Not a Campaign for the Ages

While Canadian politics — as evidenced by the shutting out of Maxime Bernier’s neo-populist People’s Party on Oct. 21 — have not quite sunk to the levels of toxicity poisoning democracies elsewhere, the 2019 campaign was still deemed the nastiest in memory by both participants and observers. Veteran Conservative strategist Geoff Norquay explores what went wrong.

Geoff Norquay

To say that the recent election campaign was nasty and excessively personal among the political leaders ranks as the understatement of the year.

Charges of hypocrisy masqueraded as substance while real issues went unaddressed. Justin Trudeau used over-the-top scare tactics against provincial phantoms who were not on the federal ballot. Andrew Scheer responded by calling the prime minister a phony, a fraud and liar, but he created his own problems too. He self-destructed on hot-button social issues, predictably feeding the Liberal fear-machine, then got caught hiding his American citizenship (“no one asked”) after criticizing others in the past for their foreign links.

As the leaders began to act like internet trolls, making Trump-like smears a daily tactic of their campaigns, they devalued themselves and the political process. It was therefore not surprising that a funny thing happened in the polls about 10 days out from October 21—the Liberals and Conservatives both started dropping in public support. After trading miniscule leads back and forth at the 34-36 percentage support level for weeks, the two parties moved steadily down in lockstep to the lower range of 31-32 percent as voting day approached. While support for the Liberals and Conservatives bounced back on October 21, this decline in support was a telling reaction to a snarky, vapid and repellant campaign that offended many voters and fed their political cynicism.

How did this happen?

In a mid-campaign piece for Earnscliffe’s Election Insights, veteran pollster Allan Gregg wrote that when political parties construct the specifics of their respective ballot questions, they are signaling to voters that “I am like you, and I am for you.” That is why the three main parties responded to widespread concerns about the rising cost of living with a host of similar boutique tax cuts and credits pitched to appeal to micro-targeted sub-groups of the population.

In public opinion research Earnscliffe conducted mid-campaign on voters’ reactions to the parties’ promises aimed at the cost of living, at least two-thirds of voters could not even vaguely recall a specific promise that the Liberal, Conservative and NDP leaders had made respecting affordability. Furthermore, when interviewers associated party brand with a specific commitment, the attractiveness and credibility of most promises declined in voter assessments. In other words, voters actually thought less of a promise when they were reminded it came from a specific party.

In public opinion research Earnscliffe conducted mid-campaign on voters’ reactions to the parties’ promises aimed at the cost of living, at least two-thirds of voters could not even vaguely recall a specific promise that the Liberal, Conservative and NDP leaders had made respecting affordability. Furthermore, when interviewers associated party brand with a specific commitment, the attractiveness and credibility of most promises declined in voter assessments. In other words, voters actually thought less of a promise when they were reminded it came from a specific party.

These research results suggest that the flurry of affordability promises became little more than “white noise” in the campaign and moved votes only marginally at best. Identifying this “political promise paradox,” the Earnscliffe researchers commented: “Party brand tends to detract from the appeal of almost every promise, but without making sure people associate the brand with the promise, the promise does little to influence vote.”

