Ontario’s Ford Fiesta: Liberals and Media Didn’t Get It

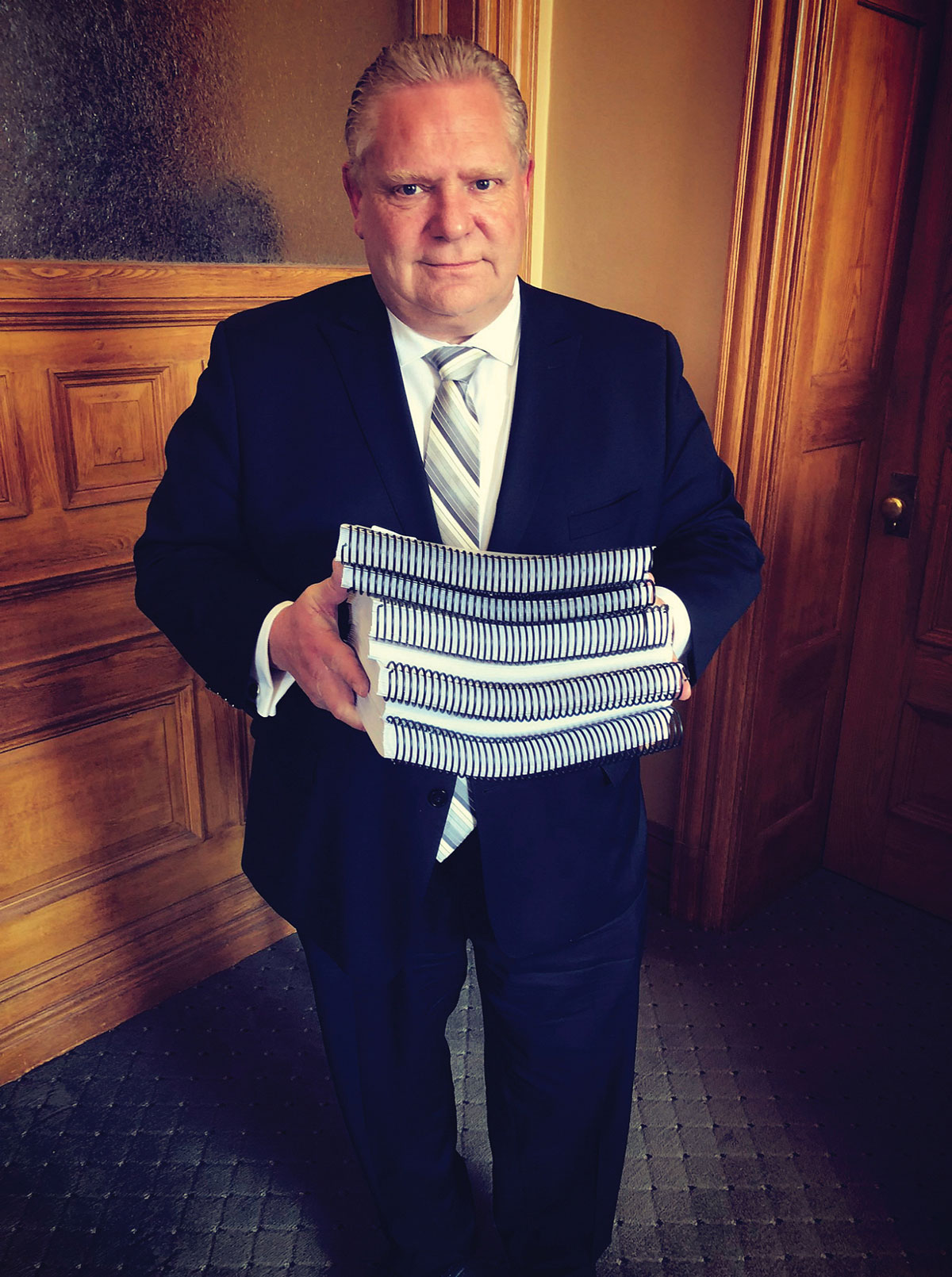

One of the features of democracy’s systemic disruption in the past half-decade has been election-night whiplash, a trend registered in stunning upsets in North America and across the world. Veteran Liberal strategist Patrick Gossage argues that, in the case of Doug Ford’s decisive victory in Ontario, the outcome wasn’t stunning at all.

