Memories of My Father: Sharing a Mission, 50 Years Apart

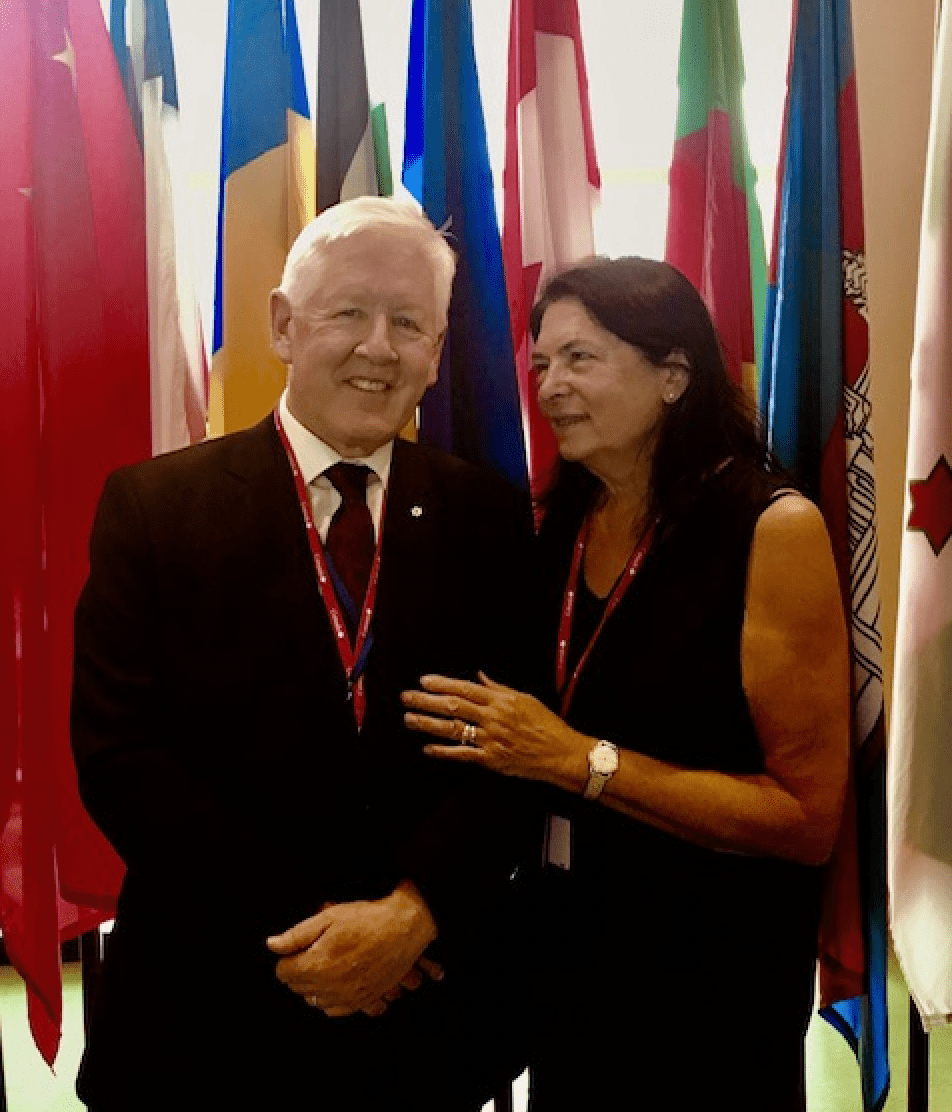

Newly sworn in at the UN with my wife, Arlene Perly Rae/Courtesy

Bob Rae

December 22, 2022

The day I was sworn in as Canadian Ambassador to the United Nations in August, 2020, I naturally thought of my Dad’s journey to the same job some 50 years before. To be able to share a quiet moment with my wife, Arlene, as we embarked on this journey was especially meaningful, as she had got to know my father well before his passing in 1999.

Much has changed since that time…but some things have not.

My father Saul joined the foreign service in the summer of 1940. With the help of a Massey Fellowship, he had gone from the University of Toronto to the London School of Economics, where he received a doctorate in 1938, followed by a postgraduate year at Oxford. After his LSE thesis — called “Public Opinion and its Measurement” — made its way to Dr. George Gallup (“Ted” to this friends), Saul was offered a job at the American Institute of Public Opinion in Princeton, New Jersey. He and my mother Lois, who was English, spent their first year of marriage there, then drove up to Ottawa in an old Ford. He soon went to work as executive assistant to Norman Robertson, who had been promoted to under-secretary (what we would now call a deputy minister) for External Affairs when the hard-driving Dr O.D. Skelton died of a massive heart attack.

