Policy Dispatches: Meeting History — Past and Present — Along the Danube

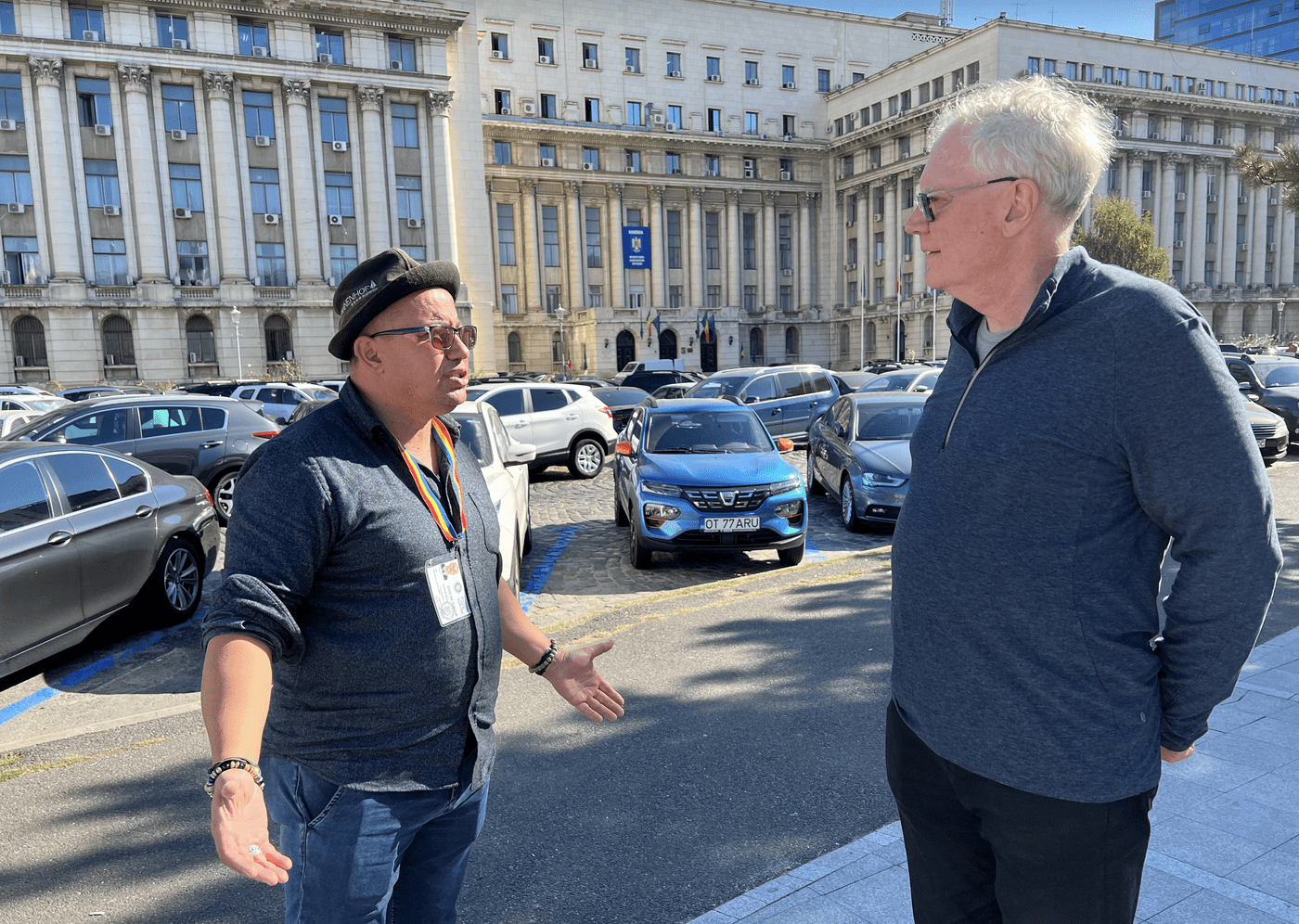

With tour guide Mihai outside the former Communist Party HQ in Bucharest’s Piata Revolutiei/photo Maureen Boyd

