Managing the Relationship: The Bilateral Best and Worst

At the tip of a very large iceberg of diplomats, bureaucrats, customs agents, border guards, ministers, secretaries and other Canadians and Americans whose livelihoods depend on our bilateral relationship sit two leaders: the prime minister of Canada and the president of the United States. Each of those leaders brings to the relationship their own predispositions, knowledge and temperament. As veteran political strategist Robin Sears writes, it hasn’t always been a meeting of minds.

Robin V. Sears

Mackenzie King’s appallingly sycophantic expression of high praise for Adolf Hitler following their meeting in 1937—“He is really one who truly loves his fellow men,” among other horribly misplaced verbal garlands—cost him the trust of both the British monarchy and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His expression of admiration for the Nazis so chilled Roosevelt’s view of King that it took time to rebuild trust in him as a wartime ally. Despite public shows of support, the Roosevelt White House developed a back channel in the run-up to and the early months of the war in passing messages to King George VI and to Winston Churchill. It was Canada’s Governor General, John Buchan, also known as Baron Tweedsmuir and bestselling author of the thriller The Thirty-Nine Steps, who was very close to King and functioned as an intermediary. King apparently never knew the depths of White House mistrust. Buchan died following a stroke soon after the war started but the mistrust lingered.

John Diefenbaker so badly bungled the management of what became the “Bomarc Missile Crisis” that it contributed to his defeat in 1963. Diefenbaker first accepted the deployment of the new American missiles in North Bay and LaMacaza Quebec, then tried to hide the fact that they were fitted with nuclear warheads, then rejected them. Understandably, first the Eisenhower then the Kennedy White House saw this as a little rich, as Canadians had permitted nuclear-armed American bombers to protect Canadian airspace for the previous decade.

Lester Pearson, who as Canada’s senior diplomat won the Nobel Prize for his calming of the Suez crisis, antagonized the Johnson White House. As prime minister in 1965, in a highly undiplomatic speech at Philadelphia’s Temple University, Pearson attacked US plans to bomb North Vietnam. That prompted Lyndon Johnson to explode days later at Camp David, berating Pearson with a classic bit of Johnsonian rage, “You don’t come into my living room and piss on my rug!”

