Out of Hiroshima: Takeaways from the 2023 G7

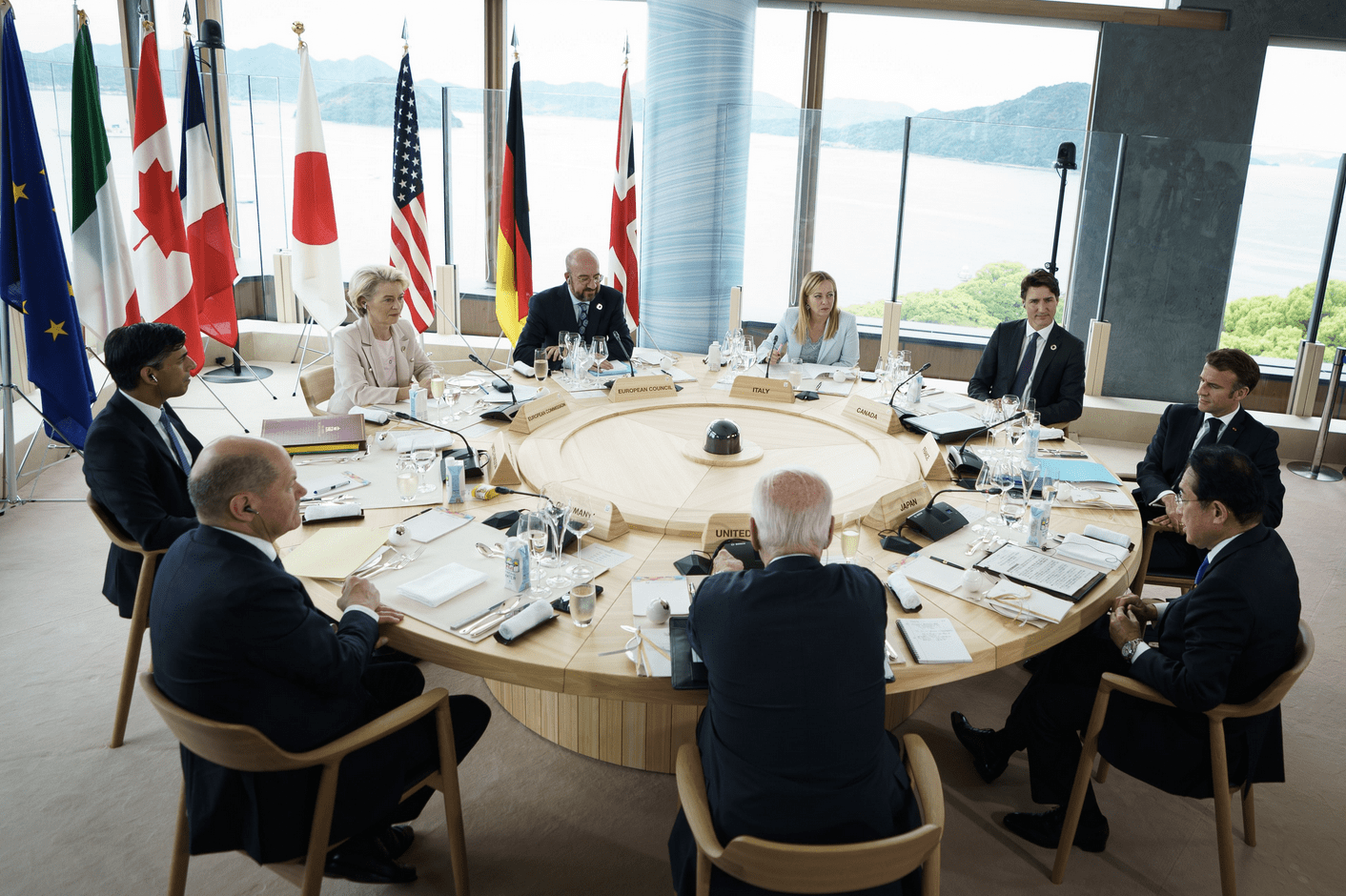

The G7 leaders meeting in Hiroshima, May 19, 2023/Adam Scotti

The G7 leaders meeting in Hiroshima, May 19, 2023/Adam Scotti

Colin Robertson

May 22, 2023

The G7 leaders met this past weekend in Hiroshima and, in an impressive demonstration of solidarity, agreed to a common approach to tackling Russia, China, economic security and many other significant challenges of our day.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, who flew in on a jet provided by France for the final day, secured the leaders’ commitment to ‘support Ukraine for as long as it takes.’ In addition to promises of more arms and money, President Joe Biden said the US would provide training for pilots to operate F-16s.

