North America at the Crossroads: Inward or Outward?

Frank Graves

Attitudes to trade wax and wane as the issue fades in and out of political discourse. We have now entered a moment where debates about trade are occupying centre stage in the political arena.

Attitudes to trade aren’t simply about how to create a more prosperous economy: they also reflect broader cultural orientations to the external world, groups from different racial origins, and attitudes to issues such as climate change. At no moment in recent history has debate about trade received such salience. This prominence has produced deep fractures in advanced Western societies where trade is connected to deeper social choices as to whether to pursue a more open or more closed society.

The winds of populism have fuelled shocking political disruptions in Brexit and the election of Donald Trump to president in United States. These forces are very much in play in Canada and connected to fundamental tensions which may usher in a new era.

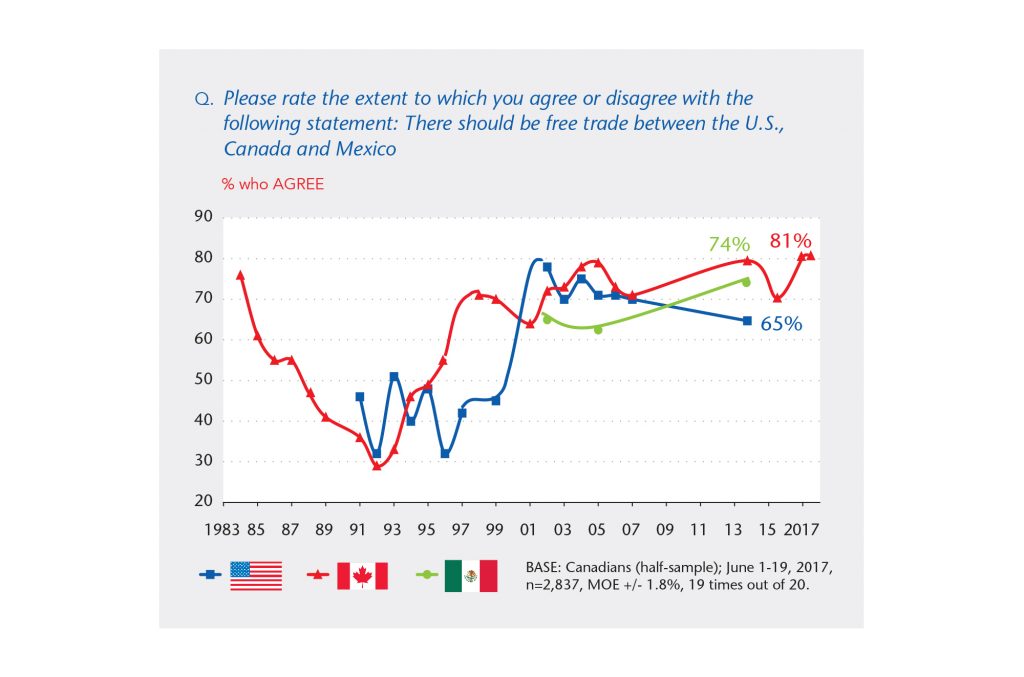

Let’s consider the evolution of public opinion on trade over the past 30 years in Canada, the United States, and Mexico, with a particular focus on Canada. This can be summarized in three key moments:

1) The first moment is defined by a consensus approach in the nervous 90s as the debate about FTA and then NAFTA ensued. Indeed, there was pretty staunch opposition to trade in both Canada and the United States. Despite this, however, FTA and NAFTA were signed.

2) The second moment really becomes clear at the conclusion of the 20th century. At this time, we had pretty well consensual support for trade liberalization, which had been viewed with deep suspicion at the beginning of the decade. The world was now ‘flat’, the end of history had been proclaimed, and business cycles would no longer plague our economies which would be floated on an infinite cloud of prosperity fuelled by globalization, trade, and information technology. Canadians saw themselves as the new Phoenicians. This moment, of course, came under pressure and we saw fairly significant shifts in attitudes as we entered the 21st century and, in particular, the aftermath of September 11th which saw a steep rise in the sense that the world was not merely an oyster, but a source of dread and danger. We found that this frightened outlook on the world has only become more pronounced; in our last poll, we found that only three per cent of Canadians think the world has become safer over the past decade when, in fact, that is probably the right answer.