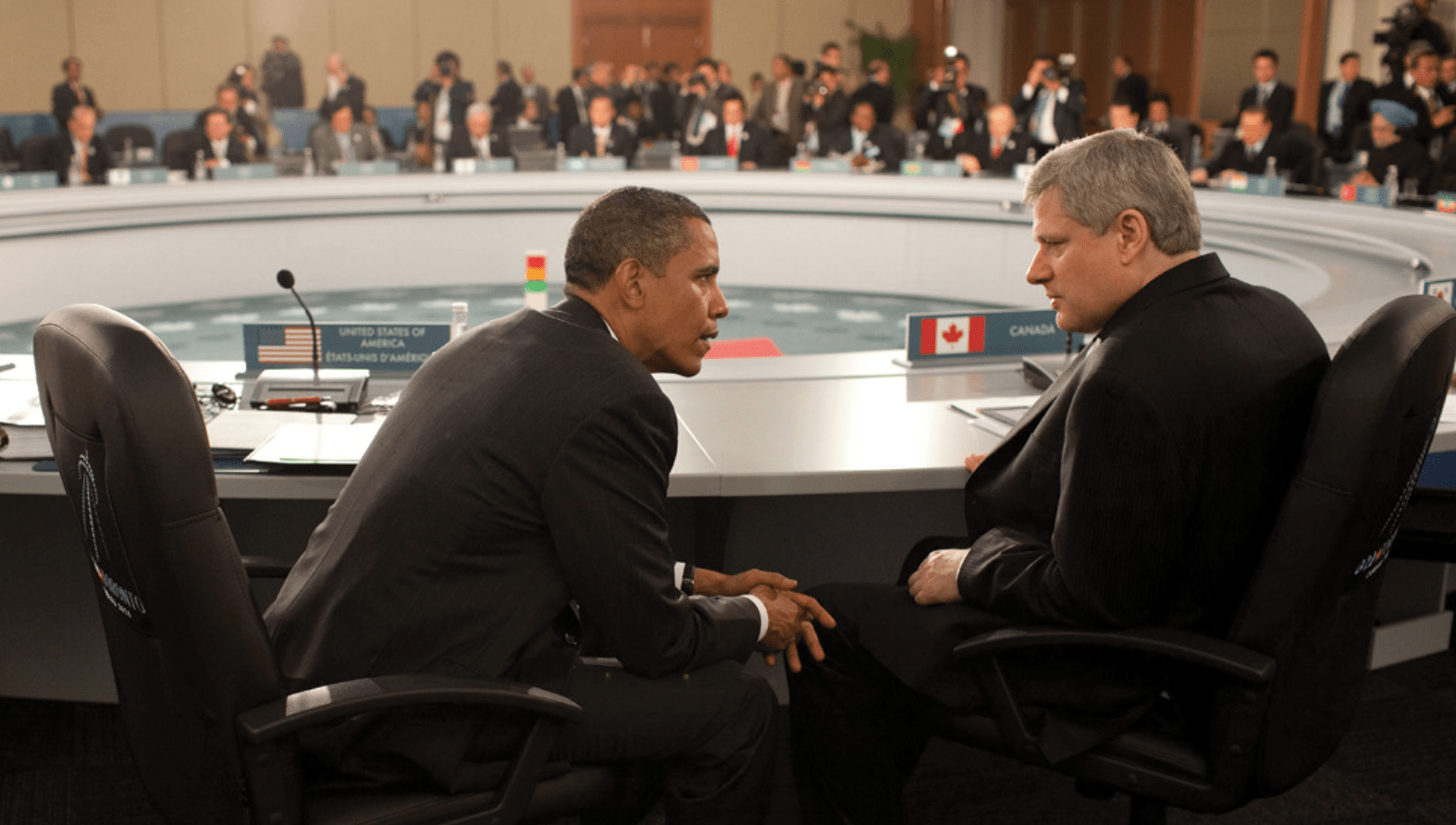

The defence offered by supporters of both Dief and Pearson was that the Canadian people were angry and demanded action in both cases. More recently, Stephen Harper sat across from Barack Obama for six years from 2009-15, seriously misjudging Obama’s opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline, calling the file “a no-brainer.”

Not good enough, Brian Mulroney—the master of White House management in the past century—would say. He likes to remind incoming Canadian prime ministers of a perennial truth, that the two most important files on the desk are first, Canadian unity and security, and second, the relationship with the White House. Managing relations with the premiers is your first obligation and managing relations with the White House is your second. He often adds that ensuring that the American president’s door remains open, opens every other door in Washington.

Mulroney’s mastery of this reality helped him win the 1991 Acid Rain Treaty from the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. Avoiding the skeptical American stance on acid rain, he quietly began applying greater and greater pressure behind the scenes. It would have been a great deal more politically successful for him with Canadian voters if he had, instead, whacked the Americans publicly, harshly and often.

Herein lies the core of the delicate balancing act that Canadian prime ministers must always aim to achieve. Canadians’ sanctimony and finger wagging at American failures is one of our less salubrious national characteristics. The Canadian snowbird soaking up the Hawaii or Florida sun in her winter retreat sees no irony in snarling, “Damn right!” as she reads another gratuitous attack on American vulgarity, racism or tragic devotion to guns; “Bloody Americans!”

I confess to being one of the millions of Canadians who suffer from this same reflex. We love American culture, story-telling, and often buy American products online from American websites when there are comparable Canadian options available. But at the same time, we cannot resist sneering at America’s overreach or—most notably under the last president—its often obtuse treatment of close allies, including us.

The problem with succumbing to this temptation is that we are not equals. We do not have the clout to demand anything from the world’s most powerful nation. We need to co-operate, negotiate and inveigle. Our chronic battles over salmon and softwood lumber are not likely to ever end, they can only be relentlessly and delicately managed. Canadian prime ministers’ access to the White House permits us an almost unique opportunity to offer tough and potentially difficult messages in private. Take it public and that access will slowly close. Chrystia Freeland, counselled regularly by Mulroney, used this wisdom to pull off a new NAFTA agreement against what looked like impossible early odds.

Most Canadian prime ministers have bobbled their White House management at one time or another, but no one holds the gold medal for bungling Canada-US relations at the highest level more deservedly than Pierre Elliott Trudeau. We may be grateful that this is one of his father’s weaknesses that Justin Trudeau has rejected. Although he struggled in his relations with Donald Trump—who wouldn’t?—the current prime minister has managed three consecutive presidents with far greater deftness than his father handled his.

Pierre Trudeau’s personal history helped to lock him into patronizing and dysfunctional relationships with at least three of five American presidents during his tenure. His relationship with Gerald Ford was limited, with Jimmy Carter mostly positive. Educated to revere European enlightenment values, a follower of left-wing critics of American foreign policy, his anti-American instincts were enhanced by his experiences as a world traveller before his political career began in 1965. Trudeau saw the adverse impacts of America’s support for a bizarre collection of anti-Communist dictators on their own people in Asia, for example.

Soon after his election, he took the bold decision to recognize what was then known as Red China. He had signalled this intention in the 1968 campaign, to considerable skepticism. Negotiations were tense and difficult, but in October 1970 Canada recognized the Beijing regime. Second only to the United Kingdom’s earlier decision, it was huge affront to American foreign policy diktats at the time. It has never been clear whether the White House was taken unawares with no pre-briefing on Canada’s imminent move, though in a way it opened the door for Nixon’s landmark visit to China in 1972, seven years before the US recognized the PRC.

Care in managing the White House would have required a private phone call to the American president. Some American experts on the Nixon White House insist it did not happen. Whether a signal was sent or not, it is clear that Trudeau made little effort to soothe the famously thin-skinned American president. The relationship with Nixon never improved, with the Watergate tapes recording Nixon asking an aide to “get me that asshole Trudeau” on the line. When asked to comment, Trudeau replied: “I’ve been called worse things by better people.”