New sanctions were applied to Russia aimed at hampering its military-industrial defence base. There are additional bans on transfers of western technology and services. The aim is to stop the circumvention and evasion of sanctions and to crack down on the Russian energy and extractive capabilities that are funding Russia’s war.

On China, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak reflected the position of the group when he said China is “increasingly authoritarian at home and abroad” and posed “the greatest challenge of our age“.

The Leaders’ Communiqué explicitly called out “China’s militarization activities” in the Indo-Pacific and its abuse of human rights in Hong Kong and Tibet, as well as in Xinjiang, “where forced labor is of major concern.” The Leaders also told China “not to conduct interference activities aimed at undermining the security and safety of our communities, the integrity of our democratic institutions and our economic prosperity.”

The economies of the G7 and China are inextricably dependent, with China being the first, second or third-biggest trading partner for every G7 member (China is Canada’s second-largest trading partner, or third when trade with the EU-27 as a whole is included).

Recognizing that it is “necessary to cooperate with China”, the communique rejects “decoupling or turning inwards” but adds that “economic resilience requires de-risking and diversifying.”

The leaders’ separate statement on “Economic Resilience and Economic Security” addresses the “disturbing rise” in the “weaponization of economic vulnerabilities”, and cites “economic coercion” as something that will be countered — a definite reference to China. Leaders agreed to a “coordination platform” to counter that coercion and work with emerging economies.

While vague on how this would work, the aim, spelled out in a recent speech by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, is for affected countries to help each other out by not increasing trade with China at the expense of partners, and by identifying ways to work around any blockages put up by China. The Yellen approach also described ‘friendshoring’ by building reliable and secure critical supply chains, an approach also endorsed by Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland.

The leaders’ separate statement on ‘Economic Resilience and Economic Security’ addresses the ‘disturbing rise’ in the ‘weaponization of economic vulnerabilities’, and cites ‘economic coercion’ as something that will be countered — a definite reference to China.

Supply chains for strategic minerals and semiconductors will be strengthened. So will digital infrastructure to prevent hacking and the stealing of technology. Trade ministers are tasked with curbing “inappropriate transfers” of technology shared through research activities.

Multilateral export controls are back in force, particularly for technologies used in military and intelligence, so as “to counter malicious practices in the digital sphere to protect global value and supply chains from illegitimate influence, espionage, illicit knowledge leakage, and sabotage.” The US, with support from Japan and the Netherlands, has already banned exports of chips and chip technology to China.

In its response to the Hiroshima meeting, China accused the G7 of “smearing and attacking” it, calling on partner countries to “stop ganging up to form exclusive blocs” and “containing and bludgeoning other countries” and, in more classic projection, to avoid becoming accomplices to the US “economic coercion”.

Hiroshima, the home riding of host Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, is, of course, better known as the site of the first atomic bombing in 1945. In their ‘Hiroshima Vision’, the first G7 Leaders’ document to focus on nuclear disarmament, they vowed to achieve “a world without nuclear weapons with undiminished security for all.”

Having prioritized climate, food and energy security and Canada’s capacity in critical minerals, Justin Trudeau’s objectives were contained in the G7 Clean Energy Economy Action Plan and the Hiroshima Action Statement for Resilient Global Food Security. There was explicit recognition that critical minerals are essential to the transition to clean energy. Like other leaders, Trudeau made a series of funding announcements on food and climate security, as well as to support continued monitoring of North Korean weapons of mass destruction and Iran’s nuclear activities. Trudeau also announced the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Cook Islands to underline the government’s commitment to its new Indo-Pacific strategy.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky meeting with prime Minister Justin Trudeau on the sidelines of the Hiroshima G7, May 21, 2023/Adam Scotti

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky meeting with prime Minister Justin Trudeau on the sidelines of the Hiroshima G7, May 21, 2023/Adam Scotti

The G7 Communiqué runs to just over 19,000 words with accompanying statements lifting that word count to 30,000. As with all summit communiqués, mostly assembled over months in advance, it is a dauntingly dense and often turgid read. But what comes through is the policy discussions, deep and comprehensive, covering the waterfront of issues. This is practical multilateralism at work for shared purpose among the democracies.