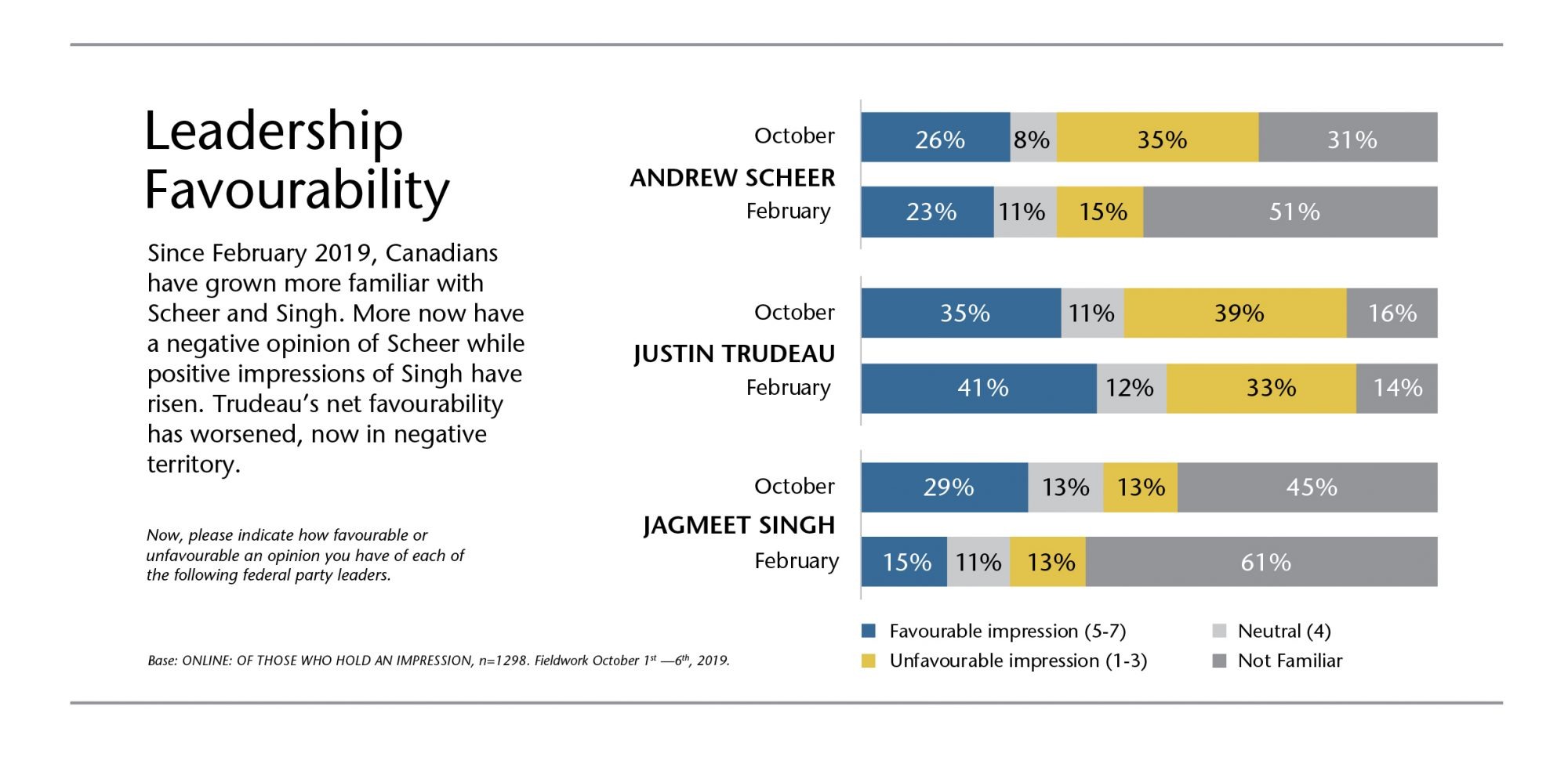

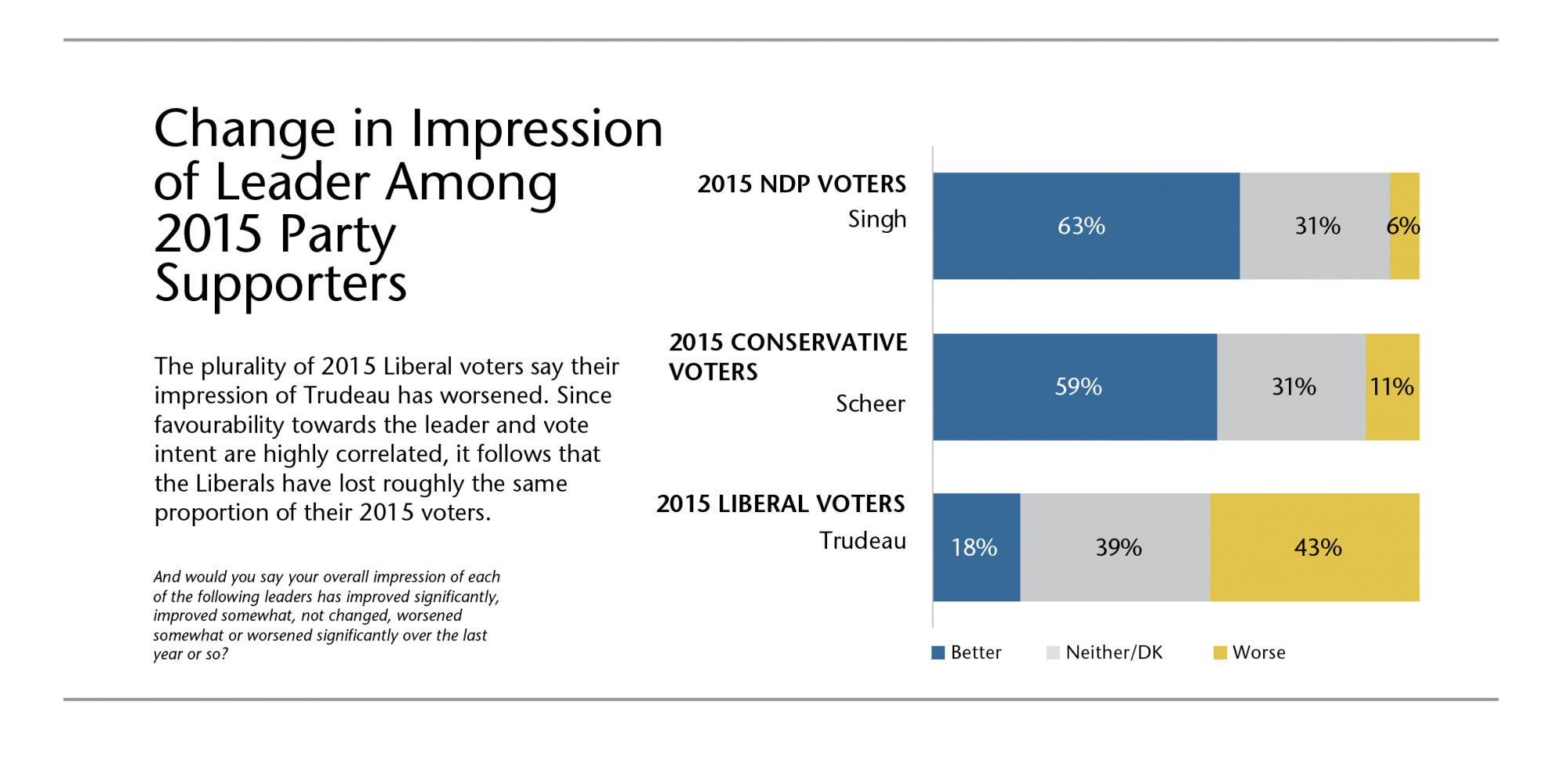

Earnscliffe’s public opinion research also sought to gauge the importance of leadership in building support for parties and determining election outcomes. This research found that impressions of leaders are such a powerful driver of vote consideration for most electors that they relegate all other factors to marginal impact. That said, positive opinions of a leader are a “significant but not sufficient” determining factor in influencing how people will vote, because negative impressions can get in the way.

Favourable opinions of Andrew Scheer rose only marginally between February of this year and mid-campaign, while impressions of Justin Trudeau declined, reflecting his SNC-Lavalin challenges. Jagmeet Singh’s approval rating jumped in the same period as he became better known and voters like what they saw. Interestingly, when the research tested the evolution of favourable impressions of the leaders over the past year, Justin Trudeau was the only leader whose standing among voters had worsened. The fact that Mr. Trudeau ultimately won the election, albeit with a minority, speaks volumes about the strength of his personal brand and that of his party.

When the parties failed to move beyond affordability and differentiate themselves further through innovative ideas to address issues that ran deeper, they left voters seriously wanting more substance. But such challenges as the evolving nature of work, the future of innovation, and protecting privacy in the internet age while strengthening cybersecurity were largely ignored by all parties.

The Liberals hoped the election would be a referendum on their approach to climate change, but the Conservatives ceded that issue in the campaign. With the exception of carbon pricing, the Conservatives had an eminently defensible alternative but they inexplicably refused to engage, leaving the field uncontested to the Liberals and costing them votes in urban areas and among young progressive voters.

While the three top parties fought to a draw on affordability promises, the NDP at least deserves credit for recapturing its policy traditions in 2019. After standing for balanced budgets and losing 51 of their 95 seats in 2015, this time the party reconnected with its base and presented a set of truly democratic socialist alternatives. The party proposed big spending on half a million new child care spaces and affordable homes, universal dental care and interest-free student loans, all financed by borrowing, increases to corporate taxes and a one per cent “super-wealth” tax on people worth more than $20 million. While the party lost 15 of its 39 seats, it can at least claim a moral victory in returning to its policy roots.

