Opportunity in Crisis: How a Spike in News Demand is Redoubling Media Innovation

The saga of how the fourth industrial revolution has impacted the news business is in no way short of its share of ironies. And while the force-multiplying economic contagion of the COVID-19 pandemic has further culled print newspapers, demand for news and information has boomed. That confluence of factors is already producing useful truths and unexpected outcomes.

Pierre Asselin

Newspaper publishers, who had managed to survive the onslaught of advertising losses over the past few years, had good reason to fear that the COVID-19 pandemic—and the resulting shutdowns—would be a final blow.

For some of them, it turned out to be just that, but for many more, it was also something else. It demonstrated that their transition to a different business model, one that didn’t rely entirely, if at all, on advertising, could be the key to sustainability.

There will still be a heavy price to pay for this crisis. The local news research project at Ryerson’s School of Journalism, the main Canadian source for tracking the changes to the industry, has documented the impact of COVID-19 on a map: Covid Media Impact Map

It finds that 24 community newspapers and two private radio stations closed between March and October. Furthermore, 11 daily newspapers have cut one or more of their print editions. This is not a happy story, but it might be one with more than a silver lining.

“The pandemic has increased the demand for our products when other industries, like travel or restaurants, have seen their markets go up in smoke. It was so much more difficult for them than it was for us,” says Brian Myles, publisher of Montreal’s Le Devoir. “I wouldn’t call it a honeymoon, but people have been rediscovering our content and asking for more. It makes it difficult for us

to complain.”

To John Hinds, CEO of News Media Canada, representing the print and digital media industry, this is somewhat paradoxical: “The real frustration for newspaper publishers is that never has the product been in so much demand, while the economics are so bad. We have all the people reading and sharing the content, but no one paying for it.”

Well, not exactly no one. Le Devoir is one of the few media businesses that hasn’t been eligible for the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), as it didn’t experience a large enough drop in its revenue. “It’s either a blessing or a curse,” says Myles. “But it demonstrates that our subscriber model sheltered us from the storm.”

