Minority Mood Music

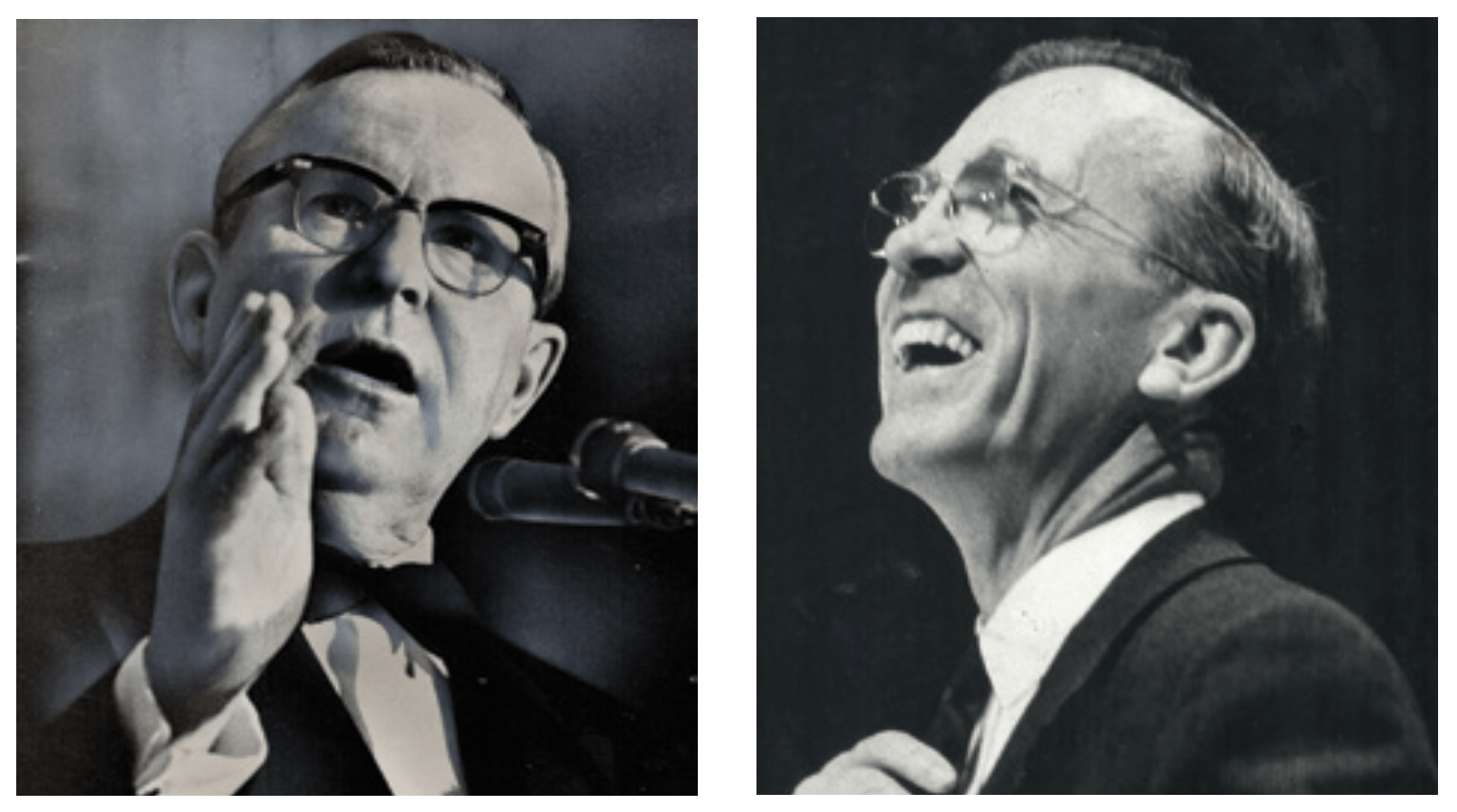

Canada has a notable history of minority governments, some of them the most productive and successful of their times. The Liberal minorities of 1963-68, supported by the NDP, left an enviable record of achievement. This was due to the leadership of Lester Pearson as prime minister, and the vision of Tommy Douglas holding the balance of power. Their record includes Medicare, the Canada-Quebec Pension Plan and, not least, the Maple Leaf flag. As Robin Sears writes, Pearson and Douglas set the standard for success.

Robin V. Sears

Successful minority governments are more a matter of nuance than numbers, more about mood and motivation than method. Canadians, not surprisingly, are quite good at managing minority governments both federal and provincial. We’ve had many and most had impressive records of achievement.

Two seasoned House leaders, given a broad mandate, can facilitate the smooth passage of even challenging legislation in a minority Parliament, often better than a majority government House leader with a hammer.

In the irrational digital sturm und drang that passes for political gamesmanship today, what is often lost is the reality that the geniuses of parliamentary mastery always understood that there needs to be something for both sides, or even all sides. The “I win, so you must lose” zero-sum game of the Harper era can work, but not for long, and not without high cost. The losers—often including government backbenchers—eventually unite in “working to rule” or even open revolt.

Marshalling the votes for a tough legislative victory in the United States Senate is similar to our minority House management, but harder because you have dozens of interests to balance and placate. As Robert Caro describes it in his magisterial biographies of Lyndon B. Johnson, the Democratic majority leader in the Senate persuaded, cajoled, threatened and pleaded for months to get the Senate votes required to pass Republican President Dwight Eisenhower’s civil rights legislation in the 1950s, and his own landmark civil rights bills as president in the 1960s.

