Mr. Biden Comes to Canada

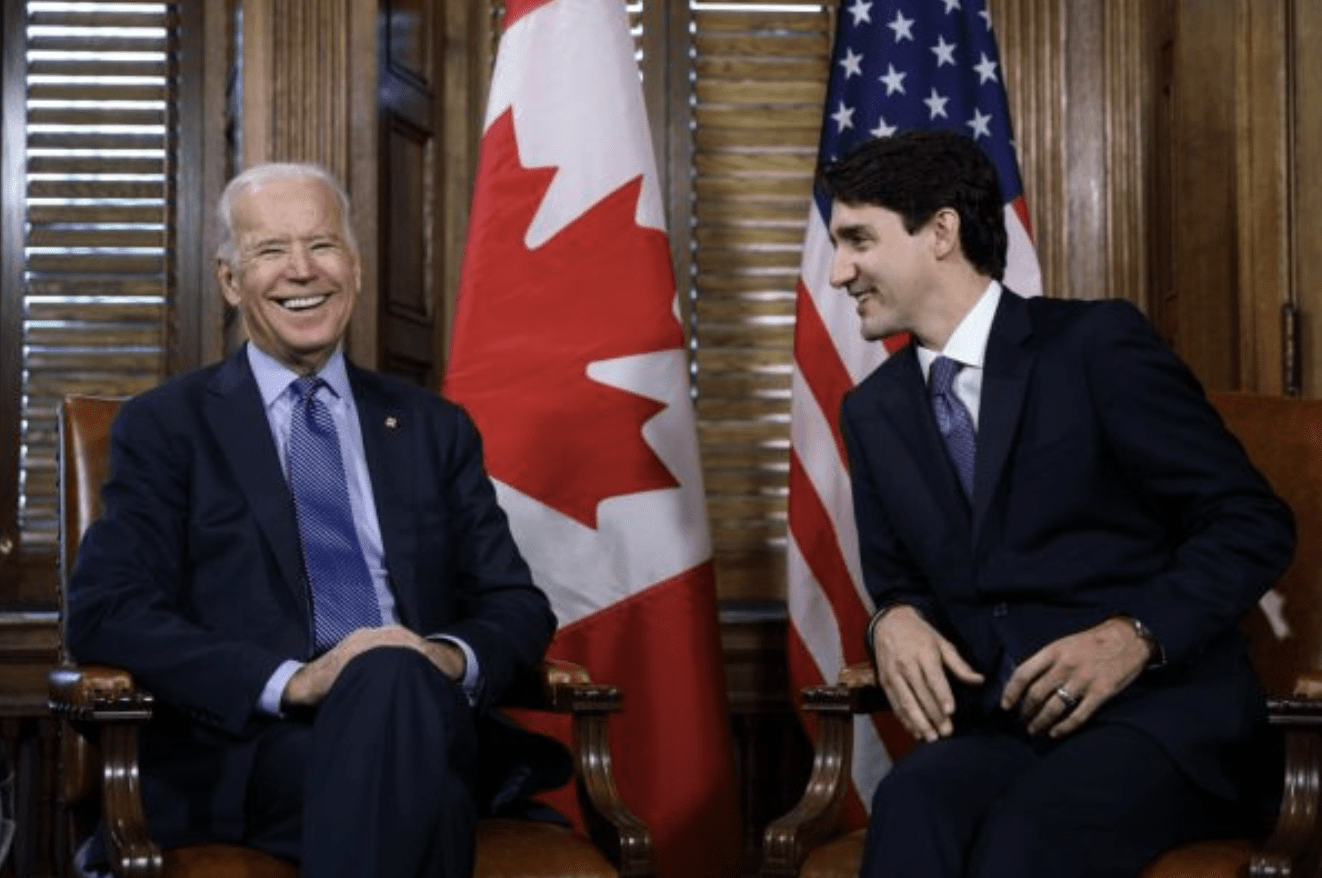

An easy rapport: The 2016 vice presidential Biden-Trudeau bilateral/Adam Scotti

An easy rapport: The 2016 vice presidential Biden-Trudeau bilateral/Adam Scotti

Colin Robertson

March 19, 2023

Meetings with American presidents on Canadian turf present rare opportunities for Canadian prime ministers. The overnight visit this Thursday and Friday, March 23-24 — especially the face-to-face time that Justin Trudeau will have with Joe Biden — must be used as effectively as possible.

Success means differentiating between the transactional and the important.

Discussion topics for the one-on-one time that the prime minister gets with the president require strategic culling. We can reasonably expect to get his personal attention for one, perhaps two key items, keeping in mind we do best when advancing a Canadian interest that also serves those of the US.

When we talk about resilience and reshoring our strategic supply chains, critical minerals have got to be top of the list. Trudeau should press for a joint approach in financing and regulatory approvals of the mining and refining of critical minerals necessary for our emerging EV auto industry and defence industry needs. Most of what we now produce is refined in China.

