My Fellow Americans: Canada is Worried About the United States

Our dysfunctional democracy is much on the minds of our well-mannered neighbors to the north.

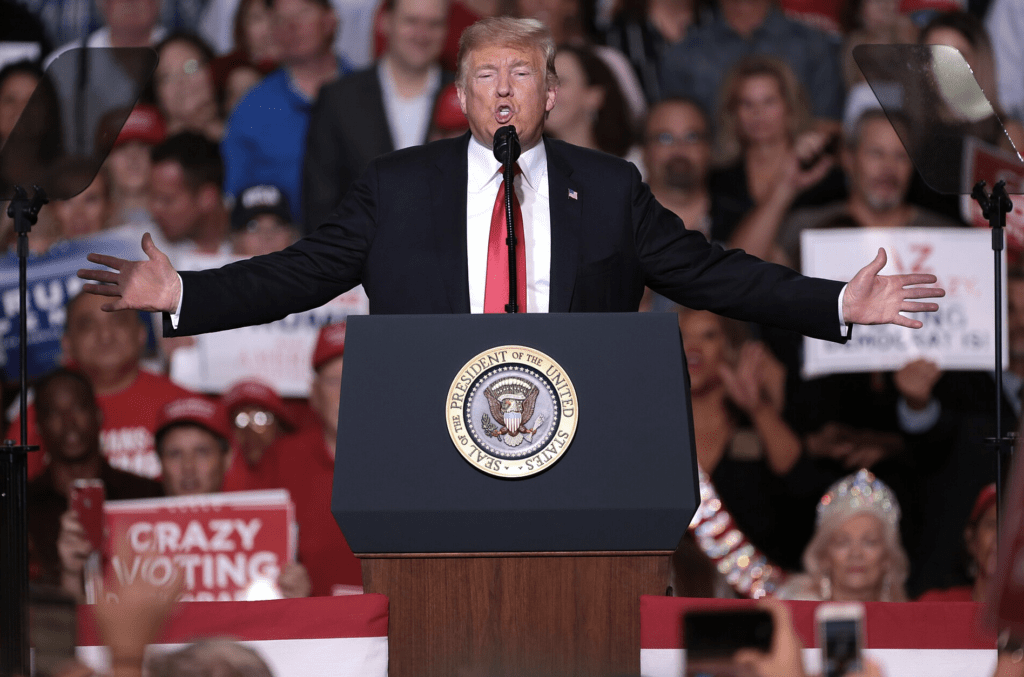

Gage Skidmore

Gage Skidmore

By David Shribman

September 26, 2024

(This piece, first published in The Boston Globe on September 18th, is re-posted with full permission).

MONTREAL—Join me for a nice lunch on a restaurant patio here in Canada, with crispy frites on the menu, beer on tap, and late-summer yellow jackets circling menacingly. Around the table in the September sunshine are both francophones and anglophones, and the conversation slips easily between both of Montreal’s founding tongues. But it stalls on one topic — you might say the needle of the gabfest, to employ a metaphor immediately understandable to people familiar with vinyl records, is stuck.

It’s stuck on Donald Trump.

Vice President Kamala Harris may have gone to high school here but Trump’s name is on every lip. The lingua franca of Canada may be hockey, but he’s the inevitable subject of every conversation. That, along with the violent, bloody civil war he will prompt if sent back to the White House. The tariffs he will impose. The jailings he will order. The international chaos he will set in motion. The destruction he will wreak.

And, only somewhat hyperbolically: The end of life as it is known in this (mostly peaceable) kingdom.

There is every indication that, with impatience with Justin Trudeau growing even among his onetime fervent supporters — his Liberal Party suffered an embarrassing special parliamentary election defeat in a onetime stronghold in Montreal earlier this month — Canada needs an election. The next scheduled national election is October 20, 2025, and Trudeau’s is a minority government, vulnerable to parliamentary non-confidence motions that could unleash a snap election.

But Canada is deeply involved in an election anyway. Ours.

The implications of a Trump presidency may have more serious immediate implications for Ukraine and Poland, but they cannot be underestimated for Canada, which along with Mexico is America’s closest neighbor, and is the nation’s biggest single trade partner — at nearly $1 trillion.