The Department, as it immodestly called itself, was located in the East Block on Parliament Hill. It consisted of fewer than a hundred employees, with missions in London, Paris, Washington and Geneva, and its entire preoccupation in 1940 was the prosecution of the war effort. The prime minister of the day, Mackenzie King, had his offices in the same building, as did his small personal staff and the Privy Council. My Dad’s “class” at that time included Herbert Norman, Arthur Menzies, Ralph Collins, Ed Ritchie, and others who would go on to become pillars of Canadian diplomacy. The foreign service grew during the war with new recruits, and then more substantially in the years after 1945, when Canada was playing an ever-increasing role in creating the institutions that marked the post-war international order.

Work was endless, morale was high, and my father’s life was a strong combination of deep policy engagement and boundless mirth and humour. He had spent his early days on the vaudeville stage, with his sister Grace and his younger brother Jackie, in an act dubbed “The Three Little Raes of Sunshine”. His love of music and comedy never left him, held in check only by a fear that he might not be taken as seriously as some of his fellow diplomats.

After working at the centre of things in Ottawa for a couple of years, he was sent off to join General Georges P. Vanier in Algiers, leaving his pregnant wife behind. When France was liberated, he went to Paris to reclaim the Embassy. My mother and my sister Jennifer were reunited with him there and brother John arrived in October of 1945, baptized as John Alain Rae. Dad served as Secretary of the Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference.

Postings to Ottawa (I arrived in August of 1948), London, New York (as assistant to Lester Pearson when he served as president of the UN General Assembly), Hanoi — serving alone for more than a year with the Inter- national Control Commission — Washington (David arriving in 1957), Geneva, Mexico, the UN again, and finally at The Hague, from where he retired in 1980.

My Dad, Saul Rae, at the United Nations/UN photo

He was happiest serving abroad, as The Department grew bigger, eventually moving to the Pearson Building, a fortress on Sussex Drive. He felt that life in diplomacy was becoming too bureaucratic, too layered, too hierarchical, and much less personal. In his early days, everyone knew everyone, there was no wide gap between officials and politicians, and he felt it was more possible to make an impact.