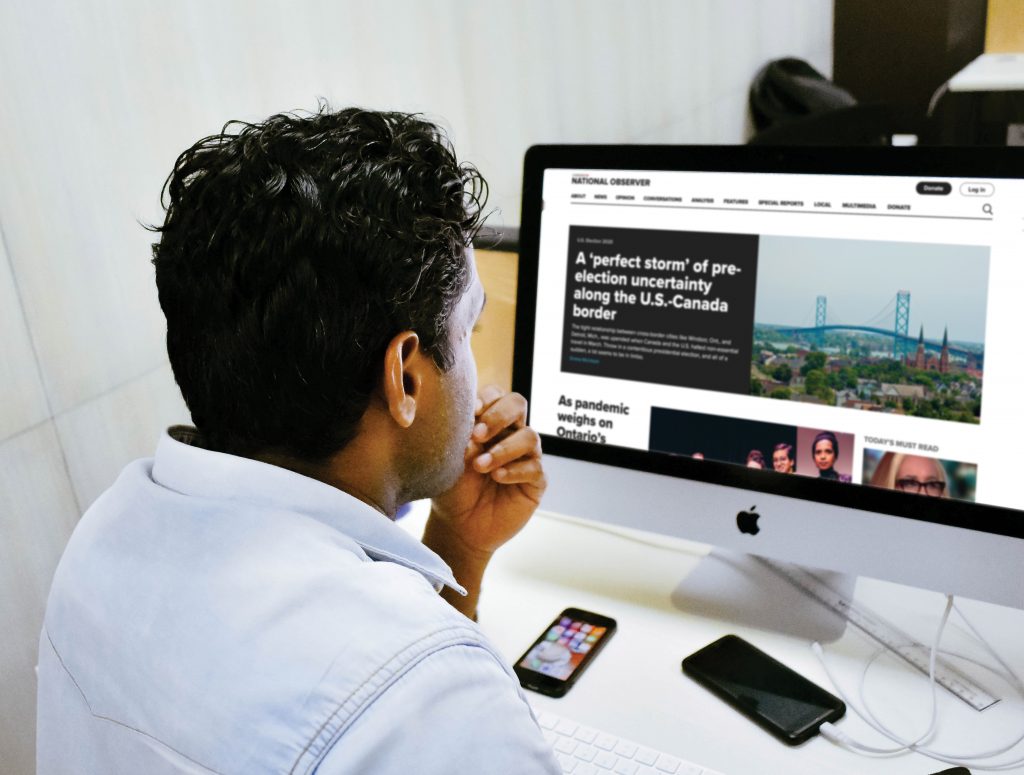

“We do not depend on advertising at all, concurs Linda Solomon Wood, founder of the Vancouver Observer, back in 2009, and now editor-in-chief of Canada’s National Observer, launched in 2015. Advertising has never really been central to us since Facebook came in and started selling ads to businesses here.” explains Solomon Wood. Since 2016, the National Observer has been funded through its paywall. The trade-off between higher traffic and a loyal subscriber base has proven beneficial in the end, because of a strong connection with the readership. “The relationship with the reader is pivotal. We interact as real people, not hiding behind a voice of authority. We share our vulnerabilities and our challenges, and there is a power in that.”

At Quebec City’s Le Soleil (author’s note: where I used to work), the COVID crisis should have been fatal. Capitales Média, a six-newspaper group, had barely survived bankruptcy in August 2019, and transitioned in January to a workers’ co-operative right before the pandemic hit.

But the “Coopérative nationale de l’information indépendante” (CN2i) has survived, thanks to government programs at both federal and provincial levels, and thanks to the Quebec government making the decision to publish its COVID ads in local media rather than global platforms. “It precipitated our complete transition to the digital platform, which was not planned to happen before 2021, after testing our market,” recounts Gilles Carignan, Le Soleil’s general manager. Le Soleil stopped publishing its print edition on weekdays, keeping only its Saturday paper edition. “We had to reduce costs without eliminating any journalism jobs, because we needed them more than ever. We are now a fully digital publisher, with a weekly magazine,” he adds.

In Prince Edward Island, closeness to the community is key to survival. “We are lucky to be in business where we are”, says Paul MacNeill, owner of Island Press Limited, publisher of three weekly papers.

PEI has been relatively spared by the pandemic. “We haven’t laid anyone off, and we hired columnists. Because we’re independent and family-owned, we’re directly accountable only to the community we care about.”

“What we see in this crisis is that people want local news. What they should do, where they can go, what the neighbours are thinking. We’re the only media here, 365 days a year, in Eastern PEI, and in West Prince. Web readership has reached levels we’ve never seen, and remains consistent even this far into the pandemic. The question is, how do you monetize it? Because for us, money is still on the print side…”

But as he also notes: “We’re competing with Facebook and Google, who don’t collect HST. The government must find a model that allows local independents to be sustainable in the long run.”

John Hinds of News Media Canada also believes it. “Google and Facebook use content to drive their business model and pay nothing for it. They take billions out of the local economy. It’s a market failure that needs to be addressed.”

What most media now also understand is that they probably can’t make it alone. They need to work with one another, and partner with other institutions.

This realization is part of what led to the creation of the Institute for Investigative Journalism (IIJ) in 2018, at Concordia University. Its director, Patti Sonntag, wanted to help local media undertake investigative work. Data journalism, she believes, is the ideal tool. “We are putting data in the hands of journalists, and offering practical experience for students before entering into the workforce.”

Canada is lucky to have a vibrant educational system, she adds. “Lots of centres from different universities have been reaching out to media for quite some time. But we’ve also started working together, and it has a tremendous effect. Canadians are really talented at cooperation, right? “.

This kind of partnership allowed the IIJ to set up Project Pandemic, a Canada-wide COVID-19 data resource for small and large news organizations, and in particular for local outlets in rural, remote and Indigenous communities.

“If you strip away all the old industrial costs, running a newsroom isn’t that expensive,” says John Hinds. “Maybe 15 or 20 percent of an old newspaper’s total cost. Everybody sees the future as this lean low-cost operation, but as someone told me, the future is not our problem, it’s the present. How do we get there? We have to get people to pay for news.”

At Le Devoir, Brian Myles insists on the necessity of digital subscriptions. “Elsewhere in the world, the most credible and respected media have relied on this model. These are the ones we want to compare ourselves to.”

Pierre Asselin is a former reporter and editorialist at Le Soleil. He sits on the jury for the Michener Award.