Meeting Mary’s Parents: Like Geese — Migratory Birds, Mated for Life

The following is an excerpt from Whit Fraser’s memoir, True North Rising: My Fifty-Year Journey With the Inuit and Dene Leaders Who Transformed Canada’s North. The book is being re-released January 31st by Penguin Random House Canada, with new material added since Mary Simon, Whit Fraser’s spouse of nearly 30 years, was appointed Canada’s first Indigenous Governor-General in 2021.

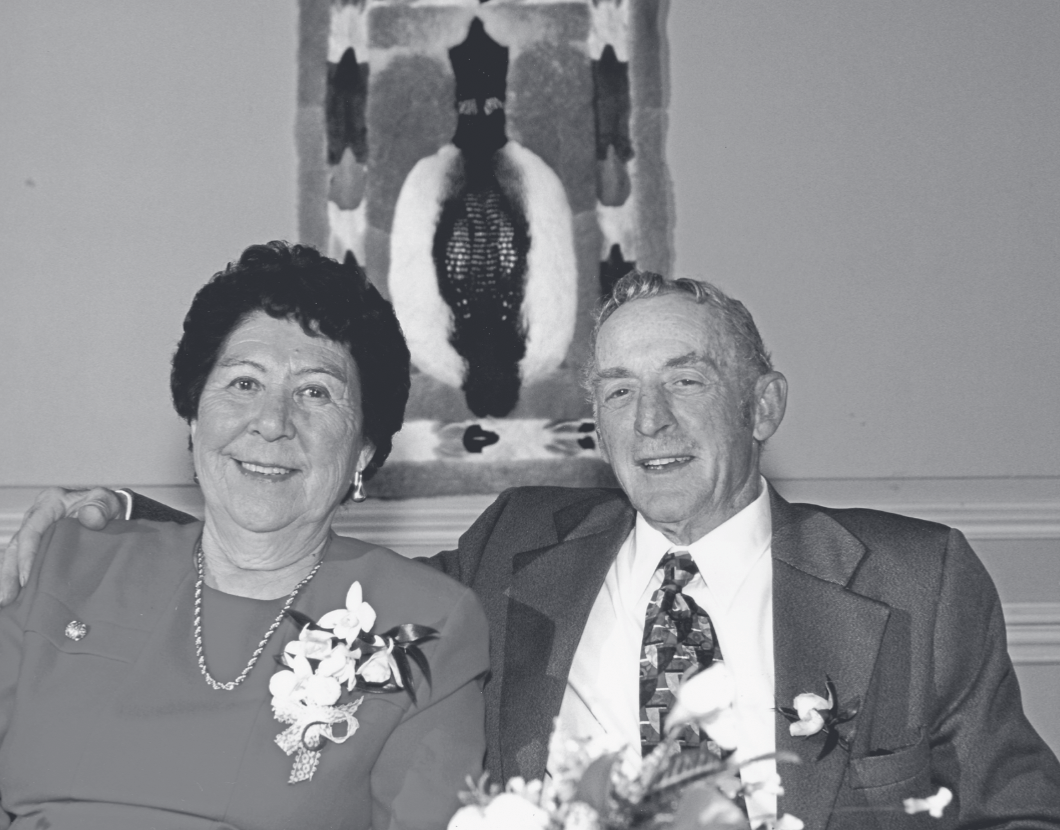

Mary Simon’s parents, Nancy and Bob May, in October 1994/Courtesy Whit Fraser

Mary Simon’s parents, Nancy and Bob May, in October 1994/Courtesy Whit Fraser

By Whit Fraser

January 29, 2023

Mary and I had been together for several months when we agreed it was time for me to “meet the parents.” Hers. You’ll recall that their lives had connected at a Hudson’s Bay post in northern Quebec. They lived most of their lives in the North. But the first time I met them was in the Arizona desert on the San Carlos Indian Reservation.

I remember turning off the main roadway, not far from the reservation’s gas station, and up a barely recognizable road. It felt like I was in the opening scene of one of a hundred old western movies.

“What next?” I asked Mary, who had the letter in her hand that Bob had mailed some weeks earlier, giving us directions and telling us how good it would be for us both to come and visit. There was no obvious road, just trails, some carved during rare periods of desert rain and flooding.