With tour guide Mihai outside the former Communist Party HQ in Bucharest’s Piata Revolutiei/photo Maureen Boyd

By Colin Robertson

November 8, 2022

Delayed by the travel constraints imposed by the pandemic, my wife, Maureen, and I finally embarked on our voyage along the Danube — three years later than planned and at a time when Europe is once again embroiled in a ground war.

The Danube is not Europe’s longest river; that’s the Volga. Nor does it carry the commercial traffic of the Rhine. But when it comes to the popular imagination, the Danube is to Europe what the Nile is to Egypt and the Mississippi is to America; a physical feature of the landscape whose place in the culture is amplified by a thousand songs and stories. For my mother, New Year’s Eve was not complete without the concert from Vienna that always featured Johann Strauss’s Blue Danube waltz.

Three thousand kilometres long, it flows through 10 countries, including four European capitals — more capitals than any other river in the world. Its basin covers 20 percent of European Union territory, containing around 115 million people. We travelled 900 miles aboard the Avalon Waterways 164-passenger Passion. We boarded in Bucharest, cruising east toward the Romanian port of Constanta on the Black Sea, before returning upriver through Romania with stops in Bulgaria, Serbia, Croatia and Hungary.

We left the ship in Budapest, where it later continued its voyage into Austria and then to the source of the Danube at the confluence of the Brigach and Breg headstreams near Donaueschingen, Germany.

While the right combination of location, company and craft, traveling by ship is remarkably agreeable. No fuss about packing and repacking or changing hotels. Docking within walking distance of the historic heart of these port cities is another major attraction — no parking worries, someone else does all the navigating and the guides were capable and well-informed.

One guide told us that his grandmother lived in four different countries in her lifetime — all at the same address. Others were not so lucky, and flight from war and oppression have produced cycles of major displacement.

While there is no universal agreement on which countries are included in the toponymic label “the Balkans” — broadly defined in geographical terms by Eastern Europe’s Balkan Peninsula — the list usually includes Romania, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Slovenia, Serbia, Kosovo and Croatia. Historically, it is where Occident met Orient for trade and commerce. It’s where empires clashed — Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, Romanov, Hapsburg — earning it the title “Powder Keg of Europe”. In the last century, it suffered first Nazi then Soviet invasion and occupation, followed by more than a decade of war and ethnic cleansing across the former Yugoslavia through the 1990s.

Throughout the region’s history, boundaries were constantly redrawn without much regard for concentrations of race, religion or ethnicity. One guide told us that his grandmother lived in four different countries in her lifetime — all at the same address. Others were not so lucky, and flight from war and oppression have produced cycles of major displacement. The result is a hodgepodge of languages, alphabets and nomenclature — concentrated into a geographical space the size of Alberta but with a population of around 60 million.

By Canadian standards, the geography of the Balkan states may be small but their nationalism, history, myths, animosities — all wound into their traditions and distinctions, including religion — still matter profoundly. Often, those divisions have been delineated in blood.

They still register in daily life, including by omission. We remembered skiing at Whistler, where name tags of lift attendants and other staff indicate their country of origin, yet our cruise staff wore only name tags. We asked our Serbian captain — a 34-year-old Roger Federer look-alike — why the multinational Balkan crew did not include their home countries. “I’m trying to create a team. We have too much divergent history…like the EU, we now need to work together.”

Crossing borders was easy, with the exception of Viktor Orban’s increasingly “illiberal” Hungary. The zealous passport officials obliged the 42-member crew and all 82 passengers to show their faces at 6:30 a.m. We had no idea there was such variation in sleepwear.

