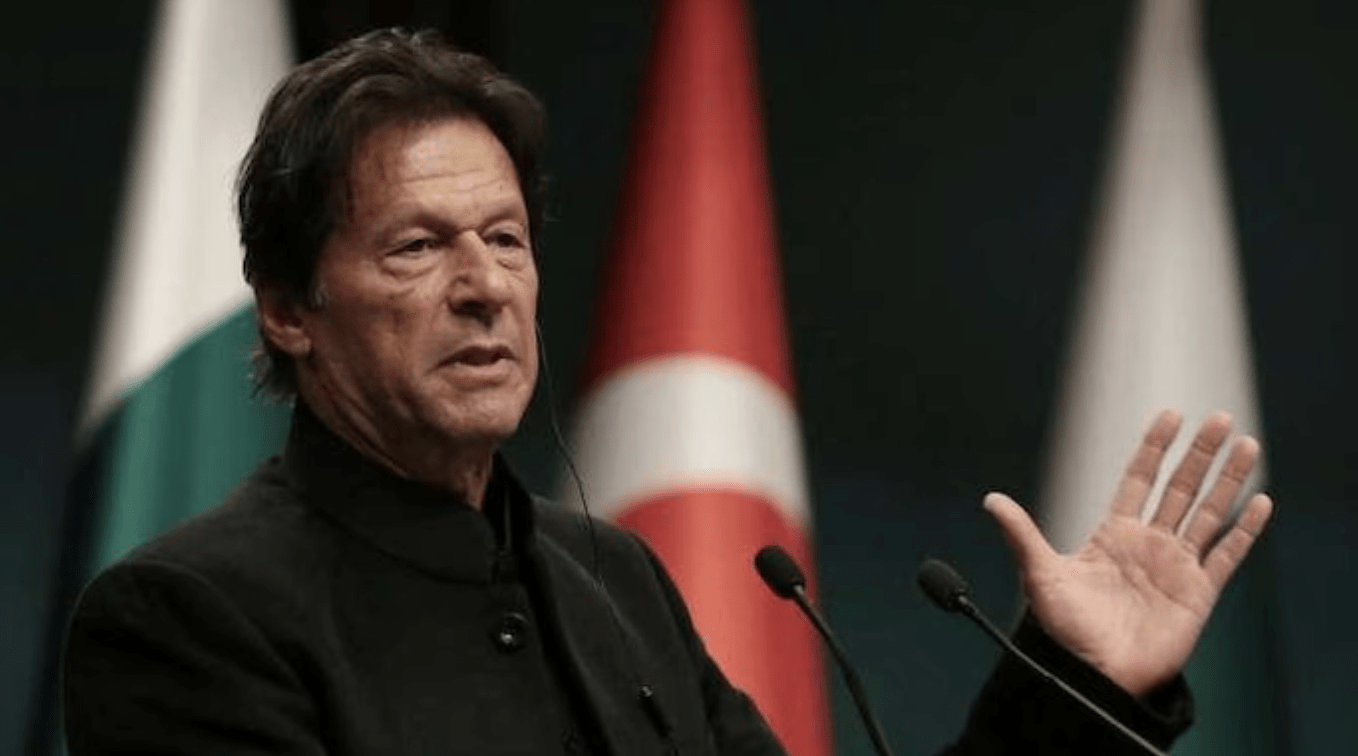

Letter from Pakistan: How a Jailed Imran Khan’s Popularity Continues to Confound his Enemies

AP

AP

By Kathy Gannon

November 29, 2024

In Islamabad this week, tens of thousands of supporters of jailed former Prime Minister Imran Khan invaded the tree-lined streets of the most heavily protected section ‑ the red zone ‑ of the federal capital.

It was no easy feat for them to get there. The army and police were also present in the thousands, amid a security lockdown in the country, internet blackouts and blockades of major roads leading to the capital to repel the demonstrations.

But the protesters, led by, among others, Khan’s wife, Bushra Bibi, used raw numbers and heavy vehicles to remove massive shipping containers piled three deep. They pushed past police and military barricades. Many were from Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, where Khan’s party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf Party (PTI or Justice Party) still rules.

The protest was originally promised to last until Khan was freed. But after a violent assault on protesters that left scores injured and as many as eight dead, as well as five security personnel, the protesters went home.

Still, the protesters’ show of support for Khan, a former star cricketer with a glamorous pre-politics lifestyle, once married to British journalist and screenwriter Jemima Goldsmith, returns him to the global spotlight. More significantly, it speaks volumes about the changing state of Pakistan’s politics.

For some, this is about the popularity of Khan himself. But for many, it is also about rejecting a system they have long felt has ignored and abused them.

Khan’s quiet acceptance of jail, and refusal to request or make deals for his release, has garnered him support, even among those who worry about his sometimes-extreme religious views. When in power the 72-year-old angered women’s rights groups with comments that suggested women’s dress was to blame for increased assaults.