3) The third moment of public opinion, which has not yet clearly revealed itself, has seen a new age of uncertainty and perhaps an age of disruption which has been fuelled by a protracted period of economic stagnation and rising inequality. This new period has left many citizens of countries such as Britain and United States feeling that they have been abandoned by the bargain of globalization. The white working-class in United States who, in the 80s and 90s, enjoyed middle-class membership on the basis of a strong back and a union card now find themselves in a situation where they have utter hopelessness about the future and smouldering anger about falling out of middle-class.

Although Canada, the United States, and, to some extent, Mexico have moved in lockstep in terms of attitudes to trade, there maybe some emerging patterns of divergence. The rising support for trade in the first decade of NAFTA may not be surprising in light of the near brilliant performance of NAFTA in accelerating the standard of living and economic performance of all three member countries.

The second decade of NAFTA, which occurred in the long shadow of September 11th, saw a NAFTA “gap” which some estimate would be in the neighbourhood of $1 trillion. In other words, if the economies had continued to grow at the same pace as compared to the rather tepid pace that they did in the first decade, another trillion dollars would have been injected into the North American economies.

In this light, it may not be that surprising that the ardour for trade has diminished, as has economic performance, particularly for average workers. The surprising and disruptive impacts of both Brexit and the Donald Trump have yet to be fully revealed, but these are nonetheless fundamental shocks to the system which we will need to watch closely. It may be that although North American countries have worked in lockstep in attitudes to trade over the past 30 years, this maybe now be diverging.

Our most recent Canadian data show that support for trade is at an all-time high. Canadians flirted with the “Closing of the Canadian Mind”, characterized by diminishing support for not only trade but for immigration and for foreign direct investment as well. However, this flirtation with heightened allergy to trade appears to have been ephemeral. Canadians seem to be opting for a more open approach, particularly with respect to trade, which has now reached an apex at the very moment where it appears to be in decline in United States. Our data showed a decline in support for trade in Canada from 2005 to 2013, while a comparable PEW study shows this slide may be continuing in the United States.

It is notable that even though there has been a decline in support for trade, there is still a substantial majority in the United States that supports trade liberalization. If this is true, we urgently need to update these (and related) numbers to provide a fuller picture of where American society wants to go. It may well be the case that support for trade in United States is much more resilient than one would imagine given the narrative of the president or the Lou Dobbs type of commentariat. Nonetheless, it remains likely that Canada and United States are now moving along different trajectories on issues of trade liberalization and on the broader question of the degree to which they want to pursue open versus closed societies.