Our voyage up the Danube gave us a riverside view of the CANDU reactors in Cernavoda, Romania that were originally installed beginning in 1982. Two of the five are still operating and generate 20 percent of Romania’s electricity. It’s a technology that Canadians once led and should again, given Europeans urgent requirement for carbon-free energy.

While touring Bucharest — still aspiring but not yet quite fulfilling its ambition to be the “Paris of the Balkans” — I asked our guide what he thought of communism. Mihai, sporting a name tag ringed with a Romanian flag-inspired red, yellow and blue ribbon and a pork barrel hat that made him look like Elmer Fudd, replied “bad times”. In a nod to George Orwell’s Animal Farm, he continued, “We were all equal but some were more equal than others.” What decided the end of the Cold War? Mihai said it was simple: “Blue jeans, the mini skirt and rock and roll.” A week later, in response to the same question, I got a similar reply from Vicki, our Hungarian guide: “Blue jeans, books and Coca-Cola.” Communism could not compete.

Buying his first vinyl — a second-hand Pink Floyd — on the black market in 1989 was a memorable moment for the 18 year-old Mihai, then serving as a paratrooper during Romania’s December Revolution. Viorica, our guide in Belgrade, preferred Jim Morrison and the Doors. She agreed that what convinced her generation that communism did not work was American culture and the portrayal in American popular films of the cornucopia of choice offered in American supermarkets and department stores.