The final 100 pages of his Master of the Senate are devoted to a day-by-day chronicle of that epochal achievement. As Caro says, “…there are cases in which the differences between the two sides are so deep that no meeting placed can be located, for no such place exists…[then] it is necessary for the legislative leader to create a common ground.” This is what LBJ achieved several times, notably working with President Eisenhower during the Little Rock crisis of 1957, when the governor of Arkansas barred African Americans from a local school, in violation of the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education against segregation of public schools. Johnson’s own civil rights bill of 1965, passed by his former Senate colleagues, completed the historic work begun by President John F. Kennedy.

When Lester Pearson and Tommy Douglas worked together in those same years in two minority governments from 1963-68, we had a seasoned international Nobel Prize winning diplomat in one chair, and the premier who had dragged Saskatchewan from bankruptcy to stability through years of painful compromises on programs, taxes and creditor battles, in the other. They were leaders who well understood that the winner cannot take all.

The parallels with today are fascinating. It was the time of nationalist sentiment rising in Quebec, strong pressure from Conservative premiers for a larger share of the fiscal pie, and deep concerns about national unity.

A strong cabinet, capable advisers to the prime minister in Tom Kent, Richard O’Hagan and Jim Coutts, along with shared political agenda items with the New Democrats made for formidable and lasting achievements. Among them were the Canadian Maple Leaf flag, universal health care, the Canada-Quebec Pension Plan and the beginning of new fiscal arrangements with the provinces.

The next minority period, 1972-74, was shorter and more intense in every respect, but equally full of legislative landmarks, including consumer price controls, limits on election expenses, and more generous pensions. As he had been in the earlier period, NDP House Leader Stanley Knowles was an effective go-between.

NDP Leader David Lewis and Pierre Trudeau had a cooler relationship than did Douglas and Pearson, but it was respectful and effective. Only when it became difficult for each party to defend to their own activists why they were ‘’sleeping with the enemy’’ did the compromise process come to an abrupt end in the spring of 1974, when the Liberals famously arranged their own defeat over John Turner’s budget and were returned with a majority government. Interestingly, David Lewis’ son Stephen then stepped into a similar minority success, as Ontario NDP leader, with Ontario Conservative Premier Bill Davis for another two-year period from 1975 to 1977.

Neither the Martin nor the Harper minority eras in the early 2000s could be seen to have reached the same heights as those earlier periods, in terms of either co-operation or achievement. Politics had hardened and the activist cores of each of the parties were even more skeptical of the wisdom of co-operation.

Martin’s 2004 minority of a year and a few months was also hobbled by the continuing civil war in the Liberal Party, between his often over-confident and too- confrontational advisers and the Chrétien-ites still bitter at what they saw as their leader’s ouster. They misjudged NDP Leader Jack Layton and he organized their defeat in the House in late 2005, and hurt them on the hustings as well. The result was the 2006 Conservative minority replacing the Liberal one.

Harper’s approach was unique in Canadian politics, and will hopefully not be repeated in this minority or in any future governments seeking collaboration and partners in pushing through their legislative agenda.

It was a high-wire act that consisted mainly of threats and provocation directed mostly at the Liberals. The Liberals were deeply weakened by a succession of poor leadership choices, and the residue of the decade-long civil war between the Chrétien loyalists and the Martin insurgents. Tory partisans of the era maintained it worked well, as they forced the Liberals to vote with them more than 100 times over the period from 2006 to 2011, in two separate minority governments.

A more nuanced view, perhaps, is that it hardened the Harper approach to his majority government when he won it, and poisoned the view of many Canadians towards his style of politics. The content was less Draconian than advertised, but promoted with heated and aggressive partisan rhetoric, which deeply soured Canadian federal politics. The seeds of his heavy defeat in 2015 can be traced, in part, to the manner in which he managed power when he needed partners.

The tone-deaf arrogance that is often seen to be in the DNA of federal Liberals has led many commentators to suggest that Trudeau will be more of the Harper school than Pearsonian in his approach to minority management. That appears doubtful for two reasons. The first is that the Liberals have many more challengers to balance and appease than most federal governments, with hostile premiers in more than half of the provinces.

Those premiers will be tempted to push the federal Tories, and the Bloc, to be more difficult if they feel Ottawa needs pressure to bend on their grievances. Secondly, it seems likely that enough Liberals of an older generation remain who will point to the truncated success of Stephen Harper—and the continuing reputational damage the party still carries—as a result of his rougher, more American style of politics and governing.

For harder-edged Liberal advisers, the distraction of the leadership campaign within the Conservative Party will be tempting to make even more disabling through rough House tactics. The political success of Jagmeet Singh in leading the New Democrats in staving off a resounding defeat in the recent campaign is not matched by their financial health—bluntly stated, the New Dems are broke. For the same political pounders around Trudeau, humiliating New Democrats will be similarly tempting, as the enthusiasm to bring the government down will not become a real threat until this time next year at the earliest.

If Trudeau has matured sufficiently to understand that his best chance of regaining a majority is campaigning on some achievements, won by partnership and compromise in this Parliament, Canadians can look forward to another successful minority chapter probably lasting two to three years. If not, an election forced over their second budget in the spring of 2021 would be more likely, if our minority history is any guide.

Perhaps the stars will align for a return to a more mature minority government style again. And the math of a minority House such as this one, where the balance of power is shared, is impossible to predict.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears is a Sunday columnist with The Toronto Star and former national director of the NDP during the Broadbent years.