NATO, Canada, and the Demands of the New Battlefield

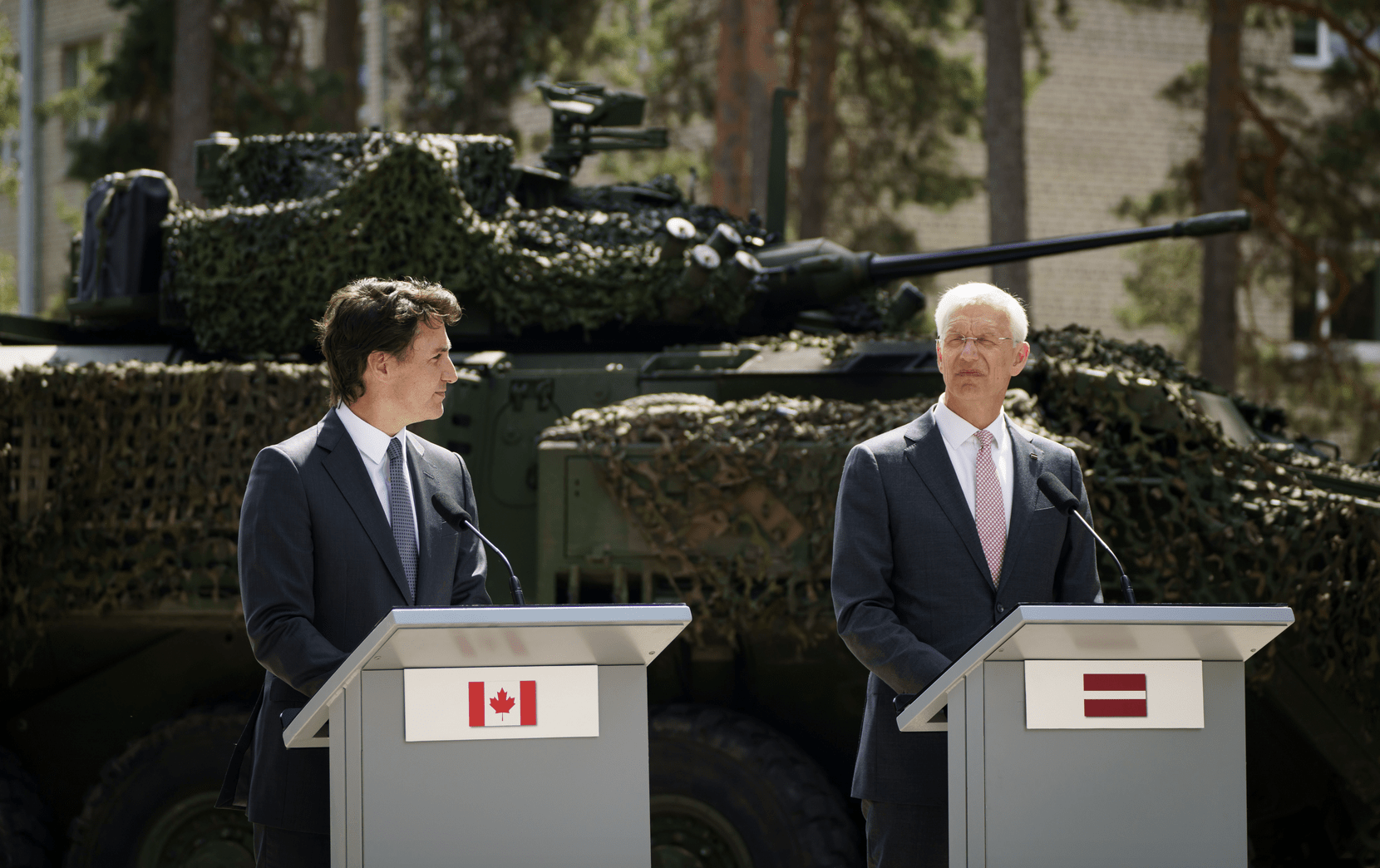

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with then-Latvian Prime Minister Krisjanis Karins at the Adazi Military base in Latvia, where Canada leads a NATO battle group, Monday, July 10, 2023/Adam Scotti

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with then-Latvian Prime Minister Krisjanis Karins at the Adazi Military base in Latvia, where Canada leads a NATO battle group, Monday, July 10, 2023/Adam Scotti

By Elinor Sloan

July 4, 2024

As we approach the July 9-11 NATO 75th anniversary summit in Washington, it is useful to recall that today, as in 1949, Canada’s primary security interest in NATO is to help prevent a general war on the European continent. Such a war, we know, would directly impact Canadian lives and prosperity.