While the three top parties fought to a draw on affordability promises, the NDP at least deserves credit for recapturing its policy traditions in 2019. After standing for balanced budgets and losing 51 of their 95 seats in 2015, this time the party reconnected with its base and presented a set of truly democratic socialist alternatives. The party proposed big spending on half a million new child care spaces and affordable homes, universal dental care and interest-free student loans, all financed by borrowing, increases to corporate taxes and a one per cent “super-wealth” tax on people worth more than $20 million. While the party lost 15 of its 39 seats, it can at least claim a moral victory in returning to its policy roots.

Another way to look at the numbers coming out of October 21 is to compare the votes for the various parties in 2019 over the 2015 results. The Liberals received 789,000 fewer votes than in 2015, and the Conservatives increased their support by 540,000 votes. The Bloc Quebecois vote grew by 556,000 this year over 2015, and NDP support plummeted by 623,000.

At 34.4 per cent support, the Conservatives won the popular vote. The Liberals form government with 33.04 per cent nationally, the lowest proportion for a governing party in Canadian history. Due to the distortions of our first-past-the-post electoral system and the efficiency of their vote, the Liberals’ 33 percent enabled them to take 46.45 percent of the seats in Parliament—the most skewed election outcome ever seen in Canada.

These are substantial changes in voter preference, and they left several casualties and difficult issues in their wake. The prime minister inherits a country whose stress fractures were highlighted and exacerbated by the election campaign, presenting some real challenges in managing the federation.

Liberal climate change and pipeline policies were strongly repudiated in Alberta and Saskatchewan, where the governing party won no seats. But polls show 70+ percent of Canadians believe that global warming is a “very big” or “moderately big” problem and 60 percent support carbon pricing. Therefore, Trudeau will not soon be abandoning carbon pricing or withdrawing Bill-69, the new environmental assessment legislation that Jason Kenney has called the “no more pipelines” bill.

After promising in 2015 to patch things up with the provinces, Trudeau faces the reality that 85.4 percent of Canada’s population is now represented by conservative or right-leaning governments at the provincial level, and the prime minister spent the campaign—day in and day out—personally attacking two prominent Conservative premiers by name. His task of forging consensus around common goals among the provinces and territories will be daunting.

Despite chalking up substantial actual and moral victories, Conservative leader Andrew Scheer emerged from the campaign damaged by the widespread belief in his party that given Trudeau’s track record and personal weaknesses, he should have done much, much better on October 21. Scheer can survive next April’s leadership review in Toronto if he starts with a brutally frank post-mortem on the platform, strategies, debate performance and leadership in the campaign. But he must also convince the party faithful he has learned from his mistakes and knows how to do better next time and present a plan for building the party beyond its current limited base.

The strong showing of the Bloc Québécois, which is now a wholly-owned subsidiary of Quebec’s Coalition Avenir government, promises a more strident nationalist voice for that province in national politics. The renewed Bloc presence in the House represents checkmate on the other four parties who should be screaming “foul” against Quebec’s odious Bill 21, which makes a mockery of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

After being all but written off for dead at the start of the campaign and with his party facing a widely-anticipated annihilation by the Greens, NDP leader Jagmeet Singh redeemed himself with an excellent performance. He was user-friendly, passionate and tough but graceful in responding to Trudeau’s blackface embarrassment. He might have saved more NDP seats had he gotten himself into Parliament sooner, but his leadership and standing in his party are now secure.

By any measure, the Green Party campaign was a disaster. Despite advanced billing, the party came nowhere close to challenging the NDP. The mistakes and gaps in its detailed platform caused it to wilt under media and expert scrutiny. The election of only one additional MP was a crushing blow to Elizabeth May and likely means, as she has herself indicated, that this was her last rodeo as leader.

In the end, the strategic and policy choices made by the leaders and their parties could not raise this campaign above the tactical level of a schoolyard ruckus. Canadians can only hope that they can bring more judgment, grace and creativity to the table in governing the country.

Contributing Writer Geoff Norquay, a principl of the Earnscliffe Strategy Group, is a former social policy adviser to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and communications director to Stephen Harper in opposition.