable, if unfocused desire for America to be the G-1, and with it a greater readiness to pursue its own path. This had an impact on the final communiqué, a document of more traditional importance for the Europeans and the Japanese than for us. Nonetheless, President Trump was an avid listener, was polite and made few interventions.

Justin Trudeau and Peter Boehm discussing strategy ahead of the 2018 Charlevoix G7/John Zerucelli

Justin Trudeau and Peter Boehm discussing strategy ahead of the 2018 Charlevoix G7/John Zerucelli

One discussion that stands out in my memory was his request to have leaders take turns in explaining the virtues of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. German Chancellor Angela Merkel mustered an impressive argument, followed by equally persuasive interventions by French President Emmanuel Macron and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. When they were finished, President Trump took the floor, commented on their outstanding performances and said, “I think Justin won this one”. I subsequently congratulated the Prime Minister on not being “fired” and for becoming the new “apprentice” (we laughed but not so much now). A week later, the US withdrew from the Paris Agreement (as it has done again). So much for the policy impact of the leaders on the US President. Both the Prime Minister and I were taking many mental notes as to how Trump approached the discussions, all with a view towards the strategy we would develop for Charlevoix the following year.

It is always tough following Italy in the G7 presidency. The Italians run their ministerial and Sherpa meetings well and their summits are superbly organized and executed. Last year, they held some twenty-two ministerial meetings in various locations. No expense is spared and bella figura is important. This is very much in contrast to Canada, where the first question posed by either the (Canadian) media or the political opposition to the leader at the conclusion of a summit is how much the entire enterprise has cost taxpayers. Never mind the purpose or the results. So, the six previous presidencies of Canada have always featured a back-to-basics, more streamlined approach. I suspect this year at Kananaskis will be no different in that respect.

The last time, for Charlevoix, we started early. Mr Trudeau led a majority government, already had experienced two summits and knew what focus he wanted to bring. He dispatched me to G7 capitals to meet with my counterparts to sell the emerging agenda. He called all the other leaders. I went to Washington numerous times to meet with various interlocutors in the White House on both the economic and national security side as well as the Sherpa (the previous one having been removed following the Italian summit). There was much churn among officials in the White House and it was not at all clear to me whose advice mattered, who was taking decisions, who had the ear of President Trump, under the assumption that he was listening, and indeed how the US inter-agency consultative system was addressing the G7 agenda. This in itself was not that unusual (I recall the Obama administration being slow to react). For the Americans, the G7 is just another element of a grand foreign policy; for us it is arguably the jewel in the crown.

In a quick conversation I had with President Trump it was clear to me that he had not been briefed in any detail. He said he was concentrating on his meeting with North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un in Singapore a few days hence.

In outlining plans for the summit, including logistics and local impact, I met with the Premier of Québec, Philippe Couillard, the mayor of Québec City, Régis Labeaume (who joked that we must be relatives), local leaders and the regional indigenous peoples’ leaders. During the lead-up to the summit, in Ottawa I would meet with the Prime Minister and his PMO team at regular intervals, I chaired a deputy minister’s committee of all involved departments and agencies (ie most of government), briefed Cabinet and met on occasion with Governor General Julie Payette to keep her informed of developments. I was fortunate to be given free rein with the media. I mention these integral aspects to offer a sense of what will be required to pull off the summit in Kananaskis.

For Charlevoix, I knew that summit planning was going to become more difficult as we neared the summit date in June 2018. The event planning moved smoothly as we had a few summit veterans with us. The summit agenda, not so much. It was clear that the US had problems with the consensual language agreed to with the Europeans and Japan on climate change, Iran, references to the “rules-based international order” and a few other subjects. Also, as Sherpas we had worked together to develop a mutual notification mechanism on Chinese dumping of steel and aluminum (among other China-related matters) into our markets that would go beyond current OECD efforts. The Americans had agreed to this. Just before our Sherpa meeting in Victoria in March. I received a call from my US counterpart, Everett Eissenstat, to inform me that at President Trump’s request the US would not agree to the mechanism and instead would impose tariffs on steel and aluminum exports from Canada. He added that we shouldn’t feel too bad because Japan and the Europeans would be getting the same treatment.

With the summit approaching, we had to come to some decisions as to whether negotiating and achieving an ambitious consensual communiqué was still possible or whether we would simply be left with a series of lowest common denominators. We managed to get tacit agreement on our six initiative documents and most of the draft communiqué subject to leaders’ review at the last Sherpa meeting at Baie-St-Paul two weeks before the summit. Nonetheless, I had a draft Chair’s Statement prepared (not without precedent) should things really go sideways. This was our first indication that Trump could indeed be serious about imposing tariffs, which he did the following March, accompanied by a tweet that asserted, “Trade wars are good, and easy to win.”

