NATO at 75 and Canada’s New Defence Reality

The 2023 NATO Vilnius Summit/NATO

The 2023 NATO Vilnius Summit/NATO

By Colin Robertson

April 3, 2024

NATO, the longest-enduring alliance of democracies, turns 75 on April 4. The formal celebrations will take place July 9-11 in Washington. The most welcome tribute from Canada would be for Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland to lay out in the April 16 budget Canada’s plan to meet the 2 percent-of-GDP defence spending commitment. The government’s long-promised defence policy update can spell out the specifics.

NATO embodies the two basic pillars of Canada’s global policy: our relationship with the United States and multilateralism. Canada was instrumental in the design and creation of NATO and it remains a cornerstone of our defence and foreign policy. NATO’s Article 2, which commits members to “strengthening their free institutions” and seeking to “encourage economic collaboration”, is known as the ‘Canadian Article’.

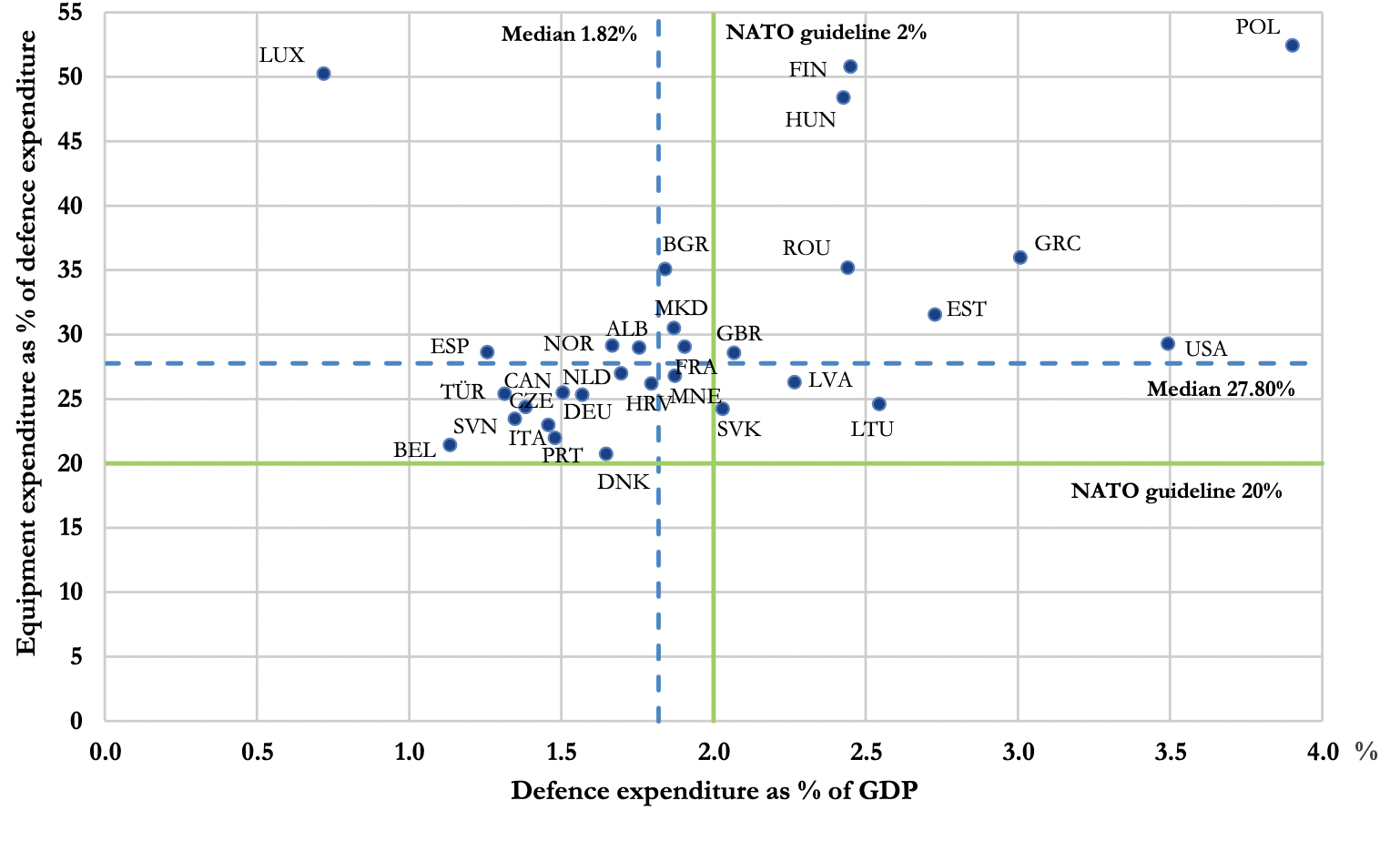

Source: NATO Defence expenditures and NATO’s 2% guideline March, 2024

Today, Canada is alone among the 32 NATO allies in not meeting the 2 percent spending bar and the requirement to spend 20 percent of that expenditure on equipment.

We are, says Chief of Defence Staff Gen. Wayne Eyre, “in a time of profound change”. With Russia and China not differentiating “between peace and war”, the world is “more chaotic and dangerous than at any time since the end of the Cold War”. Eyre, who retires this summer, told members of parliament that Canada’s control of its Arctic is “tenuous” and “there’s just not enough Canadian Forces to be able to do everything.”