The G7 — comprising the leaders of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, and the United States — is an annual process of ongoing meetings of officials and ministers on a multitude of issues, that culminates in the annual summit. In addition to the presidents of the European Commission and European Council, in recent years it has included invited partners as well as the heads of the principal multilateral organizations. This year, Japan invited Australia, Brazil, Comoros, Cook Islands, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Republic of Korea.

It’s an organigram far larger than the group in the annual class photos and it makes the G7 a multilateral jamboree whose value goes beyond the set-piece meetings. This year it also included a meeting of the Quad (US, Australia, India and Japan), a trilateral between the US, Japan and Korea as well as multiple bilateral meetings (12 for Trudeau, according to PMO) and pull-asides.

With a rotating chair (Italy will host next year and Canada will host in 2025), its revolving bureaucratic structure can be uneven but it works. After 49 summits (the G7 did not meet in 2020) there is continuity and follow-through in managing shared issues. Given their collective weight, when the G7 reaches a consensus, their decisions influence global direction.

As if to illustrate the alternative, while the G7 met in Hiroshima, the Arab League was counter-programming with the authoritarian spectacle of re-admitted Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad being greeted by his Saudi host, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, with a warm embrace.

But democracy and the democracies remain, as it has been for most of this century, under siege. According to Freedom House, while global freedom declined for the 17th consecutive year, the good news is that the gap between the number of countries that registered overall improvements in political rights and civil liberties and those that registered overall declines for 2022 was the narrowest it has been since that decline began. The Economist’s Democracy Index for 2022 reported that, despite expectations of a post-pandemic rebound, the state of human freedom remained essentially unchanged.

As if to illustrate the alternative, while the G7 met in Hiroshima, the 22-nation Arab League was counter-programming with the authoritarian spectacle of re-admitted Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad being greeted by his Saudi host, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, with a warm embrace. Meanwhile, in Xian, Chinese President Xi Jinping hosted the leaders of five Central Asian nations, underlining Beijing’s growing influence in the region. China is already their largest trading partner and they are all participants in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the massive infrastructure plan launched in 2013 that has expanded China’s economic and political influence, fuelled the decline of democracy in participating countries and prompted the aforementioned references to economic coercion.

To counter the Belt and Road, the G7 last year created its Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment. By 2027 it should mobilize up to $600 billion for projects such as railways, clean energy and telecommunications in developing nations. The addition of partner countries at their summits is a recognition by the G7 that they need to broaden their outreach to the Global South.

Since its creation in 1975 in the wake of the oil shock crisis, the G7 has had two overriding priorities: strengthening the global economy and bolstering the rules-based order. Even if its economic weight has shrunk – where once it accounted for close to 70 percent of global GDP, today it is closer to 40 percent — when it acts collectively and in alignment with NATO on security and the EU on economics, its decisions can influence global norms and outcomes.

While their politics and personalities vary, G7 leadership usually share a commitment to fundamental democratic norms and values, unlike the G20, to which all G7 members belong. While the economic weight of the G20 accounts for almost 80 percent of global GDP, its members are truly disparate, with autocrats outnumbering the democrats.

Face-to-face diplomacy is essential to deal with the various and intersecting global crises: an assertive and often aggressive China; the Russian invasion of Ukraine; conflicts in the Middle East, Asia, Africa and the Americas; climate change; food and energy insecurity aggravated by inflation; more displaced persons than we’ve seen since the Second World War; the potential for more pandemics; and now the uncertainties posed by technological innovation, especially artificial intelligence.

If we are to avoid the worst, as the top diplomatic table for the wealthy democracies, the G7 has its work cut out for it. It is not global government but a collective that represents democratic values that are under assault. Given the times and the intense pressures facing us, complacency is not an option. We need a muscular and robust G7.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.