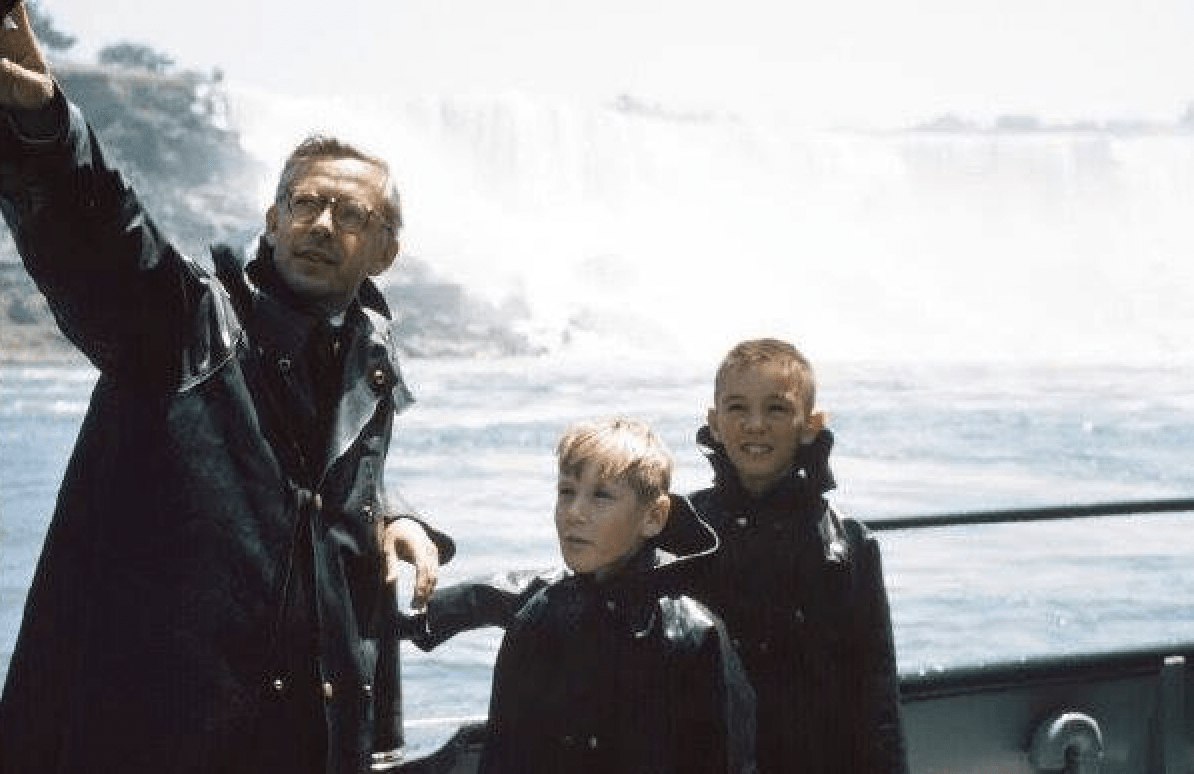

It was in Washington that I became aware of what my Dad did, and how he did it. His most obvious professional characteristic, to me, was hard work. He was indefatigable; working in the evenings, sitting in a chair in his study going over telegrams, reports, editing reports of others, writing speeches for himself and others. He remained an avid reader of history, political analysis, and novels until his death in 1999.

On Saturdays, he would take me into work at the old Canadian chancery on Embassy Row in Washington — the Canadian embassy before the Arthur Erickson landmark was erected in our prime spot on Pennsylvania Ave. — and tell me to read a book while he continued with his routine.

Dad, me and Johnny en route to Washington in 1956/Rae family photo

Dad, me and Johnny en route to Washington in 1956/Rae family photo

He enjoyed mentoring younger colleagues, who were frequent guests at our home, and appreciated, in those days, being able to work with two ambassadors who were both mentors and friends — Arnold Heeney (who had been Clerk of the Privy Council in the East Block during the war), and Norman Robertson.

The friends my father made in The Department and in the wider world were friends for life. He had a career he believed in, whose values were deeply felt, and made, with my mother, a life marked by great humour, love, and devotion that they shared in full measure with their children.

My father served as ambassador to the UN in Geneva from 1962-67, and in New York from 1972-76. It was a time when the membership in the UN grew rapidly, and decolonization was the order of the day. The economic and social structures created in the years after 1945 were being tested by the arrival of developing countries, who felt that the UN itself needed to do more to correct the global imbalance. The Cold War was in full swing, albeit with modest progress on disarmament and nuclear testing, and Middle Eastern conflict (the Suez Crisis in 1956, the Six-Day War in 1967, and the Yom Kippur War in 1973) was a constant preoccupation. Through it all, he maintained strong personal relationships with diplomats from all sides — he spoke fluent French, English, and Spanish after his tour of duty in Mexico, and knew all the senior officials at the UN well. He had the highest regard for them.

My own path to a formal diplomatic career was more circuitous. Being a student at the International School of Geneva in the 60s had a lifelong influence, and throughout my first chosen career in politics I kept up a strong interest in global affairs, both as an MP and political leader in Ontario. When the Oslo Accords were signed in 1993, we organized a reception for both the Canadian Jewish and Palestinian communities at the Ontario Legislature, and I took a delegation of business leaders to Israel, the West Bank, and Jordan. As premier, I travelled frequently to the US, Europe, and Asia, and was part of the first Team Canada mission to China in the fall of 1994.

At the family cottage in Portland, Ontario, in 1984/Rae family photo

At the family cottage in Portland, Ontario, in 1984/Rae family photo

Later, I helped set up the Forum of Federations, an international NGO based in Canada whose mission is to study and promote pluralism and better governance. Because of the circumstances surrounding the end of the Cold War, the Forum got drawn into dealing with conflict resolution and constitution-making in a number of countries, and my own work in this field took me to many places — Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria, Sudan, Kenya, the Middle East, Iraq, St. Kitts and Nevis, Eastern Europe, the UK, Spain, and, of course, the older federal countries such as the US, Canada, Germany and Switzerland. I wrote about my experiences in global governance, the perils and benefits of mediating disputes of all kinds, and saw firsthand the evolution of Canadian diplomacy around the world.

