Modern Monetary Maestros

Douglas Porter

December 1, 2023

Former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan was sometimes called the Maestro, for his ability to successfully guide policy through the shoals—well, until his reputation was sullied by that messy business of the Global Financial Crisis erupting shortly after his reign. That episode showed that care and time are required before handing out the lifetime monetary policy trophies. But it may not be premature in the current cycle to at least start bringing out the Maestro participation awards for the current crop of central bankers. That’s because they have so far managed to see inflation down by 5-to-6 percentage points (or even more) from last year’s peaks, without unleashing a full-on recession. That is one impressive feat, an accomplishment that financial markets are gradually beginning to more fully appreciate.

With a wide variety of economies reporting better-than-expected headline and core inflation trends in recent weeks, the fever has clearly and decisively broken for bond yields. In turn, this has forcefully fired up equities, supporting a banner month for global financial markets. Courtesy of a roughly 75 bp drop in long-term bond yields from the October peak, the S&P 500 surged 8.9% last month, while even the TSX advanced 7.2% (its fourth-best month since 2009). Instead of wondering whether the central banks were done hiking, markets are now focused on when the rate cuts may commence, and how fast they will come down. Essentially, in a mere matter of weeks, the narrative has gone from ‘higher for longer-er’ to ‘rate cuts are imminent’.

Fed Governor Waller threw a large log on the fire this week by openly mouthing that rate cuts could happen if inflation continues to come down nicely for a number of months. Given that Waller has been of the hawkish persuasion previously, these remarks truly caught the market’s fancy, even if the words weren’t especially shocking. Other Fed officials attempted to douse the flames a bit, gamely suggesting that rate hikes are still possible should inflation disappoint, but investors mostly tuned out such talk. Even Powell’s “cool it on the rate cut speculation” message in Friday remarks held little sway. The Chair cannot be amused by the exuberance seeping back into the market, with an early warning signal from Bitcoin taking aim at $40k and the meme stocks (e.g., Gamestop) turning notably higher—likely not part of the Fed’s plan to restore price stability, and quash inflation expectations.

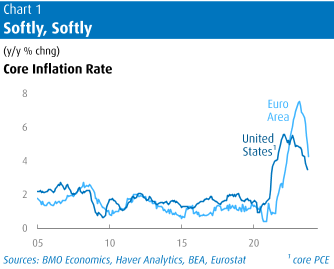

Europe got into the act this week, with a much milder-than-anticipated first reading on November inflation. Kicked off by a big drop in Germany’s CPI, which sliced the yearly inflation rate to 2.3%, the Euro Area also chopped its headline rate by half a point to 2.4%. A few semi-major European economies have already broken below the 2% threshold, with the Netherlands at 1.3%, Italy at 0.7%, and Belgium posting a 0.7% drop in consumer prices over the past year. True, these results benefit heavily from base effects—Europe’s inflation peaked last fall at above10%—but the turnabout has been dramatic. But, no, Team Transitory cannot declare victory; inflation has still averaged nearly 6% in the three years since prices began rumbling higher, or almost four times the pre-pandemic pace. And, core inflation in the Euro Area is still a meaty 4.2% y/y (Chart 1). Better, but not good.

The major U.S. inflation reading this week landed squarely on consensus, with the core PCE deflator rising a mild 0.2% in October, shaving the annual increase to a tolerable 3.5%. That’s the coolest pace in two and a half years, and well below last year’s peak of 5.6% (which was hit just before the Fed began tightening). Shorter-term metrics have eased to just below 2.5%, pointing to further moderation in coming months. In fact, this key gauge could easily be printing two-handles on the yearly measure by early 2024 if recent mild monthly trends persist. That, along with a cooler economy, helps explain why the market is already building in better-than-even odds of a rate cut by March.

It may seem a bit passing strange to be talking about a cooler economy, when U.S. Q3 GDP was just revised up to a towering 5.2% clip. But evidence continues to build that growth has slowed markedly in Q4. The factory ISM stayed chilly at 46.7 in November, while housing is in a funk (see this week’s Focus Feature), and the trade deficit seems to be widening again. Of course we need to wait until the big dog has weighed in—next Friday’s payroll report is expected to reveal a moderate 170,000 jobs gain, and a 3.9% unemployment rate. Even a slight upside surprise in the latter would meet the Sahm Rule (i.e., flagging recession risk), since it would bring the three-month average jobless rate to 3.9%, a full 0.5 ppts above the early-year low of 3.4%. Again, it’s tough to square recession talk with the recent torrid GDP growth and solid job gains.

A recession conversation has been much more realistic in Canada, where the economy has struggled to grow at all since early this year. But even as Q3 GDP surprisingly fell at a 1.1% annual rate, the prior quarter was revised up to a 1.4% gain (from an initial -0.2%), avoiding two consecutive quarters of decline. And, perhaps the biggest surprise in this week’s batch of GDP results was an initial estimate of a 0.2% rise for October, setting Q4 off on a decent footing. We have thus nudged up our Q4 forecast to flat (previously had -1.0% a.r.). Still, the bigger picture is that the full-year growth rate will be a skimpy 1.0% in 2023, and just 0.5% in 2024 (both are unchanged from our previous estimates, as the many GDP cross currents came out in the wash).

November’s employment report was consistent with the theme of a Canadian economy treading water and just keeping its head above the recession line. Indeed, job gains slightly topped consensus at 25,000, with respectable details. However, as we have noted many times before, raging population growth means that the economy requires nearly 50,000 net new jobs a month to keep the jobless rate from rising. Yet, rising it is; the unemployment rate nudged up to 5.8% in November, up 0.8 ppts from the 5.0% ebb early this year, and it seems to be on a steady one-way trip north. Concurrently, the job vacancy rate has eased to 3.6%, nearly back to pre-pandemic levels and down more than 2 ppts from 2022 highs. Suffice it to say that the job market is no longer drum tight… it may be fair to ask if it can even still be considered tight.

Meantime, Canada’s inflation performance has also improved remarkably in recent months. Removing those pesky mortgage interest costs reveals that CPI has risen a modest 2.2% in the past year, albeit most measures of core are still running at roughly a 3% clip in the past six months. The combination of a stall in growth, a steadily rising jobless rate, and fading inflation have domestic markets looking ahead to rate cuts, with many already circling March as a possibility.

Wednesday’s BoC rate decision is the big event on next week’s Canada calendar, and is a grand opportunity for the Bank to fine-tune the message. We suspect that much like Powell, the Bank will continue to sing from the hawkish song sheet, still openly talking about the possibility of rate hikes, not cuts. As we have often opined, the central banks are likely to err on the side of staying too tight for too long, rather than easing up on the inflation fight too soon. After all, a renewed rising crescendo of inflation would sound a sour note indeed for the 2024 outlook.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.