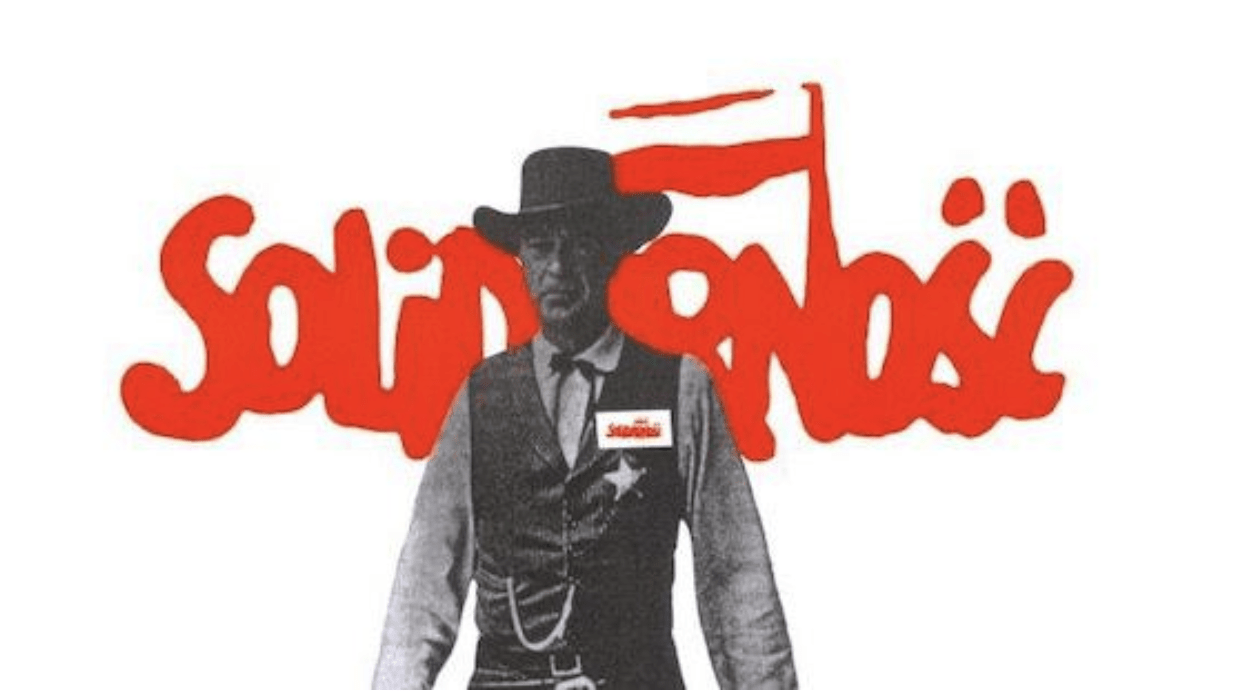

It took me back to my time as Consul General in Los Angeles and an exhibition called Western Films Through Polish Eyes at the Gene Autry Museum of the American West. Who would have guessed that the poster of the 1952 High Noon — my favourite western — would be appropriated by the pro-democracy Polish workers movement and political force Solidarity in 1989 (above) as the nation faced its first election in 40 years? As the visiting Solidarity leader and first elected president of post-Soviet Poland Lech Walesa later told me, what’s not to like about Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper), facing down the vengeful Miller gang when everyone else in town had opted for appeasement?

The end of communism across the Balkans was mostly peaceful but Romania’s revolution was not a velvet one. More than a thousand people were killed before — after a perfunctory trial — dictator Nicolae Ceauçsescu and his wife, Elena, were publicly executed on Christmas Day in 1989. Before that indelible end to Romania’s dictatorship, our guide Mihai’s brother was nearly killed by friendly fire when dispatched to the nine-story underground shelter for the nomenklatura. In a fog-of-war episode, Securitate secret police were firing on Romanian troops. Each side thought the other were terrorists. There were no terrorists, just frightened young men led by equally frightened old men. Mihai’s brother is now an architect but keeps his helmet with the bullet crease as a reminder of how close he came to death.

Urban Wanders

Urban Wanders

The police-state side of life in the Soviet satellites is graphically portrayed in Budapest’s House of Terror Museum (above). During Nazi times, it was the home of the secret police. When the Soviets conquered the city in 1945, many just changed their uniforms, learning new terror tactics from new masters.

With Marxist-Leninism swept into history’s dustbin, religion — Orthodox, Catholic, Muslim — re-emerged in the Balkans. Our guide in Belgrade shared the tale of the city’s late archbishop, who asked who owned all the Range Rovers, Mercedes and Lexuses waiting outside a conference of bishops. “Why, the bishops!” replied his acolyte. The archbishop, a humble man who repaired his own shoes, quipped, “Just think what they’d be driving if they had not taken a vow of poverty.”

Under communism, Tito had stilled Yugoslavia’s Orthodox, Muslim and Catholic tensions through authoritarian control but, as with tyrants elsewhere, history filled the vacuum of his passing. Of course, religion played its part in the horror that consumed the former Yugoslavia during the 1990s under the brutal rule of Serbian leader Slobodan Milošević. The genocide Milošević committed against first Bosnian, then Kosovar Muslims was a catalyst for the creation of the International Criminal Court in July 2002 and the adoption, in September 2005, of the United Nations Responsibility to Protect (R2P) principle. Canada played an instrumental role in both initiatives.

In the wake of the bloodbaths of the 1990s rationalized by religion and ethnicity, the nations of the former Yugoslavia have sorted themselves into religious and ethnic enclaves: Croatia and Slovenia majority Catholic, Serbia majority Orthodox, Kosovo majority Muslim, with splits in North Macedonia as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In a part of the world famous for long memories, the most recent war remains fresh in the minds of people. In Ilok, we visited a winery dating back to the Romans where, in October 1991, Croatian vintners used bricks from medieval times (adding mold as camouflage) to hide their archival wines, including some served at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, from marauding Serb forces.

Our Croat guide, who worked for the BBC’s Martin Bell during the war, told us that she still never takes a bath as it took so long to jump out and run to the shelters whenever Serbian bombs began falling. We visited Vukovar, once home to a Bata shoe factory employing 22,000 before the war. Now it employs 800. Like the rest of the Balkans, the Croat population is declining as a result of aging and migration, with many of their youth going to Ireland, in part because the landscape and sociability remind them of home. The Irish welcome their talents and, as in the rest of the Balkans, English is now the second language of young Croatians.

