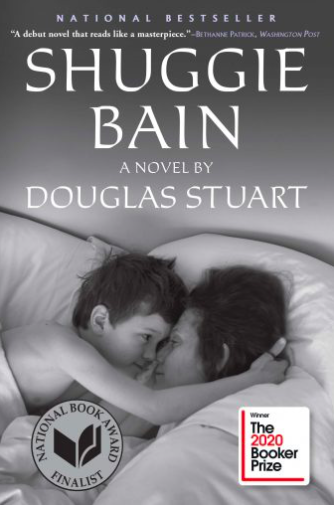

Not for the Faint of Heart: The Love, Brutality and Hope of One Boy’s Glasgow

By Douglas Stuart

Grove Atlantic/October 2020

Reviewed by John Ivison

December 18, 2020

You might imagine Douglas Stuart’s Booker Prize-winning novel about Hugh “Shuggie” Bain, a sensitive boy growing up in a tough housing estate near Glasgow in the 1980s while tending to his alcoholic mother, has no lessons for Canadian policy makers.

You’d be wrong.

The backdrop to Shuggie’s story is the poverty, unemployment and hopelessness of an economy caught in transition and the impact on those all-but-abandoned by the state.

As Shuggie’s cheating, unreliable and largely absent father notices from the front seat of his taxi: “The city was changing, he could see it in people’s faces. Glasgow was losing its purpose, and he could see it all clearly from behind the glass. He could feel it in his takings. He heard them say that Thatcher didn’t want honest workers anymore; her future was technology and nuclear power and private health. Industrial days were over and the bones of the Clyde Shipworks and the Springburn Railways lay about the city like rotted dinosaurs.”

The human ramifications of callous industrial policy are all too apparent in Stuart’s sweeping account of a city in flux, a story loosely based on his own experiences.

It is gripping, utterly authentic and relentlessly grim, as Stuart’s description of the weather encapsulates. “Rain was the natural state of Glasgow. It kept the grass green and the people pale and bronchial.”

This is not the Glasgow of incomparable architecture, foodie quarters and gleaming shopping malls. It is the underbelly of a very different city, riven by sectarianism and hopelessness.

Shuggie, who laments his inability to be “normal”, and his brother Alexander, “Leek”, move into a run-down public housing estate with their mother, Agnes, after their father abandons them.

The estate was built to house miners and their families but the pit has been closed down. “Now in the evenings, the eldest of the miners’ sons stood at the train tracks with beers and bags of glue and watched with sadness and spite the happy faces roar by (on the Glasgow to Edinburgh express) every 30 minutes… They threw bottles of piss at the windows, and when the driver let fly his angry horn, they felt seen by the world, they felt alive.”

The human ramifications of callous industrial policy are all too apparent in Stuart’s sweeping account of a city in flux, a story loosely based on his own experiences.

Agnes, a beautiful and proud woman, models herself on Elizabeth Taylor but she has a fatal weakness for alcohol and often spends all the weekly benefit money on cheap but extra-strong Special Brew lager. She learns the hard way the truth in the warning of a speaker at her AA meeting that the drink she wants so badly is like gasoline, fuelling her demons, burning money, family, career and reputation.

For all her flaws, her youngest son devotes himself to saving her and the deep love between the two is at the heart of the book. “He danced for her stepping side to side and clicking his fingers and missing every beat. When she laughed, he danced harder. He did whatever had caused her to laugh another dozen times till her smile stretched thin and false, and then he searched for the next move that would make her happy.”

On one occasion, Shuggie, who is bullied at school for being different, finds his tormentors watching him dance for his mother through their front window. Agnes tells him to keep dancing. “Just hold your head up high and Gie. It. Laldy” (give it your all) she urges him.

It sparks a realization in Shuggie.

“She was no use at maths homework, and some days you could starve rather than get a hot meal from her, but Shuggie looked at her now and understood this was where she excelled. Every day with the make-up on and her hair done, she climbed out of the grave and held her head high. When she had disgraced herself with drink, she got up the next day, put on her coat, and faced the world. When her belly was empty and her weans were hungry, she did her hair and let the world think otherwise.” Shuggie eventually comes to terms with his mother’s disease and his own sexuality, finding hope for a better future.

This is a book of great tenderness and boundless brutality. It is not for the faint-hearted and is, I suspect, hard to decipher for those not steeped in the dialect of the west of Scotland.

Stuart asks much of his readers. But that is nothing compared to what was demanded of him in order to survive and prosper through such a tumultuous childhood.

John Ivison is a son of Scotland best known as a National Post columnist and impresario of the Ottawa Hogmanay. His book, The Riotous Passions of Robbie Burns, was published in November, 2020.