My re-election to the Canadian Parliament in 2008 led immediately to my five-year appointment as Liberal Party spokesman on foreign affairs. In 2017, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau appointed me special envoy to Myanmar and asked me to help develop Canada’s approach to the Rohingya crisis, then to humanitarian and refugee issues more broadly. On July 6th, 2020, he appointed me Canadian Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations, where I’ve taken on the job my Dad held 50 years ago.

In those days, there was no internet, social media, COVID-19, worries about climate change, brutal, kinetic aggression by Russia against Ukraine, or debates on digital divides or LGBTQ rights. The sheer volume of meetings of all kinds on these and so many other issues has exploded. The Canadian mission has expanded, now sharing a floor in a Midtown office building with the Canadian consulate in New York, and we connect by secure video conference with Global Affairs colleagues in Ottawa, and with meetings of Cabinet committees.

But some things have not changed: the public meetings of the UN are marked by endless repetition of talking points, more often than not prepared by officials in capitals whose main purpose seems to be to make sure that all boxes of strict conformity with domestic correctness have been ticked and no possible tangent left unexplored. There are contentious divides, but they are more complex. The divide between richer and poorer, authoritarian and democratic, digitally connected and unconnected, egalitarian and patriarchal, dogmatic and pluralist, climate concerned and climate complacent, the list goes on — there are many fault lines, not just the obvious ones.

Serving as Canada’s ambassador to the UN/UN Photo/Manuel Elías

Serving as Canada’s ambassador to the UN/UN Photo/Manuel Elías

Canada took its place as a middle power after the Second World War, and we have never left. What has changed is the world around us. The rise of China and other rapidly industrializing countries, the explosion of new technologies, and the presence of deeper threats, mean that our comfort level with exclusively quiet diplomacy, where white men in striped suits settle issues privately in a corner, or where nation states assume that asserting the primacy of sovereignty will somehow answer all questions, must be irrevocably thrown out the window. And it must be replaced by a firm recognition that global engagement has to be at the centre of domestic decision-making in every country, and that decision makers have to be prepared to act more coherently and quickly in real time, explaining why they are doing what they’ve concluded they have to do.

Ending gender bias, homophobia, misogyny, racism, all fears that repress people and make life so difficult for millions of human beings is sometimes falsely called “political correctness” or “wokeness”. Personal lives and careers in the foreign services of every country, including Canada, have been devastated by these terrible prejudices and it is only right that we use our diplomatic voices and policies to put them firmly behind us, and to embrace the values of equality, diversity, and inclusion.

Civil society played a key role in the creation of the UN, and the UN Charter’s preamble begins with the words, “We, the peoples of the United Nations…”. The most active engagement with public opinion requires the greatest openness, transparency and inclusion in everything we do. There is no avoiding the scrutiny and judgment of the global commons, as much as some might feel more comfortable doing business that way. Modern diplomacy is messy, confusing, often loud, and never reaches conclusions that everyone can wholeheartedly accept.

As Leonard Cohen reminded us, “There are no perfect offerings, there is a crack in everything. That’s where the light gets in.” The light is sometimes accompanied by smoke, spin, and platitudes, and some compromises are better than others, and everybody knows how disheartening some choices can be, but the search for perfection brings its own form of terror. To cut through the din of lies, disinformation, propaganda, and the equal sins of duplicity, self-serving rhetoric and an inability to make decisions in a clear and timely way, modern Canadian diplomacy has to speak with confidence, candour, humour, and honesty, and has to ensure that its acts and deeds match its words. We all know in our own lives how difficult this can be, and how we inevitably fall short of the mark.

Dad often quoted Robert Browning’s words, “Man’s reach must exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” Canadian diplomacy has not irrevocably declined, but it sometimes loses its way, its sense of its own context and history, its awareness of both its strengths and weaknesses.

Because of the ravages of a stroke suffered in his 60s, my Dad was never able to write his memoir. It was to be titled Shake Thoroughly Before Using: For External Use Only. After my first few months in New York, some brave employees, noting my tendency to shake things up a bit, sent me a plaque engraved “Hurricane Bob”. When I was appointed to this job, a reporter asked me what my father would have said.

I’m sure he would have said, “Finally. What took you so long?” And I would have answered, “I had to make a few stops along the way.”

Bob Rae is Canada’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations and a contributing writer for Policy magazine.