Myanmar’s Struggle for Democracy

The February 1 military coup in Myanmar — the military’s response to a landslide victory by Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy in November’s election — has created the world’s first major diplomatic challenge of 2021. Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations, Bob Rae, also served as special envoy to Myanmar, reporting in 2018 on the Rohingya crisis now being litigated as genocide before the International Court of Justice. He filed this piece for Policy on the history, current crisis and way forward for Canada on Myanmar.

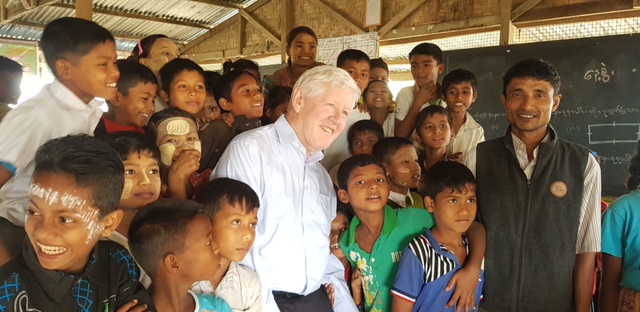

Bob Rae with Rohingya children at Sittwe IDP camp, Myanmar, 2018.

Bob Rae

February 11, 2021

At the end of August, 2017, a simmering conflict between the Rohingya population of northwestern Myanmar and the government of that country came to a head. The narrative of the government and the army (known as the Tatmadaw) was that a number of coordinated terrorist attacks led to a response from the army, and that in light of the conflict, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya farmers and their families fled to safety in southern Bangladesh.

A more accurate account would be that the Tatmadaw was prepared for a fight and used the ragtag attacks from a group known as ARSA as the pretext for a wholesale clearing operation in which thousands of Rohingya were raped and/or killed, and hundreds of villages were destroyed and later bulldozed over. The Rohingya’s trek to Bangladesh on foot, across territory full of land mines, included refuge in hilly, heavily treed territory in the province of Rakhine, where previous generations of their families had retreated in the face of repression.

Before that time, it is safe to say, few Canadians had spent much time thinking about events in Myanmar. A military coup in that country in 1962 had led to decades of repression, not just of minorities such as the Rohingya, but of an entire country. In 1989, Canadians became aware of Aung San Suu Kyi. She was a politician, and the daughter of Aung San, known as the Father of the Nation of modern Myanmar — and, ironically, founder of the Tatmadaw — who was himself assassinated by political opponents on the eve of independence. Aung San Suu Kyi, who was put under house arrest ahead of the 1990 election in which her party won a landslide and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, lived as a political prisoner for 15 out of 21 years. In 2010, she emerged with much fanfare and international support when the Tatmadaw decided to allow her to re-engage politically, and to run for elections under a constitution they had carefully drafted in 2008.

The West supported what they saw as Myanmar’s “transition to democracy”, and, encouraged by Aung San Suu Kyi’s release and her decision to participate in the election of 2015, dropped long-imposed sanctions. In reality, the Myanmar constitution was far from democratic. The Tatmadaw retained control of a bloc of 25 percent of the seats in the Assembly of the Union, or parliament, and of critical ministries and budgets, including Defence, Interior, and the so-called border areas. They were prepared to “share power” with Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, but in reality, the deep state remained very much in their solitary control. Aung San Suu Kyi was not even allowed to assume the presidency — she was disqualified because her children had British passports (a constitutional prohibition customized for her), and while she was free to travel, to assume control of the Foreign Ministry, and to take on a symbolic role, her power and authority were limited.

Myanmar has been in what is, technically, the world’s longest civil war since its independence from the United Kingdom in 1948. The centre of the country, the valley of the famed Irrawaddy River, is home to the Bamar people, whom for centuries have seen themselves as the true Burmese among the country’s 135 recognized ethnic groups. Their Buddhist faith, their language and culture are central to the Burmese national identity. But in the regions to the north, east, south and west live a range of ethnic peoples whose position in the country as full equals has never been accepted by the majority. And, in the area on the border with Bangladesh live the Rohingya Muslims, whose membership in the national club has long been challenged.

The arrests of Aung San Suu Kyi and many other elected officials, as well as artists, civil society activists, and countless others, have been met by a show of resistance that, as of this writing, shows every sign of staying strong.

The 2008 constitution maintained tight rules of citizenship, and the continuing exclusion of the Rohingya remained a source of deep hardship and discrimination that erupted in the recent crackdown, now being described as a genocide in proceedings before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), to which Canada is a party. The opening up of the country to the internet led to an explosion of hatred on Facebook and other social media that populists in the Buddhist clergy, the Tatmadaw, and even parts of the democratic movement were only too glad to whip up.

When the treatment of the Rohingya became an international issue in 2017, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau asked me to serve as his Special Envoy to Myanmar, which led to many trips to Myanmar and Bangladesh, and my report of April, 2018, Tell Them We’re Human. The government accepted my recommendations for a multi-part strategy: listen to the voice of the Rohingya; continue to engage with the government of Myanmar but direct aid not to the government but to civil society; follow the evidence of genocide and insist on accountability; and co-ordinate the responses both within the government and with a number of like-minded countries.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s determination to become an international spokesperson for her country in the face of criticism led to her global reputation falling dramatically, but in fact increased her popularity at home. She hoped to ride this populist wave to increase her power and bargaining room with the army in the election of November 2020, and indeed she won a landslide victory. But the Tatmadaw concluded from her win that their position at the top of the constitutional pyramid was being threatened, and decided that it was time to show their power.

The coup of February 1, 2021 came as a surprise, but it should not have come as a shock. It is hard to de-fang a tiger tooth by tooth. The Tatmadaw was not about to give up without a struggle.

But neither are the people of Myanmar, or those who believe in accountability and the rule of law. The arrests of Aung San Suu Kyi and many other elected officials, as well as artists, civil society activists, and countless others, have been met by a show of resistance that, as of this writing, shows every sign of staying strong. The condemnation of the West was equally forthright. Interestingly enough, even China and Russia agreed to a United Nations Security Council resolution that called for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi and the need to restore constitutional order.

President Joe Biden has announced additional, targeted, sanctions — no doubt other governments, including Canada, will follow. It will be important to ensure that these efforts are focused strongly on those responsible for the coup, and not spread to a general isolation of the country.

Most important, events are showing the resilience and commitment of the people of Myanmar. They do not want to go back to the closed society of the past. But the past few years have shown that even democratic forces need to listen to the voices of minorities that have been left on the margins for too long. It will be critically important that we apply these lessons in the days ahead.

Bob Rae is Canada’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations.