NATO at 75: The Alliance Endures

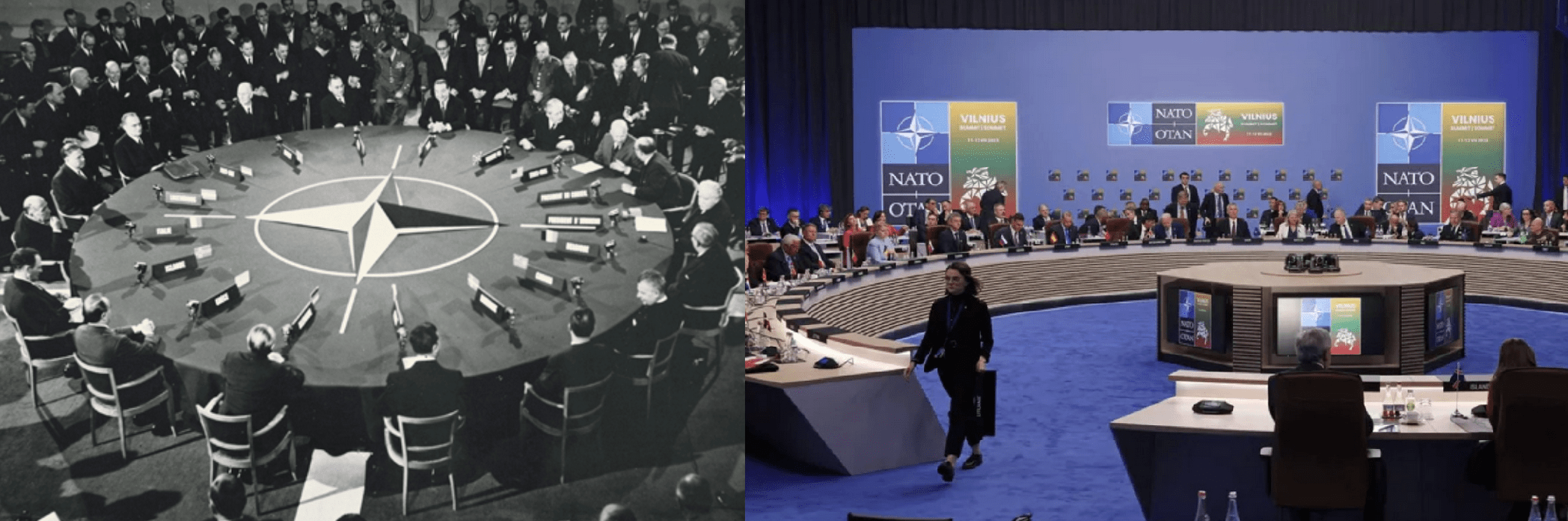

From German rearmament to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO has endured, writes Colin Robertson/NATO archive

From German rearmament to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO has endured, writes Colin Robertson/NATO archive

By Colin Robertson

July 5, 2024

Given ongoing international tensions, the July 9-11 NATO 75th Anniversary Summit in Washington will be less a celebration than a reaffirmation of the continuing relevance and value of collective security.