The second rule in these bilaterals is for Canadian PMs to offer constructive solutions on international issues; the daily preoccupation of US presidents.

As they compare notes on the recent visits to both Ottawa and Washington of key allies German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, Trudeau could propose that we jointly help ensure vital energy supply for our allies. Recognizing that the Administration just approved drilling for oil in Alaska, and that fossil fuels will be essential in the transition to cleaner energy the leaders could mandate, in time for the G7 summit (May 19-21) in Hiroshima, a fresh look at how we mobilize our joint energy capacity to help the allies?

Joe Biden is coming off a fortnight of travel as part of his continuous effort to shore up the alliances of democracies. There was the surprise visit to Kyiv and then the meeting with NATO’s Eastern Europe leadership in Warsaw. Last week in San Diego, Biden solidified the AUKUS alignment with Britain’s Rishi Sunak and Australia’s Anthony Albanese. Not surprisingly, given his former roles as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and vice president, Biden has international affairs, especially Alliance defence and security, high on his agenda. And, of course, Biden is expected to be announcing a 2024 re-election run sometime soon.

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has reset thinking in both the West and global south. For over seventy years we have relied on an international architecture — the United Nations, the Bretton Woods institutions and NATO — that kept us secure and made globalization possible. The US provided the security backstop: its Navy patrolling international sea-lanes and its nuclear arms providing the ultimate deterrent.

The Russian invasion brings a new clarity to international relations by way of defining the motives and intentions of major actors that were previously obscured by incrementalism and camouflaged by proxyism. We are at a point that, if we are to avoid conflict, will require extraordinary diplomacy and statecraft backed by hard power.

The British have just refreshed their defence review. Australia is buying nuclear submarines through AUKUS. The Japanese are re-arming in ways not seen since the Second World War. America’s most important treaty allies are all rethinking their situations because of the threats posed by Beijing and Moscow. Successive American administrations have strived to get the allies to do more. Now they must.

At 1.27 precent of GDP, Canada sits in the bottom quartile for defence spending within the 30-member NATO alliance. We are nowhere near achieving the Alliance’s pledge of 2 percent of GDP by 2024, reaffirmed again last June by leaders at their Madrid Summit.

Barack Obama was the last American president to make an official visit to Canada in June 2016 and he repeatedly told Canada’s parliamentarians that “NATO needs more Canada”. We can expect Biden to be equally forceful and to ask us to do more in the Arctic.

We should do more. Canada’s North lacks its promised ports and icebreakers and our Arctic offshore patrol ships are only now coming into service. We hope that our new icebreakers will be at sea in the early 2030s. Our next generation of submarines, which we hope will have greater capacity to operate under-ice, have yet to be designed, let alone turned over to a defence procurement process aptly described by some experts as a “wicked problem” for Canadians”.

The Russian invasion brings a new clarity to international relations by way of defining the motives and intentions of major actors that were previously obscured by incrementalism and camouflaged by proxyism.

In recent months, the government has announced the purchase of 88 F-35s and refueling aircraft, with more money for continental defence and NORAD modernization. Both decisions are long overdue. We await the defence review update, originally promised for September, that is also supposed to address missile defence.

These are all items of concern to the Biden that we should make part of NORAD renewal. The cost sharing formula for NORAD modernization is US 60/Canada 40 and we should act now. Or would we rather risk dealing with a second Trump or Trump-like administration?

The March 28 budget is expected to prioritize affordability, developing the clean economy and health care. The “iron ladies” – Chrystia Freeland, Mélanie Joly, and Anita Anand – would like more for defence; they are a minority within cabinet. At lunch in the 1990s with Geoffrey Pearson, my first big boss at External Affairs whose service included a posting as ambassador to Moscow, Pearson said that we’d forgotten that while his father, Lester Pearson, had championed peacekeeping and ‘soft power’, the Pearsonian formula was based on soft power backed up by hard power. Successive governments, Liberal and Conservative, forgot this.

In announcing Biden’s visit, the White House put Haiti on the agenda because they’d like us to lead the effort to restore what is rapidly emerging as the latest failed state in a growing list from Afghanistan to Yemen. But rebuilding requires stability in Haiti. As Chief of the Defence Staff Wayne Eyre said earlier this month, Canada’s Armed Forces — already spread thin with Ukraine and NATO — likely lack the capability and capacity to take it on.

Canadian business wants access to the massive US investments funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. In his February State of the Union address President Biden was clear that investments must boost “American-made goods”. As a free trade partner, we get some privileged access. So, too, with our longstanding defence procurement agreements.

As we have learned, Canadian business must wage a permanent campaign to convince American legislators to “Buy North American”. We improve our chances when Canadian labour is part of that effort and we are able to gain the support of American business and labor unions.