The Trudeau government committed significant investments as part of its 2017 defence policy and the 2022 NORAD modernization to pay for new ships and fighter aircraft. But defence preparedness requires more investment in weapons, submarines, defence production, and in our Forces. We also need the kind of creative involvement Canadian leaders demonstrated at NATO’s inception.

The public gets it. By a two-to-one margin Abacus says Canadians want their government “working with allies to promote and defend democracy.” Angus Reid says the percentage of Canadians prioritizing military preparedness has more than doubled over the past decade while EKOS says 66 percent say more dollars should be going to defence.

The public support is there but where is the political will to make it happen? A start would be for the 95 members and senators of our NATO Parliamentary Association to demand action within their respective caucuses.

NATO’s first secretary general, Lord Lionel ‘Pug’ Ismay, famously quipped that NATO was created “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in and the Germans down.”

A defensive alliance, its members were sworn to stand together against aggression. Codified in NATO’s Article 5, an attack against one would be an attack against all. The only time that Article 5 has been invoked was after 9-11. US NATO ambassador Nicholas Burns told me it was Canadian ambassador David Wright who took the lead in mobilizing NATO council members.

NATO’s original fourteen member nations have expanded to 32, adding Finland last year and Sweden in March. Leaders from key ‘partner nations’ – Australia, Japan, Korea and New Zealand – are now regularly invited to the leaders’ summits, giving the Alliance an optic on the Indo-Pacific.

Overall, NATO has succeeded: weathering German rearmament in the 50s; President Charles de Gaulle’s partial French withdrawal in 1966; the placement of intermediate nuclear weapons during the 70s and 80s; the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; interventions in the Balkans (1992-2004), Afghanistan (2001-21), Libya (2011), and now the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

NATO is returning to collective territorial defense. At last year’s Vilnius summit, the leaders’ communique identified the direct threat of Russia and the vital importance of supporting Ukraine, the asymmetric threat of terrorism, and the ‘ambitions and coercive policies’ of China.

National service is enjoying a revival. The Baltics and Nordics are already on board and the Germans and British are now debating it. So should Canada, especially given the crisis facing our Forces in recruitment and retention.

When they meet in Washington this June, the allies will reaffirm the Harmel principles (1967) ensuring defence and deterrence, with confidence-building and cooperation when adversaries demonstrate that they are willing to abide by the basic principles of the UN Charter.

NATO is growing its response force by eightfold and working to establish collaborative defence procurement with resilient supply chains. Canada will continue to lead and double our troops in our enhanced forward-deployment NATO mission in Latvia.

NATO is also revamping its procedures and systems. To help this process, the Alphen Group of strategists has just released its ‘Trans-Atlantic Compact’ with specific capacity benchmarks, metrics and a roadmap. Its recommendations include a European-led NATO Allied Command Operations Heavy Mobile Force consolidating all Allied Rapid Response Forces into one single pool of forces. It would also strengthen operational capacity by combining multidomain conventional forces, missile defenses, nuclear deterrence, space support, cyber defenses, and protection against multi-form hybrid threats.

The way the alliance spends money is problematic, especially when it comes to duplication, readiness, and a lack of deployability. These will be top internal priorities for Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg’s successor as he steps down in October 2024 after 10 years.

Inevitably, the US election and a return of Donald Trump will be the elephant in the room. Here, the contrast between Joe Biden, an Atlanticist to his core who rallied the alliance over Ukraine, could not be more stark with Trump, who looks at alliances as a protection racket.

For Europeans and Canada, who have relied for 75 years on the US security umbrella, the implications of any American withdrawal or retreat from NATO would be profound. At a minimum, it would ignite debate in Germany, Japan and Korea about acquiring nuclear weapons.

European leadership is increasingly convinced, in a way they weren’t before the war, that Russia is a military danger to them. Between Ukraine and Trump, this means more self-reliance and more equitable burden-sharing and arecognition that 2 percent is just a floor. Our allies in Eastern Europe are now spending even more, recognizing the continuing relevance of the Roman adage: “If you want peace, prepare for war.”

This means more defence investments, in line with NATO’s 2030 Agenda. Canada should collaborate with European allies in joint defence production.

National service is enjoying a revival. The Baltics and Nordics are already on board and the Germans and Britishare now debating it. So should Canada, especially given the crisis facing our Forces in recruitment and retention.

After two world wars, Canadian leadership vowed “never again”. We were a key partner in creating NATO because a multilateral alliance of democracies based on collective security was the most cost-effective means of ensuring Canadian security and advancing our values. When the Cold War ended, Canada, like other allies, took the peace dividend. But global geopolitics has changed. The world is more dangerous. Now we need to rearm and reinvest in defence.

We should push for, not against, NATO involvement in the Arctic (all Arctic Council members but Russia are NATO members) and more closely align NORAD with NATO. NATO is also the best way to broaden our security partnerships as a hedge against unpredictability in the US.

The argument for NATO remains as valid today as it was in 1949. Canadian leadership needs to wake up. Complacency is not an option. On April 16, Finance Minister Chyrstia Freeland needs to set forth the plan by which Canada will meet its NATO commitments and actively re-engage in NATO renewal.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.