Trump did not torpedo our summit, but it was close. As leaders and their delegations gathered at the site in La Malbaie, there were a number of informal discussions among leaders and key advisers on the first evening (see couch photos). Sherpas then convened for an “all-nighter” negotiating session. U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton and economic advisor Larry Kudlow had joined the US delegation for the negotiations, both without any real knowledge of the agenda (or the G7 for that matter) and both senior to their Sherpa. They did, however, have some influence over their leader. The discussions became more complex to the particular annoyance of the Europeans. In a quick conversation I had with President Trump it was clear to me that he had not been briefed in any detail. He said he was concentrating on his meeting with North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un in Singapore a few days hence. Indeed, his subsequent lacklustre performance in the discussions underscored his lack of preparedness.

We managed to resolve our differences during the all-night sessions: a separate paragraph in the communiqué from the US indicating that it would not join consensus on the climate change wording; circumlocutory language on Iran that referenced UN Security Council resolutions. Where we still had difficulty was in references to the “rules-based international order” which was eventually resolved between leaders and a rather bemused looking President Trump. The photograph of that moment (where in most versions my head and the Prime Minister have been cropped out), which looks like an intervention, has become iconic.

Chaos diplomacy? The Charlevoix G7, 2018/Adam Scotti

Chaos diplomacy? The Charlevoix G7, 2018/Adam Scotti

We tried to make it easy for President Trump with some planned meeting choreography. In my view, Prime Minister Trudeau was a skilled chair, beginning the leaders’ private meeting (plus Sherpas) with a nod to President Trump to begin the discussion of the global economy, perhaps with references to his tax cut and its impact. Trump warmed to the subject, engaged but then wilted and lost interest when Chancellor Merkel and President Macron provided their assessments on economic growth and challenges.

Later on, he lamented the fact that Russian President Vladimir Putin had not been invited, much to the discomfort of UK Prime Minister Teresa May who was dealing with the fall-out from the Russian novichok poisonings in Salisbury a few months earlier. My recollection of the bilateral meeting with the Prime Minister was that it focussed almost completely on next steps for NAFTA and forthcoming negotiations, with active disagreement between the two on a proposed “sunset clause”. Trump wanted to leave the summit early, avoided the discussion on climate change and wished to give his press conference first (an unkind and clumsy demand since this is always the prerogative of the host).

He was indifferent regarding the “outreach session” that featured the participation of a dozen additional leaders and the heads of international organizations for a discussion on the impact of ocean plastics. Unhappy, he retreated to Air Force One for his departure and watched Prime Minister Trudeau’s concluding press conference. Most media questions were about the discussions with President Trump and the Prime Minister gave an accurate rendering of the discussion in the bilateral meeting. In a moment of pique, President Trump fired off a very negative tweet (it was still Twitter then) and asked his officials to try to suppress the issuance of the summit documents and remove his signature. It was too late and there never were any signatures. Leaders had signed a posterity scroll for the town of La Malbaie. Joined in vituperation by his loyal acolytes, his war of words continued.

We had survived and the Charlevoix communiqué, initiative statements and documents and agenda went forward. France chaired the process and hosted the summit the following year, with Trump missing his turn in 2020 because of the Covid pandemic.

As Canada prepares for Kananaskis, our seventh summit and the 51st in the series, there are a number of “known unknowns”. First, it is unclear who will be the prime ministerial host and in that context what Canada’s thematic priorities will be. A change in government will almost certainly cause some priorities to change. Second, there will only be time for some hastily arranged ministerial meetings supporting the process and the agenda before June. Foreign and finance ministers’ meetings will be key. Ditto on Sherpa meetings to plan the discussions.

In my view, given the politics, the timing crunch, the rise of the BRICS, and the ‘known unknowns’, Canada should plan for a ‘G7 Lite’ summit and agenda as a bid to strengthen if not save the institution.

But there is more. With Trump’s aversion to multilateral meetings, it is not clear whether he would even wish to attend or whether he would make the promise of his attendance contingent on some unknown concession on Canada’s part. Or a concession on the part of the collective. Invite Vladimir? Unlike in our system, it is highly unlikely that he will receive dispassionate, reasonable policy guidance from advisors he has favoured for their loyalty over any knowledge or judgment they may possess. Or would he simply wish to be present to draw attention and be a spoiler?

