Patching the Leaky Boat of the COP Process

While COP26 could have been a diplomatic disaster and wasn’t, the world is still not where it needs to be in emissions reductions to hold the planet to a temperature increase no greater than 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels. The major interlocutors in Glasgow argued that we will get there before the decade is out. Former Canadian Green Party Leader Elizabeth May expresses her impatience, and her belief that the COP process is still the best mechanism we have to get there.

Elizabeth May

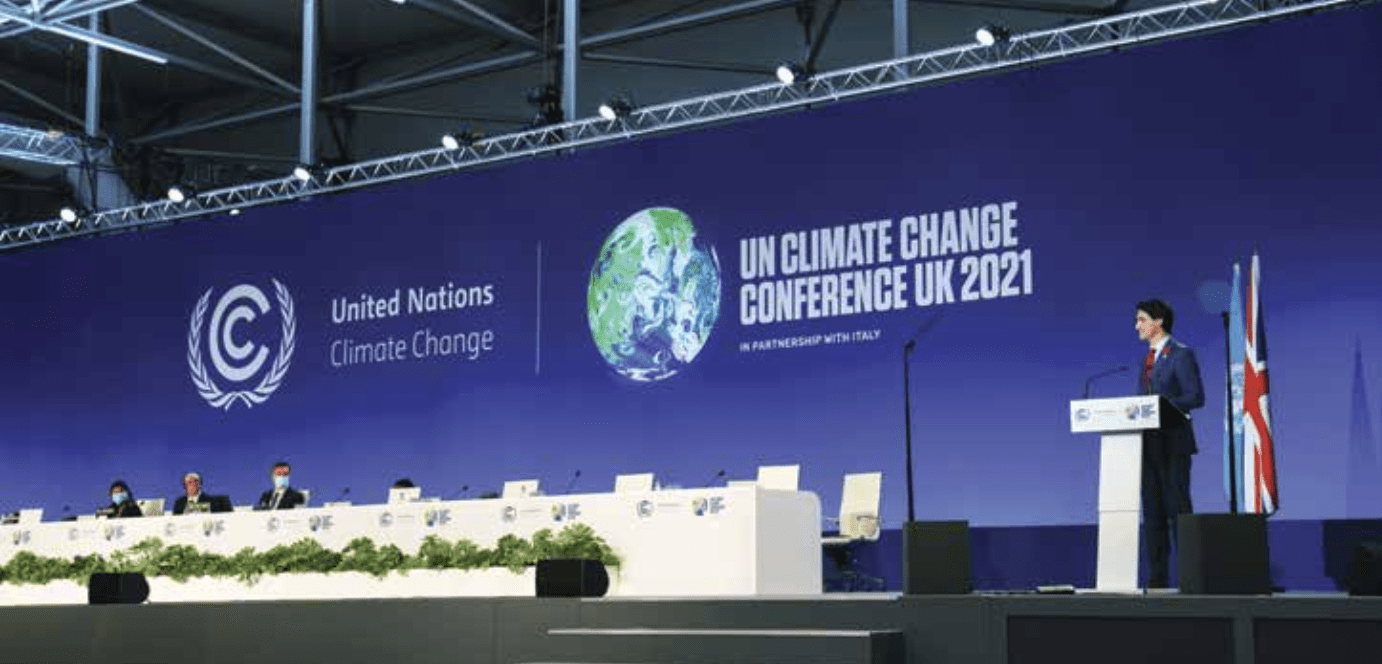

The frenzied activity of COP26 ended with a whimper. There was no cheering; no sounds of champagne corks popping, unless it was in the suites where the 500 fossil fuel lobbyists were holed up.

The results were virtually universally acknowledged to be disappointing.

We went in to the Conference of the Parties (COP26) knowing the commitments – or NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) – from countries around the world, even if fully met, would shoot us well past the Paris Agreement goal of holding to less than 1.5 degrees C global average temperature increase.

To hold to 1.5 degrees, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has made it screamingly clear that carbon dioxide levels globally must be 45 percent reduced below 2010 levels by 2030. For 1.5 to stay in reach, in the first few days of COP26 at the Leaders Summit, heads of government would have had to significantly improve their NDCs. When the high-flying speeches were over, and the leaders headed home leaving ministers and negotiators behind, it was clear that we were still nowhere near 1.5 degrees. The updated synthesis report from the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) confirmed mid-week, that new promises, if met, would lead to 13.7 percent higher global emissions in 2030 than in 2010. Before COP26 opened, the projections showed a 16 percent increase. We have shaved a small amount from the deeply dangerous overshoot.