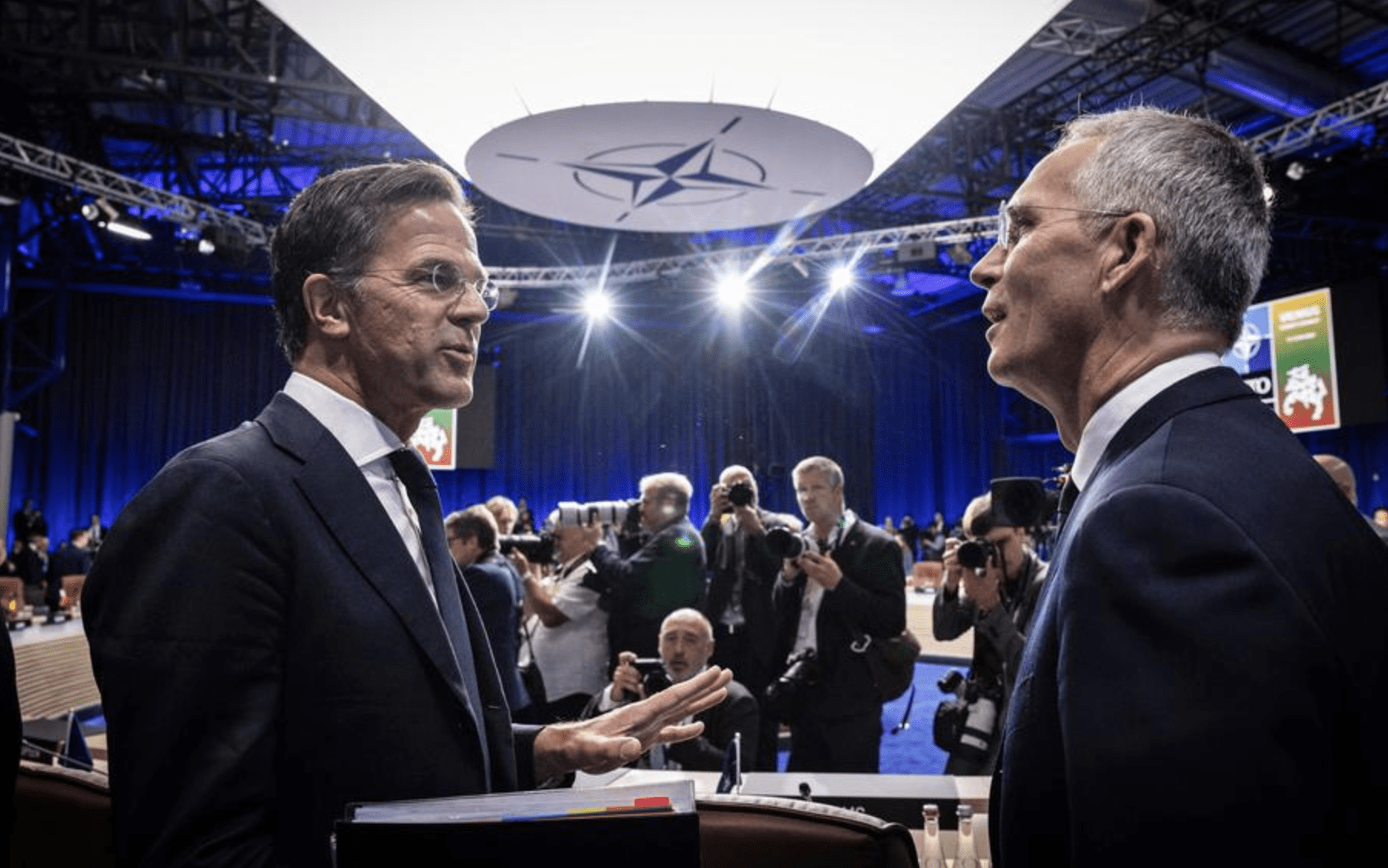

NATO leaders will discuss further support to Ukraine and how to improve alliance readiness and force capacity. They will also welcome incoming Secretary General Mark Rutte who will succeed the extremely able Jens Stoltenberg, retiring in October after a decade of service.

As prime minister of the Netherlands since 2010, Rutte is skilled in managing coalitions, and his diplomacy has already been tested in securing agreement for his nomination from NATO’s 32, often disparate leaders. Now, he must keep the Europeans united and committed to rearmament and the Americans committed to Europe despite the pivot to the Indo-Pacific and the challenge of China.

Inevitably, corridor discussion will revolve around changes caused by the various European elections and the implications of a return of Donald Trump to the White House, especially after Joe Biden’s poor performance in the recent debate. The contrast is stark: a committed Atlanticist, Biden rallied the alliance over Ukraine. Trump disparages allies as freeloaders while claiming he can resolve Ukraine in a matter of days.

For Europeans and Canada, who have relied for 75 years on the US security umbrella, the implications of any American withdrawal or retreat from NATO would be profound. At a minimum, it would ignite debate in Germany, Japan and Korea about acquiring nuclear weapons.

NATO’s 12 founding member states — including Canada — have expanded to 32, adding Finland last year and Sweden in March. Leaders from key ‘partner nations’ – Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand – are now regularly invited to the leaders’ summits, giving the alliance an optic on the Indo-Pacific.

While the path or ‘bridge’ to eventual NATO membership for Ukraine continues to be debated, there is little likelihood leaders would set any definitive date as long as hostilities with Russia continue. Membership amid that ongoing war would invoke NATO’s Article 5, requiring the allies to come to the aid of the attacked member.

Instead, the Washington meetings will continue the ongoing discussions on Ukraine involving NATO’s defence and foreign ministers as well as the G7 and the peace summits, most recently in Bürgenstock, Switzerland. They all have a similar set of objectives: keeping the flow of arms and money to sustain the Ukrainian campaign and to be ready for reconstruction when the hot war ceases.

Secretary General Stoltenberg told Ukrainians during an April visit to Kyiv the alliance is pledged to a “major, multi-year financial commitment”that is “not short term and ad hoc, but long term and predictable” saying that “Moscow must understand: they cannot win. And they cannot wait us out.”

While the process is slower than supporters would like, it is achieving results, including the recent G7 summit decision in Italy, of which Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland was a driving force, to use frozen Russian assets to finance a $50bn loan for Ukraine

Leaders will also take stock of their commitments to rebuild the alliance where, as a recent US Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) report concluded, the allies “have made substantial progress on defense spending, forward defense, high-readiness forces, command and control, collective defense exercises, and integrating Finland and Sweden – achievements which should be recognized in Washington.”