All of this angst, of course, is about Trump, the once and perhaps future most-important-person-on-earth. But some of it is about Canada. And it is deeply revealing about the country that sits to the north but which is far from the consciousness of most Americans, whose ignorance about their neighbor has long rankled Canadians. They cannot afford to be ignorant about the giant that lies below their southern border.

“It’s difficult for Canada not to be shocked by Trump’s language and style,” said Jennifer Welsh, who is the new director of McGill University’s Max Bell School of Public Policy, where I am beginning my sixth fall semester teaching about the United States. “That hasn’t been our language or our style. Americans have been living with this shift but here we still cannot comprehend a political leader talking the way Trump talks. It is still shocking to us.”

All of this angst, of course, is about Trump, the once and perhaps future most-important-person-on-earth. But some of it is about Canada.

But it is broader than that. A Pollara Strategic Insights poll taken this spring with Boston’s Emerson College found that only 3 percent of Canadians are “very satisfied” with the state of American democracy, a dissatisfaction that is spread among all 10 provinces and every age group. An important finding: About half (48 percent) believe that the political climate in the United States has an influence on the political climate here.

One of them is Vincent Rigby. “This is about Canada’s national interest,” the former Canadian national security adviser told me. “A very strong relationship with the United States is in our national interest, but if there’s trouble south of the border, there are repercussions for us. Political turmoil in the United States is not in our interest and we have to be ready to react — and adjust.”

Rigby is one of the authors of the landmark May 2022 study, “A National Security Strategy for the 2020s,” which spoke of the need for Canada to recognize that it “can no longer count on some of the traditional pillars that have guaranteed our security and prosperity for decades.” The task force that produced the report was organized by the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa, and the report warned that a “polarized United States has become a less predictable partner in recent years.”

The authors, mostly scholars and diplomats, argued that this is a particular peril because, as they put it, “Since the start of European settlement, Canadians have relied on others — first France, then Britain, now the United States — for protection.” The threat is that the anchor of Canada’s protection could now become a threat itself.

This theme has been prominent in Canada since Trump became a presidential candidate nine years ago.

Indeed, the titles of two of the most important books in Canada in recent years indicate the concern here. One is Stephen Marche’s The Next Civil War War: Dispatches from the American Future (2022). The other is Rob Goodman’s Not Here: Why American Democracy is Eroding and How Canada Can Protect Itself (2023).

I’ve read them both. I don’t recognize the country these books are talking about — but I recognize the worry they convey.

In Not Here, Goodman, who began teaching at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson University) after a career as a speechwriter on Capitol Hill, writes, “If America’s democratic erosion continues, it is hard to imagine Canada’s democracy remaining unscathed as long as it remains in a position of economic dependency on America.”

Stephen Marche, a prominent Canadian commentator, begins The Next Civil War with a chilling sentence: “The United States is coming to an end. The question is how.” He then goes on to say, “The United States is descending into the kind of sectarian conflict usually found in poor countries with histories of violence, not the world’s most enduring democracy and largest economy.

These two volumes come on the heels of a July 2022 article in The Walrus magazine titled “How an Unstable US Threatens Canada’s National Security,” in which Ira Wells, a University of Toronto professor of literature and cultural criticism, argued that, “for all of its continued economic dominance, the US often appears on the brink of anarchy.” Wells said that political violence south of the border might “involve complicated and unpredictable spillover events in Canada.”

Jeremy Kinsman, who served as a Canadian diplomat in Washington before being the country’s ambassador to Moscow, the United Kingdom (high commissioner in Canadian diplomatic parlance), and the European Union, speaks of “the carnival down South” and told me that Canadians are “in a state of bewilderment that so many Americans can, after January 6 and everything else, tolerate Donald Trump.” He called the phenomenon “a new glimpse into the state of humanity,” and he said “we are baffled by it.” And, like all his countrymen and women, it’s a subject he continually returns to as Canada, in the words of its national anthem, stands on guard.

David Shribman, a former Boston Globe Washington bureau chief and executive editor emeritus of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, is a dual citizen of Canada and the United States.