An important part of preventing war is deterrence. Ever since Russia invaded Crimea, NATO has focused on using conventional military capabilities to deter potential Russian aggression against a NATO member. At first, the Alliance chose a tripwire approach. It deployed a small military force to the Baltics with the idea that Russia would be deterred by a recognition of the Article 5 implications of that deployment – that military action against a NATO member along its border would directly impact other members, triggering a larger Allied response.

NATO deployed battle groups to each of the Baltic countries, as well as Poland, with the Latvian one led by Canada. There was no thought that this tripwire force could actually repel Russian military action.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 gave pause to the tripwire approach. Within four months, NATO abandoned it in favor of a combat force that could face off against any potential Russian aggression. It ordered the conversion of the battle groups into full brigades; Canada has committed to transforming the one it leads in Latvia to a multinational brigade by 2026. The combat brigades are meant to be equipped for warfighting. In this regard, the war in Ukraine has given some indicators as to our new conventional military requirements.

Physical mass still matters. Far from the small, high-tech military forces that were at one time seen as the way of the future, the war in Ukraine has revealed that industrial-scale mass has returned to relevancy on the modern battlefield. Traditional combat platforms remain relevant. NATO’s new defence plans indicate the collective defence of Europe demands many familiar things: fighter jets, tanks, artillery, air defence, and long-range missiles. In the Ukraine war, old-fashioned artillery has inflicted the majority of casualties, and fighting without armour has proven costly.

The battlefield has become transparent. Sensors can detect almost any movement, while drones provide continuous battlefield reconnaissance. Forces must be dispersed, constantly on the move, and equipped with digital networks that can connect them across the battlefield and back to headquarters. Technology and access to sensor data enable decision-making at lower levels. Platoon-level forces can see and strike at targets with information that at one time would have been only available at the higher echelons.

Drones are forming an increasingly important and effective complement to traditional military platforms. Ukraine has used thousands of first-person view drones with small payloads to supplement larger artillery barrages against Russian forces. It has crippled Russian air defences by deploying decoy drones that make Russia light up its radars and instantly send targeting data back to larger ground-launched tactical missiles. It has coordinated the use of maritime drones and cruise missiles to take out a large portion of Russia’s Black Sea fleet.

Examples of the electromagnetic spectrum being exploited and blocked in electromagnetic warfare/NATO Joint Air Power Competence Centre

Examples of the electromagnetic spectrum being exploited and blocked in electromagnetic warfare/NATO Joint Air Power Competence Centre

Electronic warfare (EW) remains salient at every high-tech juncture. Advanced sensors, robotics, precision munitions, and battlefield connectivity are all at risk of EW disruption—and are a target of adversary EW disruption—as each side seeks the electromagnetic advantage.

Seeping into all of these elements is artificial intelligence (AI). AI is highlighting the importance of mass and industrial strength – since the ability to pick out thousands of targets points to the necessity of having thousands of weapons to strike them. It is processing and disseminating data to battlefield commanders at superhuman speed, blurring the line between intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance on the one hand, and command and control on the other. And AI is being developed as a solution to EW jamming, by enabling a drone to home-in on its target even if the signal connection to its pilot operator is cut.

The combination of traditional military requirements, cutting-edge technology, and fledgling but advancing AI is creating what some have called a “new kind of industrial war.”

Canada will be challenged to respond to these military requirements. On the personnel side, it struggles to maintain its existing recruitment levels, much less to field a larger force. Our North, Strong and Free, Canada’s defence policy released in April 2024, states a priority of modernizing the Canadian Armed Forces’ recruitment process to rebuild the military by 2032.

In the area of military capabilities, the policy includes acquiring long-range missiles for the Army; modernizing its artillery; upgrading or replacing its tanks and light armoured vehicles; and acquiring both strike drones and counter-drone assets that can neutralize adversary drones. The Army is in the early stages of modernizing its electronic warfare capabilities, as well as acquiring command and control systems at the tactical and operational levels for digital connectivity on the battlefield. The Department of National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces have launched their first Artificial Intelligence Strategy, stating AI will be foundational to defence modernization. Yet they have just begun to identify the AI-enabled capabilities that our military will need.

The challenge with respect to acquiring military capabilities is not so much in securing funding. Rather, it lies in recruiting and retaining personnel with advanced technological skills, and in navigating a defence procurement system which, through the accumulation of bureaucratic steps over many years, is now layers deep and overly time consuming. For good reason, the recent defence policy includes a review of Canada’s defence procurement system.

Ensuring there is no general war on the European continent endures as Canada’s key security interest in NATO. Central to this is credible conventional military deterrence. People and equipment are the core elements. A streamlined, effective personnel recruitment system, and defence procurement process, are the critical enablers.

Elinor Sloan is a Professor of International Relations in the Department of Political Science at Carleton University. She previously served as a defence analyst in the Department of National Defence. Prior to completing her PhD at Tufts University, she was a logistics officer in the Canadian Armed Forces.