Our border management system has not kept pace with available technology. The US is applying digital border security processes. Having just passed through Charlotte, North Carolina where all I had to do was look in a camera and then get a card that allowed a fast-pass to catch my next flight, I can attest that it is a lot smoother than passing through Canadian entry at Pearson. There is much we can learn from the practical work of the Future Borders Coalition.

The re-negotiation of the Columbia River Treaty that began in 2018 needs a push. The Treaty manages flood control, providing hydro power for seven states and British Columbia. After 15 rounds of negotiations, the leaders need to make it happen. In September 2024, its termination provisions kick-in. Again, do we want to wait and risk negotiations with a Trump-like administration?

The Arctic Council, which has not met since the Russian invasion, will resume when Norway takes the chair in May. With Russia suspended, the other members, including Canada, the United States, Iceland, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Sweden, are all or will soon be NATO members. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg recently visited the Canadian North with Trudeau to underline “the High North’s strategic importance for Euro-Atlantic security.” Now, we need to flesh this out.

Using bilateral face-time strategically means delegating the transactional to the responsible ministers and secretaries, working in tandem with our respective ambassadors, Kirsten Hillman in Washington and David Cohen in Ottawa.

The brief window before the visit, when the US National Security Council and its inter-agency overview looks at the relationship, is the time to make progress on these irritants. We need to avoid putting them on the top-table agenda. Then National Security Advisor Condi Rice was exasperated by the Canadians’ tendency to lead with ‘condominium issues’. The president’s eyes would quickly glaze over. The ‘small-ball’ discussion reminded his team of meetings with state governors. But the overlap between domestic and international is also a reflection of the deep integration of the Canada-US relationship.

Using bilateral face-time strategically means delegating the transactional to the responsible ministers and secretaries, working in tandem with our respective ambassadors, Kirsten Hillman in Washington and David Cohen in Ottawa.

The current transactional list includes the perennial trade irritants — notably “Buy American” as well as border management and fixing the loophole in the Safe ThirdCountry Agreement responsible for the Roxham Road entry-point for asylum seekers. The CUSMA dispute settlement mechanism is working with positive effect in curbing Canadian protectionism on dairy and US protectionism on rules of origin.

After two years, the cabinet relationships are working well, with Canadian ministers getting their calls returned. Leave it to them to do the stock-taking that will be based on the 2021 Roadmap for a Renewed Canada-US Partnership agreed in the February 2021 bilateral.

The Roadmap lays out a joint-action blueprint on COVID (and preparing for next time), climate (where we are mostly in sync), building back better (where we should be in sync but aren’t, especially in border management), diversity and inclusion (totally in sync), security and defence (where Canada gets a failing grade) and bolstering global alliances (where Canadian commitment does not match its rhetoric).

When effectively managed, presidential visits to Canada can advance Canadian interests.

Thirty-six years ago, at another Ottawa summit, Brian Mulroney persuaded Ronald Reagan to acknowledge Canada’s claim to the Northwest Passage. The quid pro quo from the American perspective was that if Canada claimed sovereignty, then it must exercise that sovereignty to preclude third parties from filling the vacuum.

Mulroney also persuaded a skeptical Reagan to invest in acid rain mitigation projects and within five years Mulroney and George H.W. Bush signed the Acid Rain Accord. The conversation that Bill Clinton had with Jean Chrétien during the president’s Ottawa visit in October 1999 led Clinton to jettison his prepared remarks and give at Mont Tremblant what is still the best enunciation of federalism.

This is Joe Biden’s 11th international trip and the 18th country he has visited. For those suggesting this reflects a lack of attention to Canada, we need to remember that the Biden-Trudeau relationship is solid. The first bilateral of Biden’s presidency was a virtual meeting with Trudeau in February 2021, when COVID restrictions prevented travel. For those who still feel “the Americans” pay us insufficient attention, Allan Gotlieb, our longest-serving Canadian ambassador to the US, always cautioned to consider the alternative, given that Washington’s instinctive problem-solving reflex is to reach for a hammer.

Ultimately, the American relationship is the one that Canada really has to get right.

The Trudeau government has done a credible job in cultivating Congress. Ministers regularly include calls to Capitol Hill while in Washington. But, certainly in normal administrations, the White House remains our best access point into the American system. Prime ministers need to proceed carefully and without illusion.

Trudeau has managed well his personal relationships with three presidents: the ‘bromance’ with Obama, the strategic humouring of Trump and his obvious comfort level, personally and politically, with the avuncular Biden. During Biden’s last visit to Ottawa as outgoing vice president in December 2016, he passed to Trudeau the torch of leading the “liberal international order”. Trudeau has certainly championed inclusion and diversity, gender equality, and climate. But not defence.

We share with the US values but our interests and priorities sometimes differ. The Canadian challenge is to manage these differences and to offer initiatives that solve problems and advance the Canadian interest. But in a world getting smaller and meaner, we must also pull our share of collective security. It’s what makes possible that which we value.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat who served extensively in the United States, is a Fellow and Senior Adviser with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.