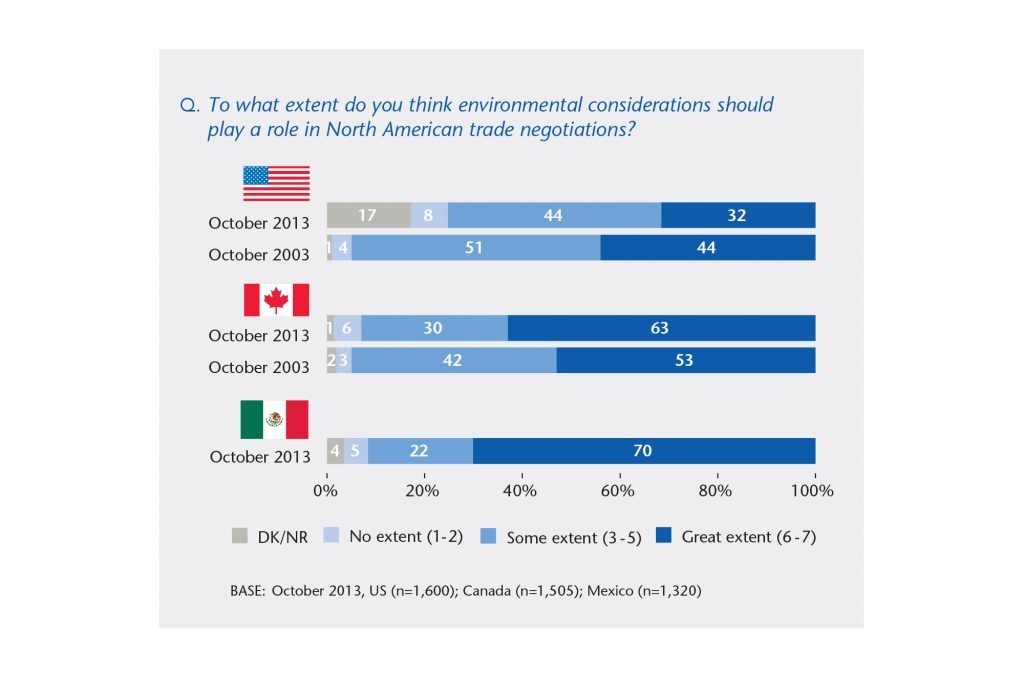

Some of our most recent data now three years old but still relevant suggest that we will be seeing some fundamental contradictions in the way Canadians and Americans want to approach the renewal of NAFTA. Putting aside pretty vivid differences in terms of the positions laid out by the respective governments, with Canada endorsing a so-called progressive vision which includes things like strengthening labour standards, heightened attention to the environment, easier movement of professionals throughout North America, greater access to public markets, and the maintenance of both the dispute mechanism and commitment to supply management. This approach appears to fly in the face an American desire to see greater protectionism, and little concern for environmental and labour issues. The Americans have also identified supply management and want the NAFTA dispute resolution mechanism abandoned.

The degree to which public opinion in the United States supports this approach is unclear and urgently needs updating. We could judge from a few years ago using, for example, the environment, where Canadian and Mexican publics put much stronger emphasis on environment being included in trade agreements, whereas the American public put less emphasis, which was dropping even further. These deepening divisions about the environment underline the challenge of coming up with a common vision about how to retool North America.

Another issue would be the relative role of Mexico. Some feel that in this new era, a bilateral U.S.-Canada approach would make more sense and public opinion does suggest that Americans have more favourable attitudes to trading with Canada than with Mexico. On the other hand, Mexico and Canada reveal great reciprocal sympathies for each other, probably a closer alignment on some of the key policy positions around environment, energy, and security. We should also not ignore the fact that some have pegged the Mexican economy as being the fifth largest economy in the world by 2050. It is possible that a renewed interest in a more muscular North America might be something which could re-establish itself, but it may also be the case that a strengthened North America falls by the wayside as a by-product of this period of disruption and nativism.

In conclusion, we are in a period where trade has been vaulted to centre-stage as a consequence of the rise of populism and age of disruption. We are seeing fundamental questions about whether we want to pursue open or closed societies. This new outlook looks sharply different from the exuberant support for globalization and trade which accompanied the conclusion of the 20th century in upper North America. The winds of change have been fuelled by populism which, in itself, most likely linked to a period of protracted economic stagnation, the end of progress, and the crisis of the middle class, which is operating very much in similar terms in Canada and the United States.

It also appears that although Canada and the United States have worked in relative lockstep on attitudes to trade, we may now be seeing the emergence of a period of sharp divergence. We also note that there may be formidable, perhaps irreconcilable differences in the basic vision of trade and the economy for the future laid out by the current NAFTA partners.

This debate about trade, while critically important in itself, is not just about trade. It is fundamentally linked to some of the more basic questions about what kind of country we want to hand off to future generations. Will we live in a society which is more open or closed to the world? This is not just about trade, but also issues connected to nativism, populism, and xenophobia versus a more open and cosmopolitanism stance. Canada has been buffeted by populist forces which we saw playing out in Brexit with President Trump’s victory.

Finally, in a Canada which appears increasingly to have two fundamentally irreconcilable visions of the future (the conservative and progressive visions), the area of open trade provides an important area of societal consensus in this new age division. For that reason alone, it may be doubly important for Canada to insist on its path forward to be pursuing a more staunch commitment to trade in particular and, more generally, an open—not closed—society.

Contributing writer Frank Graves is President and CEO of EKOS Research, a national public opinion research firm. fgraves@ekos.com

SaveSave