But the CSIS authors also had this caution: “While NATO might be ready for war, the question remains whether it is ready to fight—and thereby deter—a protracted war. To meet this goal, allies still need to spend more, boost industrial capacity, address critical capability gaps, and bolster national resilience.”

Following the Russian invasion in 2022, NATO leaders adopted a strategy of forward defence and deterrence including the goal of meeting the 2% of GDP defence spending by 2024, originally set a decade ago at the Wales summit. According to NATO tracking, 23 allies are expected to meet or exceed the target.

Canada has increased its defence spending with procurements including new jet fighters and warships. The Canadian commitment to NATO includes increasing the Canadian-led battlegroup in Latvia to brigade level, effectively doubling the deployed troops to 2200. As part of Operation Reassurance, the Canadian commitment also contributes ships and submarines, fighter jets and an Air Task Force, providing logistical support.

Incoming NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte (L) and outgoing SG Jens Stoltenberg, at the 2023 NATO Summit in Vilnius/NATO

Incoming NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte (L) and outgoing SG Jens Stoltenberg, at the 2023 NATO Summit in Vilnius/NATO

Canada’s April defence policy update, Our North: Strong and Free, said defence spending is expected to reach 1.76 percent by 2029-30. But the bottom line is we fail to meet both the 2 percent mark as well as the commitment to spend 20 percent on research and development and new equipment.

It prompted a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau from 23 US senators, Democrats and Republicans, expressing that they were “concerned and profoundly disappointed” that “Canada will fail to meet its obligations to the Alliance, to the detriment of all NATO Allies and the free world.” They reflect what our allies’ ambassadors in Ottawa say in their private conversations.

Recent comments by both Defence Minister Bill Blair and Foreign Minister Mélanie Jolie suggest future announcements on the purchase of submarines and NORAD modernization will put Canada beyond the 2% mark.

The Washington summit would be the right occasion for Mr. Trudeau to confirm that Canada will achieve 2%. Some suggest the government should hold off an announcement until after November 5 to allow Trump to claim an early win should he be elected president. But this seems too clever by half.

We should declare our intentions now. Canadian Global Affairs Institute President David Perry recently told the House of Commons National Defence committee, ‘True North’ “falls well short of where we should be in terms of committing resources to defence, because we’re starting from a very low start point, and it also doesn’t change the behaviour that would be needed to actually make use of those resources effectively.” Dr. Perry also pointed out that there is “little indication of how recruiting and enrolling new Canadian troops will be addressed and instead outlines an absurdly long eight-year window to return the Canadian Armed Forces back to its current authorized strength.”

Canada could and should do more in support of NATO. During his recent visit to Ottawa to receive the NATO Association of Canada’s Louis St. Laurent award, Secretary General Stoltenberg recalled his time as Norwegian prime minister, saying it is always easier to spend on housing, health and education but when “we reduce defence spending, when tensions are going down, we must be able to increase spending, investments in our security, when tensions are increasing and are high as they are today.”

Canadians, led by Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent and External Affairs Minister Lester Pearson, were instrumental in the design and creation of NATO especially Article 2 (known as the ‘Canadian Article’), committing members to “strengthening their free institutions” and seeking to “encourage economic collaboration”. Like deterrence and defence itself, these objectives endure.

Before he came to appreciate its value and re-invested in defence, Pierre Trudeau complained that Canadian foreign policy was its defence policy and its defence policy could be summed up in a single phrase: NATO.

While Trudeau exaggerated, for Canadians who had endured two world wars during the first half of the 20th century, anything that would deter a third world war, especially with the advent of the atomic bomb, made sense. NATO was the realpolitik companion to the United Nations.

We were a key partner in creating NATO because a multilateral alliance of democracies based on collective security was the most cost-effective means of ensuring Canadian security and advancing our values. When the Cold War ended, Canada, like other allies, took the peace dividend. But global geopolitics has changed. The world is more dangerous. Now we need to rearm and reinvest in defence.

We should push for, not against, NATO involvement in the Arctic (all Arctic Council members but Russia are NATO members) and more closely align NORAD with NATO. NATO is also the best way to broaden our security partnerships as a hedge against unpredictability in the US.

The public gets it. By a two-to-one margin, Abacus says Canadians want their government “working with allies to promote and defend democracy.” Angus Reid says the percentage of Canadians prioritizing military preparedness has more than doubled over the past decade, while EKOSsays 66 percent say more dollars should be going to defence.

NATO has endured: embracing German rearmament and NATO membership in the 50s; President Charles de Gaulle’s partial French withdrawal in 1966; the placement of intermediate nuclear weapons during the 70s and 80s; the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; interventions in the Balkans (1992-2004), Afghanistan (2001-21), Libya (2011), and now the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

For Canada, NATO represents the two cornerstones of our global policy: the security belt for both our US relationship and our commitment to multilateralism. The arguments for Canada to meet its NATO commitments and to play a leading role in the collective security alliance we helped design remain as valid today as they were in 1949.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.