Still, Bob had written that there would be signs. Just about the time our faith was giving way to fear, we saw a white paper picnic plate pegged to a cactus with the words “Bobby Aulook” (Big Bobby in Inuktitut) written on it and an arrow pointing up what appeared to be a dry riverbed. A few rough kilometres later, another plate and another “Bobby Aulook” arrow set a new course.

There were several more of these at various points over fifteen to twenty kilometres. If someone had come along and taken one of those plates for whatever reason, we’d have been screwed. We could have found our way back to the main road, but we would never have located Bob and Nancy in the vastness of that desert of a million or more acres.

Then we crested another sandy gravel ridge, looked down through the cactus and spotted a little white trailer and a truck. Two small dots in the desert, not another manufactured object in any direction—one of several “winter camping” sites they had in the desert. The satellite dish and wood stove pipe sticking out of the camping trailer were unmistakable.

Despite their dedication to the North, each year for nearly twenty years they’d taken out a permit, to camp, fish and hunt small game near the large water reservoir that is part of the Apache reservation at San Carlos. Two or three times a week they purchased gas and food and filled their water cans at the trading post in the village. The rest of the time they stayed by themselves in the wilderness.

Bob May had come north from where he was raised in southern Manitoba at age seventeen. No one in his family was surprised when he applied to the Hudson’s Bay Company. As a kid they’d nicknamed him “Nanook of the North” because he was fascinated with that movie and had a thirst for Arctic stories and tales. After training in northern Saskatchewan, only three months short of his nineteenth birthday, he was sent to the company’s most northerly outpost at Arctic Bay on north Baffin Island, more than three thousand kilometres straight north of Montreal and even farther from his home in Manitoba. He hunted, trapped, handled dog teams, learned iglu-building, and above all, embraced Inuit values and traditions— and the language.

Bob and Nancy spoke to each other in Inuktitut even in that Arizona desert. When we were gathering firewood, his chainsaw quit working. As he fiddled and fixed it, he kept muttering to that stubborn saw in Inuktitut.

Mary’s mother couldn’t quite say my name. It always came out with a V—“Vitt.” Nancy would try over and over to get it right and break out laughing every time. I was told forming the “wh” sound is difficult for Inuktitut speakers. Given that I had butchered almost every Inuktitut phrase or word I’d ever tried, I thought “Vitt” certainly better than “Twit” and many other names I had been called.

The conversation between us moved from English to Inuktitut and the reverse, depending on who was speaking. Though I only spoke English, I was warmly welcomed into their lives and their family.

Bob and Nancy spoke to each other in Inuktitut even in that Arizona desert. When we were gathering firewood, his chainsaw quit working. As he fiddled and fixed it, he kept muttering to that stubborn saw in Inuktitut

There is, however, nothing warm in the story of Mary’s ancestors, who experienced one of the most brutal historical injustices perpetrated by the government against Inuit.

Forced relocation was the government’s answer to many realities. Sovereignty in the High Arctic in the early 1950s, or the need for an instant workforce when an airbase was built at Frobisher Bay in the late 1950s and, in the case of Mary’s relatives, a settlement at Coral Harbour on Southampton Island, where there were not enough women. Today, there is only one way to describe that practice of forced relocation. It was a cruel manifestation of colonialism. For Nancy, it’s a memory that burned bitterly throughout her life.

In 1942, a ship arrived at Killiniq. Men came off that ship, rounded up a group of young women and put them into a small boat with only a few belongings.Among them was Nancy’s Aunt Matilda, her mother’s youngest sister. Nancy said the wailing of the women coming from the small boat would never be erased from her memory.

From shore, Nancy, her mother, Jeannie, and others watched, listening to the echoing cries growing fainter and fainter as the young captives in the boat got closer to the ship waiting to take them several hundred kilometres northwest to Coral Harbour. At the same time, Inuit from other regions were being either coerced or bribed into relocating to the growing military installation there.

Though Nancy’s family had been torn apart, it speaks to their great resilience that they never lost contact with each other. At first, they relied on sporadic mail service, and much later on the telephone. Today, Mary continues to communicate with her cousins in Coral Harbour through Facebook.