English is also the language of our Danube vessel. Unlike with air travel, where ICAO has made English the working language, the Danube Commission in 1954 set theirs as German, Russian and French. Our Serbian captain told us that an EU study found the cause of most accidents on the Rhine and Danube was confusion over language. So, he and the crew use English, a practice he says all river traffic should adopt.

Our guides, unprompted, repeatedly said, ‘Thanks be to God for NATO’. Exercises on the Danube based on the enhanced NATO presence obliged our ship to get to Budapest a day earlier than scheduled. The one question on which everyone we met agreed: nobody wants a return of Russian hegemony in Eastern Europe.

Europe’s latest deadly conflict — the ongoing war started by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s illegal invasion of democratic Ukraine in February — has affected trade and commerce. In Constanta, Romania’s port on the Black Sea, the waterway is busy with barges carrying diverted Ukrainian grain and fertilizer that is loaded into ships sailing through the Dardanelles into the Mediterranean.

The Balkans have always had to balance between the great powers and they still do. But collectively and individually, the people we met are glad to be in the West. Our guides, unprompted, repeatedly said, “Thanks be to God for NATO”. Exercises on the Danube based on the enhanced NATO presence obliged our ship to get to Budapest a day earlier than scheduled. The one question on which everyone we met agreed: nobody wants a return of Russian hegemony in Eastern Europe.

Walking along a street in Budapest, we happened on the open-air exhibition Hope and Tragedy: Hungary ’56 a display of recently discovered photographs from the brave 1956 Uprising against the country’s Soviet-imposed Stalinist government. The Hungarians we met had all seen it and spoke of the Uprising as though it were yesterday. Canada took in almost 38,000 refugees at the time, including some who became distinguished Canadian diplomats.

The Ukraine war has brought both rich and poor Ukrainian refugees to Bucharest, Belgrade and Budapest. There are also recently arrived young Russian men avoiding Putin’s draft. The rich drive their Mercedes and BMWs and have pushed up the rates for luxury flats. The poor have had a similar effect on housing. In Romania, our guide told us the EU pays 15 Euros a day to house the dispossessed Ukrainians, to the disgruntlement of local students searching for cheap housing but, as our various guides pointed out, many of the Ukrainians have since gone home.

It had been nearly 50 years since I’d last back-packed as a student through what was then Yugoslavia. What struck me then was its friendliness and ethnic and religious diversity. The old ladies on the train from Zagreb who fed me and shared their wine. The Muslim boy in Sarajevo who gave me abode for the night – his father was a judge – and then hiking with his redheaded Orthodox girlfriend. The Catholic doctor who took me with his young family to Dubrovnik and its splendid beaches.

That harmony was disrupted by the commodified hatreds of Milošević’s rampage of power consolidation. The ravages, losses and lasting effects of that period are, for most people we met, still a firsthand experience. One legacy of the war is a cautious reserve and wariness about active politics. But disengagement from civic life is not necessarily a good thing. Democracy is still nascent in the Balkans. Elections alone do not a democracy make. The Balkans should be a priority for Canada’s promised ‘protecting democracy’ initiative.

Winston Churchill is said to have observed that the Balkans produce more history than they can consume. While other places, including nearby Russia and Ukraine, have been producing much of the history recently, the essence of that observation remains true.

Hungarians, Romanians, Serbs, Croats, and Bulgarians — the Balkan people along our Danube route — all bear generational animosities over ancient grudges and modern grievances that lurk beneath the otherwise sophisticated exteriors of all, including millennials. Few conversations last longer than five minutes without a mention of war, past or present. Their history, geography and demography are such that hard power will always matter. NATO provides for their collective security but in the ongoing contest for hearts and minds, we also need soft power, statecraft and diplomacy.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is Senior Advisor and Fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa. Policy Dispatches are pieces combining travel, policy and political writing from foreign datelines.