Neighbours, Friends, Brothers in Arms: Tim Cook’s ‘The Good Allies’

Penguin Random House/September 2024

Reviewed by Anthony Wilson-Smith

September 12, 2024

Picture this: at a time when several large countries around the world are behaving in an increasingly belligerent manner, Canada’s military is under-equipped and under-sized. To our north, we are especially vulnerable, a logical potential entry point for enemies. To our south, the United States is beset by bitter internal political divisions – including, most notably, isolationists arguing that the country should stay off the international stage and focus instead on domestic concerns

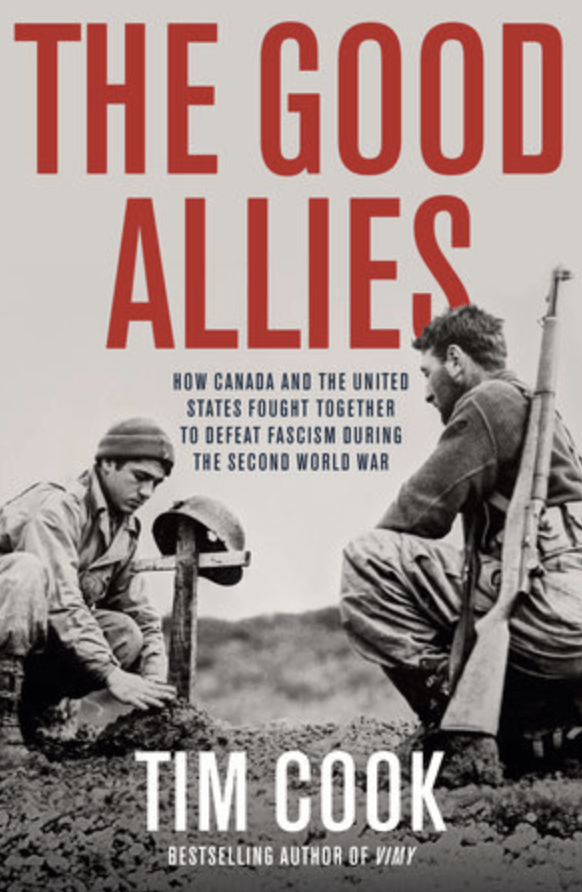

So goes the bleak opening scenario of historian Tim Cook’s latest book, The Good Allies: How Canada and the United States Fought Together to Defeat Fascism During the Second World War. Cook, the chief historian at the Canadian War Museum, and author of a dozen bestselling books, here takes on arguably his most ambitious topic yet – and succeeds brilliantly. The subtitle describes a familiar and welcome outcome with which we’re all familiar — but so many of the steps that led to that end will be, to most Canadians, a surprise. Today, we take our close relationship with the Americans for granted, even though the two countries increasingly move in different directions. As Cook deftly demonstrates, before the start of the last world war, that closeness was far from a given: at various times in the 1930s, senior people in both countries even fretted over the prospect of armed conflict with the other.

In fact, as Cook writes, in 1940, when Canada was formally at war, but the U.S. still neutral, fear of pro-Nazi German-American activists ran so high that Ontario Premier Mitch Hepburn told residents of the province’s Niagara region to prepare to “arm themselves and prepare for a bloody battle to defend ‘their homes and factories, their wives and children.’” He was roundly denounced at home, but Americans, Cook notes, “were more than a little disturbed that the political leader of Canada’s wealthiest and most populous province had accused the US of harboring Nazis for an incursion.”

At the same time, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, personally sympathetic to the Allied side and keen to provide support, was aware that many Americans – including the great aviator Charles Lindbergh – wanted no part of the conflict. By the same token, Prime Minister Mackenzie King had to balance the overwhelming enthusiasm of people in English Canada to support Britain at all costs with pronounced reluctance among French-speaking Quebecers, who still bitterly resented the imposition of conscription at the end of the First World War.

When the Second World War began, Canada was 72 years removed from Confederation – less time than the 79 years that have now passed since the war ended. In our traditions, in the roots of much of the population, and in our outlook on the world, the country was still very much a part of the British Empire, although becoming more ambivalent. King, for whom indecision was often a favoured form of decision, personally reflected both that fondness and a desire for more independence.