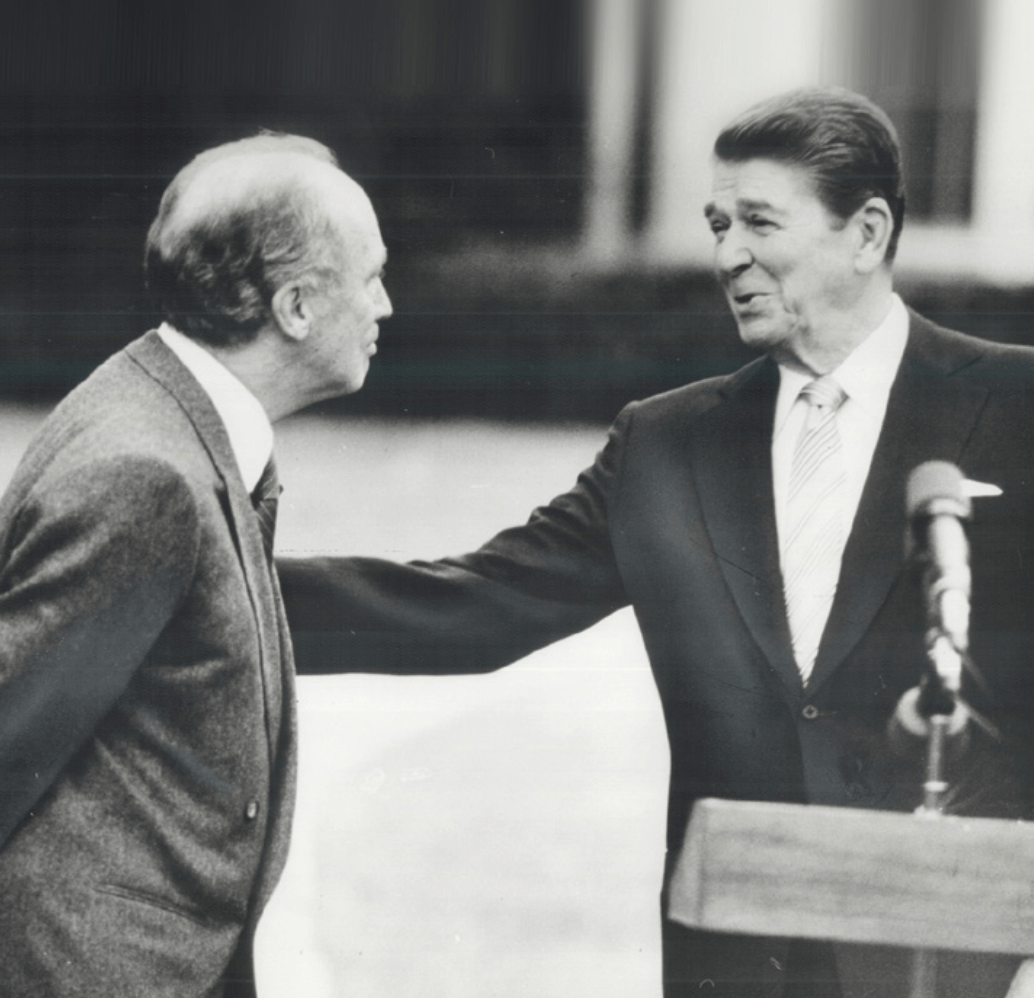

His relationship with conservative Ronald Reagan was more contentious. After several earlier clashes, Trudeau’s pre-retirement disarmament mission was the final collision. His global “peace initiative” was greeted with some bemusement by several leaders, given Trudeau’s presumption that he should lecture them about how to speed détente. It put him sharply at odds with Reagan. That tension was clear during a confrontation at the 1984 G7 in London, only days before Trudeau’s retirement.

A leaked State Department recording of that encounter made clear that Trudeau was again in lecture mode, blaming Reagan for the failure to restart disarmament talks with the Soviets. Reagan reacted with exasperation, saying that the US had “offered everything” to attempt to draw the Moscow back to the table. Asked about the leak on his return to Ottawa, Trudeau said that the State Department were “liars” and, again, demanded that the Americans do more to advance disarmament.

Brian Mulroney, then opposition leader, had declared following Trudeau’s announcement of his magical mystery tour that, “Our pride in Canada should not obscure the hard realities of superpower existence, nor should such pride give rise to illusions of influence beyond bounds that can only disappoint and confuse.” It was a good forecast of the project’s impact, as it quickly slid into insignificance following Trudeau’s departure from office.

Trudeau was an estimable Canadian prime minister whose legacy includes many epochal achievements, from ending racist immigration policy, to wrestling separatism to the ground, to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. How much more might he have achieved for Canada on trade and procurement, for example—the subject of his first battle with Nixon—if he had only resisted his impulse to patronize and offend Americans?

Would quiet pressure on Vietnam have yielded more progress toward peace, or later, on the bloody civil wars in Central America? Questions for future historians and

biographers.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears, a former national director of the NDP and later Ontario’s representative to Asia based in Tokyo, is an independent communications consultant based in Ottawa.