But the family history is not all sad. The union of Mary’s parents is a real love story, one I have heard them tell and one I have retold many times. It starts in Killiniq or, as the settlement was known to nineteenth-century whalers, Port Burwell, at the entrance to the Hudson Strait where Labrador and Quebec meet. The harbour there is quite protected, and there are still abandoned wooden whaling boats hauled high on the shore. Only a few of the old buildings remain, but at different times it was a trading post, whaling station, missionary residence, RCMP detachment, government administration centre, weather station and Coast Guard port.

The teenage Bob May was on his maiden Arctic voyage when his ship stopped in Port Burwell on a July day in 1937. When he got off to stretch his legs, he noticed a group of young Inuit children, all girls, shy and laughing and very much intrigued by this strange Qallunaaq with striking blue eyes and red hair. He motioned for them to come closer and reached into his pocket for a pack of gum. He offered each child a stick, knowing that in that place and that time, this was a great treat. The kids knew it too. They took the gum and ran away laughing. One girl, maybe ten or twelve, captured his attention—she had an incredibly beautiful smile.

At each stop Bob’s ship made at the coastal communities of Labrador and Baffin Island—Lake Harbour, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet and some other outposts, now long abandoned— the Hudson’s Bay superintendent on board decided who among his group of new recruits appeared most suited for that particular post. By the time they approached Arctic Bay on the northernmost coast of Baffin Island, Bob was the last apprentice on the ship, and Arctic Bay was the end of the line — he had reached his destination.

Mary and Whit having lunch on Ungava Bay, 2010/Courtesy Whit Fraser

Mary and Whit having lunch on Ungava Bay, 2010/Courtesy Whit Fraser

He would spend two years there, and another three years at Port Harrison (now Inukjuak), on the east coast of Hudson Bay in northern Quebec.Then in the early 1940s, Bob was promoted to post manager and relocated to Kangiqsualujjuaq, or George River, a post at the mouth of that great waterway.

Being a manager carried some perks, among them the authorization to hire a full-time cook and housekeeper. Inquiries were made, and soon he hired the highly recommended Jeannie Angnatuk. She arrived at the post with her youngest daughter, Nancy, who was now about sixteen or seventeen. Bob immediately recognized Nancy as the child with the beautiful smile he’d noticed on the grassy banks of Port Burwell. Fortunately for him, Nancy had been equally struck by his mesmerizing blue eyes. It was love at second sight. Neither ever gave details on just how long it took for what happened next to happen. But it did, and the lives they lived together would fill another book.

In 1948, Bob took an Inuit child suffering from appendicitis 230 kilometres by dog team across the Ungava Peninsula in the bitter cold and heavy snow to rendezvous with an RCAF crew. Upon reaching Fort Chimo, they were both flown to Halifax, where surgeons saved the boy’s life. Another time Bob and Nancy’s kids were out gathering eggs. Mary was on a ledge, her small hand gently finding its way into the nest of a gull or kittiwake. Johnny was with her and would have been about twelve. He was hunting and when a duck flew past him, he swung his shotgun around quickly. He did not intend to shoot anywhere near Mary on the cliff, but two pellets ricocheted off the rock and pierced her lower jaw, lodging in her face and tongue. She didn’t fall, but she was instantly in pain and bleeding heavily.

Mary’s mother and grandmother gathered her up, carried her to the tent, and laid her down on her bed of spruce boughs and eiderdown blankets. Johnny had disappeared. That evening, using the high-frequency radio, they managed to contact Bob, who was with a hunting party farther down the coast. They were all concerned about internal bleeding or infection or any one of a dozen other complications. It took Bob more than two days to get back, and for most of that time, Johnny would not come back to the camp. He had convinced himself that if he hadn’t already killed his sister, she would soon die, and he would be to blame. Finally, his grandmother was able to persuade Johnny to come and talk to Mary through the tent wall. When Johnny heard that she could still talk, he began to calm down.

When Bob got back, he wrapped his daughter in blankets and put her on a mattress in the bow of his open twenty-foot freighter canoe—the workhorse of the northern waterways, powered by an outboard motor—and they set off across Ungava Bay. The trip took more than fourteen hours, and for every minute of that trip, Bob gripped the throttle and tiller. One bay after another, from headland to headland, sometimes aided and other times hampered by some of the world’s highest and constantly shifting tides, they moved closer to the base at Fort Chimo. Mary remembers the pain from the constant banging of every wave. Other times, she was in a complete daze.

