Moving Ahead After Ten Years of Trade Tumult

Between the systemic lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic and those related to the world’s geopolitical ructions of the past 20 years, many of the disruptions, obstructions and frictions in the global trade regime of the past decade have clarified recently. While Canada has taken a lead in World Trade Organization reform, longtime diplomat Colin Robertson has some further advice on how to move forward.

Colin Robertson

Canada’s global trade and productivity is heading in the wrong direction and with the return of great power competition and protectionism, we need to adapt and adjust.

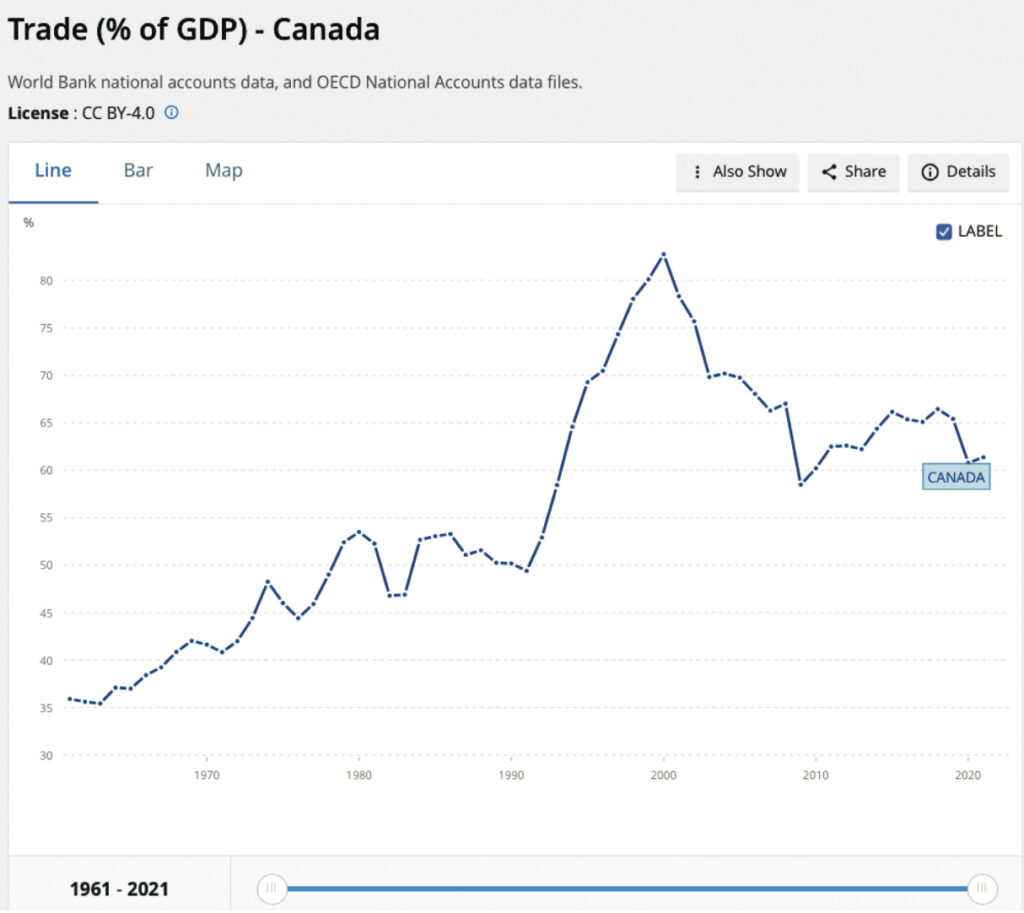

The World Bank numbers tell the trade story. In 1987, the year the original Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (FTA) was negotiated, Canada’s trade-to-GDP was 51 percent. By 1994, as North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was implemented, it had risen to 64 percent and in 2000, it peaked at 83 percent. By 2021, it had declined to 61 percent, down from 66 percent in the pre-pandemic year of 2018.

The fault is not with our trade negotiators. Since the mid-1980s, Canadian governments complemented the ongoing multilateral negotiations within the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) process — the precursor to the World Trade Organization (WTO) — with a series of high-standard trade deals beginning with the Canada-US FTA (1987-88), NAFTA (1993-94), the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with Europe (CETA) in 2016, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in 2018 and then the renegotiated NAFTA, known in Canada as the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) in 2020. Uniquely among our G7 partners, our 15 free trade agreements (FTAs) now cover 61 percent of the world’s GDP, comprising 1.5 billion consumers in 51 countries.