Still, COP26 may represent a turning point. The final plenary was nearly free of false celebrations and self-congratulatory adulation. If anything, I heard a resolve from many nations that the work must continue non-stop right up to the next COP in Egypt to get the necessary commitments to hold to 1.5 degrees. The sense that hope is still alive must be nurtured. As UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said: “1.5 degrees is on life-support.” But that means it still lives – barely.

The final decision from COP26 includes many elements that have been absent in previous meetings. The language is far more imbued with urgency. Believe it or not, for the first time, the IPCC is invited to present at the next COP. It is also the first text to name fossil fuels as the culprit and to specifically call for phasing-down coal. Of course, based on pushback from China and India, that language was a climb down from the penultimate draft, which had called for coal to be “phased-out.”

Still, we know that time is running out if we are to hang on to a livable climate. We do not have time for incremental improvements.

That point was underscored by the unfolding disasters in my home province of British Columbia even as the final COP text was in intense negotiation. Mudslides, flooding and tragedy were occurring in many of the same First Nations communities, same rural and remote areas of B.C. that had been hammered by the heat dome, wildfires and hellish conditions of an unprecedented summer.

A week after COP, Canada’s Commissioner of Environment and Sustainable Development, Jerry DeMarco released a report detailing 30 years of failure in Canada’s response to the climate crisis. All of our G7 partners and the nations of the European continent have far better records than does Canada. Yet, the world as a whole has not reduced emissions. The horror of it is that from the point when the world community first started to act on the climate issue, dating from 1990 and the launch of work to develop the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), until now, humanity has emitted more Greenhouse Gases (GHG) than we did between the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and 1990. It is not only a record of failure; it risks being a suicide pact.

In his report, DeMarco highlighted lessons learned from this record of failure. Top of the list was the need for leadership. That brought to mind the critical role of leadership when Canada succeeded in solving critical environmental threats- whether acid rain or the threat to the ozone layer.

I had the great good fortune of being in the office of the minister of Environment through those days of success after success. Key to getting the province of B.C. to arrest logging in the extraordinary wilderness that is now Gwaii Haanas National Park, key to getting the US to agree to curb its sulphur dioxide emissions causing acid rain, and key to getting the world to agree to eliminate chlorofluorocarbons that were destroying the ozone layer was leadership.

In all of those cases the leadership was that of the prime minister of the day, Brian Mulroney. From the top-down, the government, its civil servants and its parliamentarians understood that these were priorities that could and must be met. From acid rain to the ozone layer, from the Montreal Protocol in 1987 to the Earth Summit at Rio in 1992, Canada was a world leader on the environment. The Acid Rain Accord of 1991 was the result of seven years of bilateral talks and negotiations between Mulroney and US Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. The Montreal Protocol, signed by every UN member, ended ozone depletion. In other words, the sky stopped falling. At Rio, led by Environment Minister Jean Charest, Canada was an early advocate of sustainable development.

In recent years on climate change, the same can be seen in the governments with spectacular records — whether the UK, Germany, France or Denmark. They have put in place long-term goals that transcend partisan whiplash. Leadership had continuity.

Now, I worry that the process of multilateral negotiations within the United Nations itself may be repudiated. That would be very convenient for the fossil fuel lobby. There is no doubt that Greta Thunberg’s critique resonates. The speeches did have an overwhelming component of “blah, blah, blah.” But the truth is there is no other forum that could possibly engage the whole world in finding climate solutions.

While COPs disappoint, attacking the process itself is unhelpful. True, COPs may be a leaky boat in a storm. It is better to patch the boat and keep baling than to jump into the waves.

It is appropriate to ask how is it that this same UN process that succeeded in saving the ozone layer has stalled and sputtered in dealing with climate.

It is certainly true that the climate crisis engages virtually all human activities. So much economic activity involves fossil fuels or clearing forests. The chemicals destroying the ozone layer involved a broad range – from refrigeration, to propellants for consumer goods and medications to the manufacture of Styrofoam and other products. Still, those chemicals were less ubiquitous.

But I think there is another very significant difference into why one agreement, the 1987 Montreal Protocol on ozone, was effective, and another, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol on climate, was not. The Montreal Protocol included effective enforcement mechanisms in the form of trade sanctions. The Kyoto Protocol did not.

The end of the Uruguay round and the establishment of the World Trade Organization, even without a single decision being issued, led to climate negotiators being deprived of key tools.

So, as we face a vanishingly small window to hold to 1.5, we need to re-examine these global agreements, look at lessons learned and put climate at the top of global priorities. Just as in the ongoing COVID pandemic, we need global collaboration, relying on the science. Trade rules must be brought to heel to support global climate action.

And as in all things, all we lack is political will and leadership.

Contributing Writer Elizabeth May, Member of Parliament for Saanich-Gulf Islands, is the former Leader of the Green Party of Canada. With COP26 in Glasgow she has now attended 12 global conferences on climate change.