When Khan was ousted, back in April 2022, his popularity was iffy at best, but it soared after a no-confidence vote removed him from power. Largely orchestrated by a military, frustrated with Khan’s increasing independence, it returned to power the country’s tired and largely discredited past politicians.

The army chief at the time, Gen. Qamar Jawad Bajwa, all-but admitted to the army’s role in Khan’s ouster, which Khan said was done at the behest of the United States. America flatly denied the charge, though Washington most likely didn’t mourn his ouster.

Khan was a major critic of America’s war on terror and images of him shaking Russian President Vladimir Putin’s hand on an official visit to Moscow the day Russia invaded Ukraine didn’t help his standing with Washington. In fairness to Khan, his trip was planned months earlier, but the U.S. expressed its outrage.

But much more important than what America thinks, at home in Pakistan, the frustration people feel about a political landscape dominated by corrupt dynastic politics, an interfering army and relentless disrespect, had been creeping toward anger. That discontent now would seem to be bordering on fury.

Pakistan’s military has ruled the country for much of its 77-year history, either directly or indirectly. The army in fact helped bring Khan to power in 2018 just as it orchestrated his predecessor, Nawaz Sharif’s ouster. The rift between the military and its chosen politicians usually begins when the politicians start to act like they actually run the country and dare to defy the army’s wishes.

For some, this is about the popularity of Khan himself. But for many, it is also about rejecting a system they have long felt has ignored and abused them.

Take the current rulers, the Sharifs and the Bhuttos. Neither the late Benazir Bhutto, who was assassinated, in 2007, nor her father, who was hanged by a military ruler, were favorites of the army but twice she was returned to power with their help and twice ousted, also with their help. Nawaz Sharif was a favorite of the army until he dared to challenge their rule and was ousted. Bhutto’s son, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, is former foreign minister and chairperson of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Both he and his father, president Asif Ali Zardari, remain active power players in the country’s coalition government. During his wife’s rule, Zardari, was tagged Mr. 10 percent, a reference to the alleged kickbacks he would charge companies wanting to do business in Pakistan.

The military opened the door for Imran Khan, but after three years, Khan began to behave as if he could make decisions independently of Gen. Bajwa, the army chief. Now, the Sharifs are back, though instead of Nawaz, it is his brother Shehbaz Sharif as prime minister and his daughter Maryam as chief minister of the country’s most powerful and populous Punjab province. Zardari is president of Pakistan.

Even if today’s political leadership in Pakistan looks like yesterday’s – dominated by the Sharifs and the Bhuttos and run by the army – it is a different Pakistan.

In the February election that followed Khan’s ouster, which the military and its political allies sought to manipulate, Khan’s supporters won a major victory. Even as Khan’s party was not allowed on the ballot, independent candidates representing his party, on a platform of challenging the army in politics and holding the corrupt accountable, won big.

It was a first for Pakistan.

The electorate, which has always been politically savvy, has also been resigned to the status quo, and an arrogant leadership has written them off as uneducated, and easily manipulated.

But no more in this different Pakistan, in large part because of a younger generation, more widely educated at home in post-secondary institutions and while connected to the world via smartphones, rooted in their country rather than abroad. The time is gone in Pakistan when post-secondary education abroad, an exclusive domain of the elite, defined Pakistan’s educated. .

Today in Pakistan universities have proliferated. Where in 2000, there were about 1 million post-secondary students, in 2020 there were nearly 5 million, and they have expectations. Analysts say they are also more political. But it is also the 30- and 40-year- olds, generations of Pakistanis who are frustrated with the lifestyle of the rich and corrupt and with a military they increasingly see in a similar light.

In February, Gallup Pakistan published an interesting election-day and post-election-day survey which said: “Turnout among youth rises considerably in 2024; PTI (Khan’s party) popularity among first time voters and relatively educated segments made it the highest vote-puller in the country.”

It went on to say 31 per cent of voters voted for the PTI (as independents) followed by the Sharifs’ party, which took 24 percent of the vote.

While political manipulation and rigging has characterized most past elections in Pakistan, social media and an explosion of local media shone a bright light on the seat-stealing this time around.

Added to the changing mix in Pakistan is a more aggressively independent judiciary that has in the past given cover to military rule and bowed to the powerful. But it, too, is changing. In a rare show of defiance, five judges signed a letter demanding the military and its intelligence wing stop trying to influence court rulings. Judicial rulings also challenged a suspect Election Commission.

The judiciary, like Parliament, is still weak after successive bouts of military rule, but while it might be one step forward and two steps back, it is now going forward.

Mostly, the recent headlines reflect the fact that the people want more. They are demanding respect from their leaders, and that their rights and their needs be recognized and met.

But fundamental to the changes in Pakistan is a desire – and increasingly a demand – that future elections be decided on how well the country’s politicians perform for the people, rather than on how well they perform for themselves and the country’s military, or “other power.”

Kathy Gannon covered Pakistan and Afghanistan for The Associated Press for 34 years. She authored the book I is for Infidel. You can read her regular posts on Substack.