One is No Longer a Lonely Number

By Douglas Porter

October 18, 2024

Saturday marks the 37th anniversary of 1987’s Black Monday, which was the worst single day for U.S. stocks in history, when the S&P 500 fell 20.5% in one session while the Dow cratered by 22.6% on that 19th day of October. For perspective, the worst day during the awful 2008 meltdown was -8.8% in late September. This is not meant to conjure up the dark spirits of the past—let’s save that for the 31st—but rather to remind that this time of year has often been downright scary for markets. Not this year. Almost mocking the challenging seasonal factors, the S&P 500 has climbed more than 3% since the end of August, while the Dow is up 4%, and even the previously laggard TSX has jumped 6%, all to record highs. This sturdy advance has been in the face of rising geopolitical tensions and an oncoming U.S. election that is still very much a source of deep uncertainty.

What explains the market’s sunny ways? The start of Q3 earnings season has been supportive, but stocks have been on a roll for the past year, with the S&P 500 now up more than 40% from last October’s lows. Central bank rate cuts have provided some fuel, revved by the Fed’s outsized 50 bp cut, and responded to this week by the ECB’s third 25 bp slice. But markets have long been pricing in and fully anticipating rate cuts, almost from the time that central banks began the hiking process. A more fundamental supportive factor is simply a better-than-expected set of economic outcomes than expected a year ago. Specifically, the trade-off between lower inflation and softer growth has been much more favourable than anticipated.

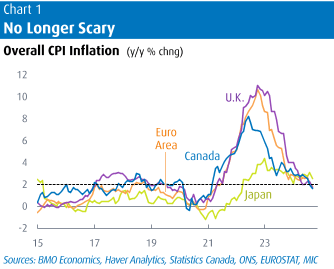

Exactly a year ago, the consensus view among forecasters was that the U.S. economy would slow this year to just over 1% real GDP growth. Instead, it now looks like the economy will grow by nearly 3% in 2024—we have bumped up our estimate to 2.8%, with solid retail sales a prompt—and then hold above 2% in 2025. Has this astonishing resiliency of the economy thwarted the effort to bring down inflation? Not in the least. A year ago, the consensus was that headline U.S. CPI would cool to just under 3% this year before easing to just above 2% next, and that remains exactly the case. In other words, inflation remains nicely on the glidepath back to target—after bolting above 9% to its highest level in more than four decades in mid-2022—with almost no serious damage to growth. It may be fair to say that even the most optimistic Fed official in their happiest state of mind would not have dared hope for such a positive outcome a year or two ago.

It’s true that the inflation/growth tradeoff has not been quite so friendly for every major economy. In fact, the U.S. is a clear outlier on the growth front this year among mature economies. Canada will struggle to keep above 1%, and it may well still be the second-fastest growing economy in the G7, with France and Britain in cold pursuit at around 1%. Italy has reverted to form this year with meagre 0.5% growth, while both Japan and Germany will be about flat—the latter could report a second consecutive year of a small GDP decline. Yet, in fact, few of these mild results are a big surprise from admittedly modest expectations of a year ago. Indeed, Britain and Canada have managed to grow a tad faster than the consensus expected a year ago, while the Euro Area is maybe a tenth better. And, the flip side of the sluggish growth in these major economies outside of the U.S. is that it has triggered a faster-than-expected drop in inflation.

This week brought a flurry of 1-handle readings on headline CPI around the advanced world. Canada kicked things off with a lower-than-expected 1.6% result for September, dropping below the 2% waterline for the first time since early 2021. The U.K. soon echoed with a 1.7%, and the Euro Area in turn matched that result. Notably, these aren’t even the lowest rates, with Sweden at 1.2% and Switzerland at 0.9%. And, buried beneath the Euro Area 1.7% total, there are some members well below that average, with Ireland taking the crown at precisely 0.0% inflation at the moment. Thus, when it comes to inflation, ‘one’ is not the loneliest number, it’s the ‘it’ crowd. Not to be left out, even the U.S. is currently running a 1.6% y/y CPI, when based on a harmonized measure to make it comparable with other economies.

There are of course some major exceptions that prove the rule. Japan, as is so often the case, is running against the grain. After decades of struggling with deflation, it suddenly finds itself atop the CPI leaderboard—even as inflation dipped to 2.5% last month. It’s a rare economy that has seen growth come in a bit weaker than expected this year, and inflation a bit higher than forecast. However, the latter is hardly seen as much of a problem following 30 years of no price increases and a persistent effort to boost inflation. The Nikkei certainly doesn’t seem to mind, as it is up 25% y/y even after a harsh mid-summer swoon. A weaker yen has flattered corporate revenues, and the currency has softened back to around ¥150 in recent days.

The other big exception is China. This week’s wave of economic data was a mixed bag, but reinforced the message of low-low inflation and generally disappointing growth (by China’s standards). Real GDP was on form in Q3 at 4.6% y/y, keeping the economy on track to match our 4.8% expectation for all of 2024 (versus 5.2% last year), and doing little to budge our 4.5% call for 2025. The waves of stimulus measures have essentially just kept us from cutting our forecasts. September data suggest industrial output and retail sales perked up a touch, but trade flows were quite sluggish, weighed by special factors. Meantime, CPI inflation remains a rumour at just 0.4% y/y (with core at a meagre +0.1% y/y), while producer prices are down 2.8% y/y. After a fiery 30%+ rally in stocks from the September low, the CSI 300 has since pulled back, but remains 11% above year-ago levels. The fact is that even China is not completely out of sync with the bigger global picture, with overall growth hanging in and inflation surprising on the low side.

The low-side surprise in Canadian inflation was the trigger we had been waiting for to officially change our call on next week’s Bank of Canada rate decision—we now look for a 50 bp cut to 3.75%. We are sticking with our call that this meeting will be followed by a series of 25 bp cuts, ultimately taking the overnight rate to 2.5% (but now getting there one meeting sooner). Given the Bank’s obvious anxiousness about reviving growth and halting the rise in unemployment, there’s still a risk of even faster easing, and ultimately taking rates even lower (their range for neutral is 2.25%-to-3.25%).

Just a reminder that our call is what we believe the Bank will do, and not necessarily what we think it should do. This is a rare occasion where the two do not completely intersect. As outlined a week ago in this space, there are a variety of good reasons for the Bank to proceed cautiously, not the least of which is the fact that U.S. growth revisions keep going up, coupled with record highs for equity markets—far from signalling financial strain. Meanwhile, fiscal policy is hardly holding growth back, with credible projections that Ottawa will miss its deficit target, both major parties in B.C. promising fiscal goodies ahead of Saturday’s election, and the biggest province rumoured to be about to hand out cash to every Ontarian. And, finally, there is the existential inflation risk hurtling at Canada from that massive event in November that so many have been breathlessly waiting for and could cause economic ruptures—the Globe and Mail reports that tickets for Taylor Swift’s six Toronto concerts next month are running at $2,500, for “resale seats, even with terrible views of the stage”.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.