The United States was torn in other ways. Its kinship with Great Britain was forged in the First World War, but that still didn’t obscure suspicion of the country from which it had once freed itself. The U.S, seeing itself increasingly able to become the world’s dominant nation, was no great fan of the global reach of the British Empire. Canada, by both accident and design, became a third party drawn into their diplomatic minuet.

In the end, as we know, what united the three countries and other allies mattered far more than the things that divided them. Almost 19,000 Americans served in the Canadian Army, another 9,000 in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

In fact, King’s relative lack of charisma, and suspicion of dramatic actions, masked the shrewdness that eventually made him our country’s longest-serving prime minister. He understood that relations with both Great Britain and the U.S. required collaboration on some issues coupled with deliberate distance on others. He was loyal to England but not to the extent of being subservient. He understood that a close relationship with Washington was increasingly important, militarily and for the economy. But after war broke out in 1939, he also feared – with reason – that if American troops came en masse to Canadian soil to help protect this country, their political leaders might seek to maintain that wartime status quo indefinitely, whether welcomed or not. The creation of the Alaska Highway – running from mainland America through northern Canada, built and paid for by American dollars and people – caused particular anxiety. But in the end, security concerns won out – and it remains an important linkage route today for people of both countries.

King also understood that in his relationship with the charismatic likes of Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Roosevelt, he could push for a seat at the same decision-making tables, but would never be an equal partner. Churchill, Cook notes, disliked King for his cautiousness at the outset, but warmed to some degree as need grew, while Roosevelt cheerfully extended his famous charm as convenient. As King’s trusted adviser, Maj.-Gen. Maurice Pope observed, Canada’s challenge was to be “never in the way, and yet never out of it.”

One of Cook’s many strengths as a military historian is that he equally understands political battlegrounds and the people and tactics involved. Relatively little of this comprehensive (almost 500 pages) book is about the technical strategies of battles fought; rather, he focuses more on the backdrops to them. At the same time, he never loses sight of those who actually fought on the ground, at sea and in the air. As one sign of Canada’s growing independence, he cites a parade ground in England where a British commander one day ordered all the “colonials” in ranks on a training course to “fall out.” The Canadians stood still. After the third repeated and unanswered order, the officer shouted angrily: “Did you hear me ?!?” As Cook writes: “The senior Canadian of the group sharply replied, ‘Yes, but we’re not f—ing Colonials!’”

In the end, as we know, what united the three countries and other allies mattered far more than the things that divided them. Almost 19,000 Americans served in the Canadian Army, another 9,000 in the Royal Canadian Air Force. More than 900 of those Americans died in service of their adopted country. There are no estimates of Canadians who served, in turn, with the American military. But one, Sgt. Charles MacGillivray, of Charlottetown, P.E.I, won the Medal of Honor – the highest American award – for his bravery in action.

One of the great paradoxes of war, as Cook notes, is that alongside its devastating human toll, it is often a great boon to the economies of those on the winning side. The two world wars resulted in great leaps forward for Canada, both politically in gaining independence from Great Britain, and in transforming it into a modern industrial nation. “When we went overseas, for the first time in our lives we felt that we represented Canada,” wrote war veteran Norman Penner. In the aftermath, Cook writes, “Canada carved out its own future, working with the Americans at times and constraining them at others – protecting itself while remaining a good ally.”

The temptation, of course, is to focus on the similarities in the global situation now and the parlous days just before the start of the Second World War. There is no shortage of those, as Cook ably demonstrates. But the real lesson of his remarkably detailed – and wise – overview is that cataclysmic events and their outcomes often result from small interactions and the nature of personal relations. A more decisive prime minister than King, for example, might have welcomed greater American intervention, resulting in a corresponding loss of sovereignty. Or, similarly, have allowed Great Britain to again exert greater influence on Canada as a means of repelling American engagement. King’s one-step-forward-two-back approach charted a middle course, so that Canada emerged from the war more respected – and independent – than ever. Despite what an old saying would have us believe, fortune, in fact, does not always favour the bold.

Contributing Writer Anthony Wilson-Smith is President of Historica Canada and former Editor of Maclean’s magazine.