Patrick Gossage

The “other” Ontario—beyond the smug dominion of Toronto—enthusiastically gave the province a populist government under Doug Ford on June 7th that contrasts greatly with the practical middle-of-the-road governments the province is used to.

What happened? How did the Liberals under Kathleen Wynne so misread the mood of the province? And how could rational people vote for a man who made grandiose promises but never costed them? How could the media have got it so wrong and still be so critical of Ford when the pollsters for once consistently predicted his majority?

The Toronto “elites”, as regular a target in Ford’s ascension as their American equivalents were in Donald Trump’s, ended up almost voiceless in the new government. Liberals were reduced to seven seats, only three in a generally orange NDP Toronto south of the 401. And that includes the Toronto-centric media who Ford treated with disdain at no cost to his popularity.

The media, the Toronto Star particularly, didn’t know what to make of what bureau chief Robert Benzie called Ford’s “improbable” rise to power, calling Ford an “accidental premier”. Ford liked telling his adoring crowds that the media didn’t want him to win. And he did everything to annoy them—not running the usual media bus, taking only a handful of questions daily with an aide handling a microphone to ensure no follow-ups.

When we decided during Pierre Trudeau’s 1980 campaign to vastly limit media availability, as press secretary I learned that voters did not care a bit that the fourth estate was inconvenienced. The Ford election proved that the opinions of traditional media don’t count for much when voters make up their minds.

So, who is the “other” Ontario that rallied to Ford and his promises to make Ontario great again? It took an old Conservative political pro, Jaime Watt, to nail it in his Star column: “There exists a divide in the Ontario of today. On one side, an elite class built of media types, professionals and businesspeople, and academics who control many of the levers of communication. This class exists largely in urban centres like Ottawa and Toronto and agrees on a governing ideology that is fundamentally liberal in character. But the rest of Ontario looks dramatically different. It is a group that is far more blue-collar than the elite class imagines. Their appetite for liberal politics is spotty and their tolerance of political correctness barely exists. And those Ontarians simply do not see themselves reflected in the media landscape.”

This is the Ontario that Kathleen Wynne and her band of basically downtown Toronto aides didn’t get either. John Ibbitson of the Globe and Mail was one of the few commentators who did: “Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne forgot that most voters work in the private, not public, sector. They live in suburbs and they drive to work in cars. Many of them have diplomas rather than degrees. If you disrespect these voters—if you tax them and lecture them and make them feel they are being looked down upon—they wreak their revenge. They made Rob Ford mayor of Toronto. Now they’ve made his brother premier.”

The suburban belt around Toronto of self-made immigrants and striving younger families as well as the farmers, the people who’ve lost manufacturing jobs, even northerners, who feel overlooked by Queen’s Park, found the voice they wanted to hear in the bombastic but savvy Doug Ford who was “for the people.” Wynne, as a friend observed, “sounded like she was addressing Cabinet” in the debates. No, it was the direct, simple, always-on-message Ford whose voice they found sympathetic. He understood their anger and frustrations with Wynne’s Queen’s Park and what she had done to their wallets with Hydro rates particularly. His “Help is on the way” mantra that worked so well for so many voters, of course turned into “Help is here” on election night.

Ford’s promises did not add up and he was harassed by the media and his opponents for poorly thought-out promises, including tax reductions of 20 per cent, Hydro bill reductions of 12 per cent, 10 cents per litre off gasoline, and no serious attention paid to reducing the deficit and provincial debt that Ford loved talking about as the largest of any sub-national government in the world.

Ford’s victory, like Trump’s shows that there are real divisions between different segments of society. Politicians who ignore these divisions do so at their peril. Ford deserves respect for finding a way to appeal to a vast swath of Ontario that felt ignored by the provincial government. Obviously, it’s time for more politicians and media to get out of downtown Ottawa and Toronto.

Contributing writer Patrick Gossage was press secretary to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau from 1976-82, and later head of the public affairs division of the Canadian Embassy in Washington. He is the author of Close to the Charisma: My Years between the Media and Pierre Elliott Trudeau, and founding chairman of Media Profile, a Toronto media consulting and PR firm.