When they made it to the clinic, the nurse—there were no doctors—judged it might be better to leave the pellets in place rather than risk additional damage by trying to remove them. Mary rested and healed for a few days, and then father and daugh- ter made the return trip back across the sixty kilometres of the bay, though this time at a pace that was a little less hectic.

One of my favourite stories from Mary’s childhood is about the full year the family spent in the bush at what locals call the “big bend” of the George River. Mary was sixteen. Her father had left the Hudson’s Bay Company and was planning to build a hunting and fishing lodge. Soon after the ice cleared, he and Nancy headed upstream with all their children, along with Jeannie, Mary’s grandmother.

One of my favourite stories from Mary’s childhood is about the full year the family spent in the bush at what locals call the ‘big bend’ of the George River. Mary was sixteen.

They lived in two tents—sturdy, bell-shaped canvas tents sewn at home. The tents were large enough to stand and walk around in, with wood stoves for warmth and cooking. They lived almost entirely from the land, picking berries, catching fish, hunting caribou and gathering eggs. The children amused themselves playing Inuit games and at night listened to legends and tales that always contained a subtle message of good over evil and right over wrong—just as fairy tales do, in cultures everywhere.

It was a lonely Christmas that year, “so far away from civilization that even Santa couldn’t find us,” as Mary once described it. Christmas morning arrived and there were no presents. Strangely, she said, her father insisted on going outside now and again, to walk a big circle on the frozen river. Around noon, he said to them all, “Listen, do you hear it?”

They rushed outside and looked skyward to see a single-engine bush plane approaching. It circled and then landed. To the children’s joy and surprise, the pilot was an old family friend. He stepped out of the plane laden with fresh oranges and candy for all. Her dad had been making circles in the snow to guide the plane to a safe landing spot on the frozen river.

Mary still talks about those times a lot. Sometimes, during a speech or presentation, when she wants her audience to better understand the context of Inuit cultural perseverance, she will speak about her life in the bush. It’s always so very clear that her own strength grew from watching the example of Jeannie through that long and bitterly cold winter, going night after night with little sleep because she was stuffing more firewood into the stove to keep everyone warm. The air on the other side of the thin canvas walls would routinely drop to minus forty. Mary says, “I remember sleeping with my hat on or covering my head under the blanket to keep warm. Every day was a constant battle just to stay alive.” She also says that her destiny was shaped in that tent on those cold winter nights.

I remember watching her face during one magical moment in her term as Canada’s ambassador to Denmark. We were attending the inauguration of a new culture and performing arts centre in Nuuk, Greenland. The Greenland Inuit are famous for their singing and a choir of men and women was giving us a magnificent performance. Mary was dabbing her eyes with a tissue, and I knew that she was back in that tent on the frozen bank of the George River on one of the nights when her grandmother would turn the dial on the old battery-operated shortwave radio, searching for Radio Greenland, and suddenly the tent would fill with the beautiful voices of a Greenlandic choir singing both traditional Inuit songs and ancient European classics translated into Greenlandic Inuktitut. She remembers her grandmother telling her, “Listen, Mary. Those are our people. We are all the same, one nomadic Arctic people.”

If Mary’s destiny was shaped living on the land, it was the schoolyard and the classroom that forged her drive and commitment to social justice and equality. It was also shaped by the strength and love of her parents, Bob and Nancy.

I still remember those two sitting in our Ottawa living room holding hands. In their seventies and eighties, they would stop for a visit on their annual spring return or fall migration to Arizona. They’d be sitting there together, and Bob would look lovingly at his wife and sweetheart of some fifty years, get a gleam in his eye, then reach into his pocket and offer her a stick of gum. She would giggle and take it.

They are still side by side, in the cemetery at Kuujjuaq. Seven of their children are still living in Kuujjuaq, all holding key positions in the community. Two of the sons are among the best-regarded bush pilots in the region. Then there’s Mary.

Excerpted from True North Rising by Whit Fraser. Copyright © 2023 Whit Fraser. Published by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.