He is already upsetting us and the Europeans with his threats and statements. Will things get to a point where there might be a meeting of the G-6 with the number-one agenda item being a discussion on how to deal with the US? Will this venerable, informal global institution fall apart? Given Trump’s repeated statements and odd musings about Canada during the first days of his presidency, one could argue that anything is possible.

In a very short period of time, a new prime minister will need to rely heavily on the Sherpa and the senior public service for advice, guidance and counsel. Close coordination with the “like minded” (and working hard with the US) will be essential. This will require an investment in personal diplomacy at the very top that will be time consuming. To say nothing of luck. In my view, given the politics, the timing crunch, the rise of the BRICS, the “known unknowns” I have mentioned, Canada should plan for a “G7 Lite” summit and agenda as a bid to strengthen if not save the institution.

Lisa Van Dusen: You’ve served as chair of the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade since 2020, so you must have strong views on Trump’s tariff threats.

Sen. Peter Boehm: I will always recall the conversation I was having in the boardroom at our embassy in Washington on the morning of 9/11 with Ambassador Michael Kergin and our executive team. The subject was the softwood lumber dispute, where again Canadian exports had exceeded one third of market share in the US and the American producers’ alarms had gone off. Obviously, the events of 9/11 quickly took over our work that day and beyond, particularly on what became the “Smart Border Action Plan”, yet the “hardy perennials” of our trade relationship with the US continue to complicate. In “pull-asides”, I have stood with Prime Ministers Paul Martin, Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau when Presidents George W Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump raised the plight of the Wisconsin dairy farmers and US concerns with our supply-managed agricultural sector (dairy, eggs and poultry). We were always tough and principled on these irritants.

For Donald Trump, tariffs are a binary measure or weapon that theoretically can be turned on and off at will. Any tariff measures levelled against Canada and/or Mexico, regardless of the percentage, will have a deep impact on established and integrated supply chains, trading patterns (think Canadian Pacific Kansas City Ltd with its 32,000 kilometres of railway connecting the three North American countries) and of course consumers. All the while, GDP growth rate projections of the CUSMA partners exceed those of most OECD countries. If Trump is indeed proposing a 25% tariff, it will make the impact of the 1930 Smoot Hawley tariff – that caused a global trading downturn of about 60% — look like a parlour game.

On the other hand, with CUSMA already set for review next year, his rhetoric may be a move to bring both Canada and Mexico to a renegotiation earlier so that, so that in a reprise of the last time when he insisted that NAFTA needed to be renegotiated, he hailed the result as “a truly extraordinary agreement”, heaping praise on both Justin Trudeau and then Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto. In the interval, before his inauguration, he irked Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum and Trudeau with tariff threats rationalized by border concerns while also suggesting that CUSMA was unfair and the US was being “ripped off”. The fact is, a trade imbalance is not a subsidy, and portraying it as one to justify either leverage or belligerence is disingenuous at best.

Peter Boehm in a pull-aside with German Sherpa Lars-Hendrik Röller as G7 leaders meet at Charlevoix/Adam Scotti

Peter Boehm in a pull-aside with German Sherpa Lars-Hendrik Röller as G7 leaders meet at Charlevoix/Adam Scotti

Lisa Van Dusen: From your perspective after years of being immersed in foreign policy and Canada’s place in the world, what do you think is the most serious threat to our future at the moment?

Sen. Peter Boehm: Without a doubt in my mind, both the threat and the challenge to our global future is the United States turning its back on the multilateral system it was instrumental in creating after the Second World War. This applies to both the United Nations and its specialized agencies and the Bretton Woods financial institutions. Pulling out of the World Health Organization, as opposed to making an effort to reform it with the prospect of yet more global pandemics, cedes the terrain to both state and non-state malign actors. Flouting the charters of the United Nations, regional organizations (hello Panama and the OAS), actively coveting the territory of another NATO member, all go against the values the US has propagated for the past eight decades, generally with success and with the help of staunch allies it now appears to want to undermine. Might is not right; might means exercising enlightened influence, diplomacy, letting others have your way. International relations are not governed by pulling out pages from The Art of the Deal. As the world’s third-oldest constitutional democracy, Canada has been a player, a voice of reason and compromise. We should continue to exercise our influence consistently and where we can, while being a good neighbour and an astute, ecumenical global actor. Perhaps that is our own manifest destiny.

Lisa Van Dusen: Thank you, Senator.

Senator Peter M. Boehm, a regular contributor to Policy magazine, is a former ambassador and deputy minister and, at prorogation, was chair of the Standing Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade.

Policy Magazine Editor Lisa Van Dusen has served as a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.