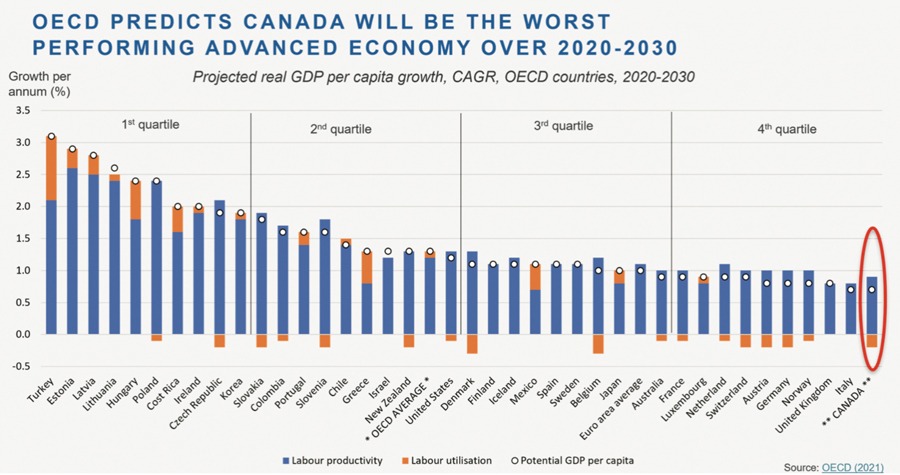

As Canadian trade performance has slipped, so has our productivity. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data reveals that from 2007-2020, Canada’s real GDP per capita grew annually by 0.8 percent, placing us in the third quartile among advanced nations. While longer-term economic forecasting is always dodgy, their forward projection for the next decade put Canada in the bottom quartile. It may be wrong, but we need to take heed.

Productivity matters because it is the measurement of a nation’s production of goods and services based on the amount of inputs — labour, capital, energy, or other resources — used in creating goods and services.

Global geopolitics is also changing and forcing us to rethink how we do trade policy. For decades, it was all about trade liberalization based on agreed rules and shared norms designed to promote openness. Now, it is about setting standards for transparency, labour and environment, and new sectors like e-commerce as well as border adjustment levies based on carbon content and climate commitments.

With more countries pursuing protectionism at home, the trade zeitgeist is now veering towards zero-sum competition. The degradation of the post-GATT status quo began with with China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. Despite hopes that China would become a “responsible stakeholder”, China never bought into the rules-based order, continued its subsidies and state control, and used its membership in the WTO to obstruct and bend the organization toward its own needs and norms.

Now the US and the European Union are re-embracing industrial policy with subsidies and tax credits. This is setting off a global race to attract new industry, especially in manufacturing. The US also says subsidizing clean energy is good for the climate and that they can both re-industrialize and de-carbonize at the same time. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen put it: “We view this period as a time when we renewed America’s economic strength. We are positioning America to build, innovate, and lead in the 21st century.”

The allies, especially in the EU as French President Emmanuel Macron forcefully made clear when in Washington, see it as an American grab for the jobs that will be created by the new “green” economy. President Biden has promised “tweaks” to assuage their concerns.

In geostrategic terms, it would make more sense for the US to lead the allies who share the same values, to harmonize industrial policy with agreed disciplines on subsidies. For those who fail to meet their climate commitments, there will be border adjustment levies.

Meanwhile, the rules-based trading system that generations of Canadians worked hard to build and sustain isn’t working as intended. The WTO can no longer negotiate global trade agreements and its vital dispute settlement capacity is paralyzed and while Canada is leading efforts to fix it, we aren’t there yet. We still depend on previously negotiated disciplines on, for example, anti-dumping, export subsidies for agriculture, and its information technology agreement. WTO research is indispensable and, like the United Nations General Assembly, it remains a key link in the multilateral chain.

But like the UN, the WTO needs reform. There is a growing recognition that global institutions are hamstrung by large autocracies that don’t just flout the rules but attempt to rewrite them from within, often by proxy.

So, how can Canada adjust, adapt and take advantage of our key inputs including our natural resources, our educated work force and our policy predictability — through transitions in Conservative and Liberal governments — on liberalized trade?

Here are ten ideas to stimulate discussion and policy action:

1. We need an industrial strategy that puts the emphasis on productivity investments. A compelling case for both is contained in reports by Canada’s Industry Strategy Council (2020) and the Senate Prosperity Action Group (2021).

Specifically, this means becoming a digital and data-driven economy; becoming the ESG world leader in resources, clean energy, and clean technology; building innovative and high-value manufacturing in areas such as EV batteries, where we can lead globally because of our natural resources, coupled with a skilled and innovative workforce; and leverage our agri-food advantage to feed the planet.

In practical terms, it means building out the work begun with the National Policy Framework for Strategic Gateways and Trade (2007) and taking a long-term perspective by developing a rolling, 50-year trade corridors and gateways national infrastructure plan. We can learn lessons from the kind of P3 exercise that is building the Gordie Howe Bridge.

Long-term funding should rely not just on taxpayers but on our largest pension funds — the “Maple 8” — whose managers will ensure value for money.

A caution: Industrial policy enjoyed its hey-day in the 1950s and 1960s but then fell out of fashion because it generated higher prices for consumers, excess public spending, investments untethered from market realities, and trade disputes with allies. As the great 20th-century mandarin and diplomat, Sylvia Ostry, once told us: “Government is really bad at picking winners but losers are very good at picking the pockets of taxpayers.”

2. We need to bust our internal trade barriers: Premiers can fix this by liberalizing trade, the unfinished business of Confederation. Study after study demonstrate that these continuing barriers rob governments, business and consumers.

As the IMF Canada report (2019) concluded: “Barriers to domestic trade is a longstanding issue and nothing short of a sustained and concerted collective effort is needed to break down barriers that are impeding Canadian businesses from competing on a level playing field and scaling-up.” A recent Macdonald-Laurier Institute study (2022) argues for adopting mutual recognition whereby the regulatory requirements met for one provincial or territorial government automatically satisfy the requirements for another.

In unilaterally dropping barriers, former Alberta premier Jason Kenney set the bar and diagnosed the problem: “Behind every barrier to trade, competitive procurement, or labour mobility there is some interest group seeking protection. There are no strong political incentives to trump that resistance, and internal trade will never be a retail political issue.”

3. We need a “C.D. Howe moment”. It starts with the appointment of a minister with the authorities of a Howe, who can work closely with industry and labour across the areas of energy, agri-food and defence with the goal of cutting through red tape and executing a plan to build our digital and physical infrastructure while fueling and feeding our allies.

4. Make what the market will buy rather than what we want to sell. According to Global Affairs assessments, our trade utilization rate— the share of trade entering under the negotiated preferential rates — is poor. For CETA it is 57 percent while for CUSMA it is 69 percent. While posted in Hong Kong, I marveled at the success of the Hong Kong Trade Development Council. Their secret: their agents abroad focused on what the market wanted and then their headquarters identified companies that could make the product. It required close knowledge of capacity combined with practical skills development. Our Trade Commissioner Service can learn from their experience.

5. Market Canada as a premium brand. Canada ranks third in the index of countries with the best quality of life. In the Index of Economic Freedom, Canada is ranked 1st among 32 countries in the Americas region. Our cities are the most livable in North America. Our marketing should pitch Canadian goods and services as a premium brand. Our resources — mined, grown and harvested from land and sea— are developed responsibly and sustainably and help to feed and fuel the world. Our manufacturing is innovative and of top quality and our banking and insurance institutions are secure and reliable — a distinction made clear to the world after the 2008 financial crash. Our education system ranks in the top five of nations and we rank in the top ten of innovative nations. Our cultural diversity is one of our greatest assets and we continue to welcome newcomers, with half of those living in our largest city, Toronto, born outside of Canada.

Like the UN, the WTO needs reform. There is a growing recognition that global institutions are hamstrung by large autocracies that don’t just flout the rules but attempt to rewrite them from within, often by proxy.

6. Link trade and talent: Look anywhere in the world and Canada is consistently in the top tier of those places people want to visit, study or live. But Canada’s fertility rate — 1.4 children per woman — falls below replacement so we need to link more closely our trade, investment and labour objectives with our immigration strategy. Our tourism promotion should also pitch Canada not just as a place to visit but as a place to study, work and live.

7. Use our diaspora: As John Stackhouse recounts in his Planet Canada: How Our Expats Are Shaping the Future we have talent abroad that we should harness. I learned this while serving as our Consul General in California. The young Canadian engineers we enlisted into the Digital Moose Lounge in Silicon Valley were my best entrée to the hi-tech companies whose investment we sought. Many of them have since become key members in the C-100 of Canadian venture capitalists in Silicon Valley. It was a similar story in Los Angeles where the doors to film and video production in Canada were opened by the talent working in Hollywood. In Singapore and Hong Kong our alumni associations are often more active than those in Canada and, again, they open doors.

8. Set objectives and scorecard results: As a standing item at meetings of the prime minister and premiers, they should agree to annual trade and investment objectives then scorecard the results. Trade ministers can then do the follow-up at their regular meetings. The scorecard needs to be widely distributed and easily available so Canadians can see successes and shortcomings

9. Coordinate policy development with our research institutes: We need more intelligence and research capacity on trade. Expanding and diversifying trade and inbound investment should be the overriding goal of our trade development plans, country-by-country and, in the case of the US, state-by-state. Data show that Canada’s exports are the fourth most concentrated by destination out of 113 countries, principally due to the large share of exports going to the United States. It is the biggest consumer market in the world, as we have learned on resources like oil and gas. But, when you have only one buyer, they set the price. Given Canadian dependence on trade, we would benefit from a coordinated approach to policy prescriptive research and analysis aimed at diversifying our markets.

10. Educate Canadians on Why Trade Matters: We need an ongoing public information campaign to inform and educate Canadians of the value of trade to our economy. Few have any idea that trade — internal and external — generates two-thirds of our national income. Economists estimate that incomes in Canada are 15 to 40 percent higher thanks to freer trade. Canada is home to over 50,000 exporters and 120,000 importers. Provincial governments should mandate teaching the importance of trade to the local community and their province as a part of the curriculum in schools.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a Fellow and Senior Adviser with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.