Letter from Johannesburg: In a Country Transformed by Corruption, Mandela’s Legacy Lives On in the Streets

The author with volunteers, including fellow booksellers, in downtown Jozi/Griffin Shea

The author with volunteers, including fellow booksellers, in downtown Jozi/Griffin Shea

By Griffin Shea

May 29, 2024

It’s impossible not to notice the Rissik Street Post Office. The four-storey Victorian building fills half a block, with a clock tower that looks over Johannesburg’s historic core. Behind it, high school kids play basketball on a court surrounded by brightly coloured murals. Facing it; the Gauteng provincial legislature and — across the expanse of Beyers Naudé Square, named for an Afrikaner anti-apartheid activist — the landmark Johannesburg City Library.

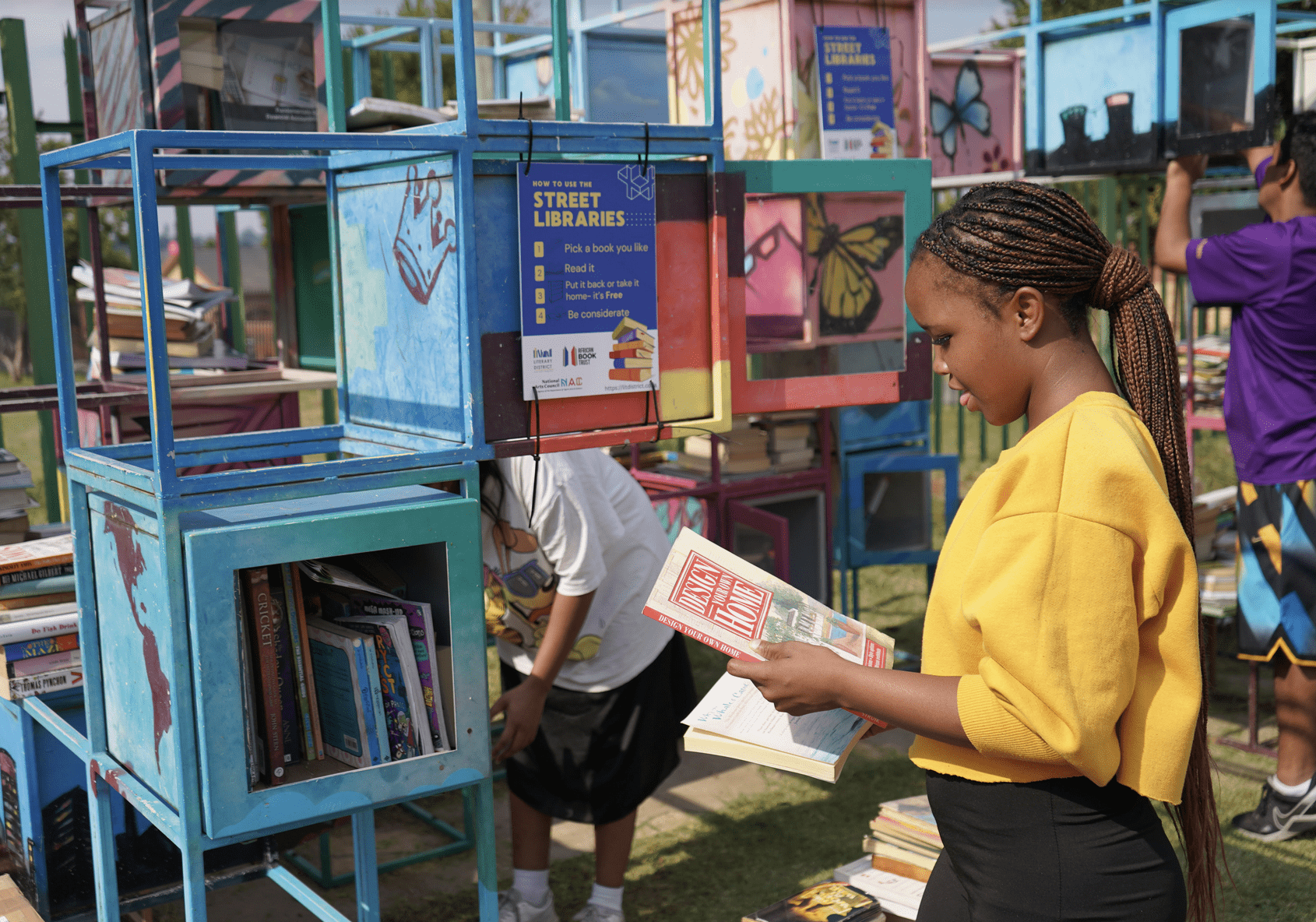

I moved to Johannesburg 16 years ago to take a journalism job with a news agency. Through a series of mid-life reinventions, I now also own a bookstore, Bridge Books, among more than 70 booksellers in the city’s Literary District, not far from the Rissik Street Post Office. We do regular bookish activities – readings, signings, workshops. But we also do a lot of community engagement, largely funded by local and national government. At the moment, we have 62 employees, many working in the neighbourhood parks in addition to our three stores and two street libraries, in Soweto and Alexandra.

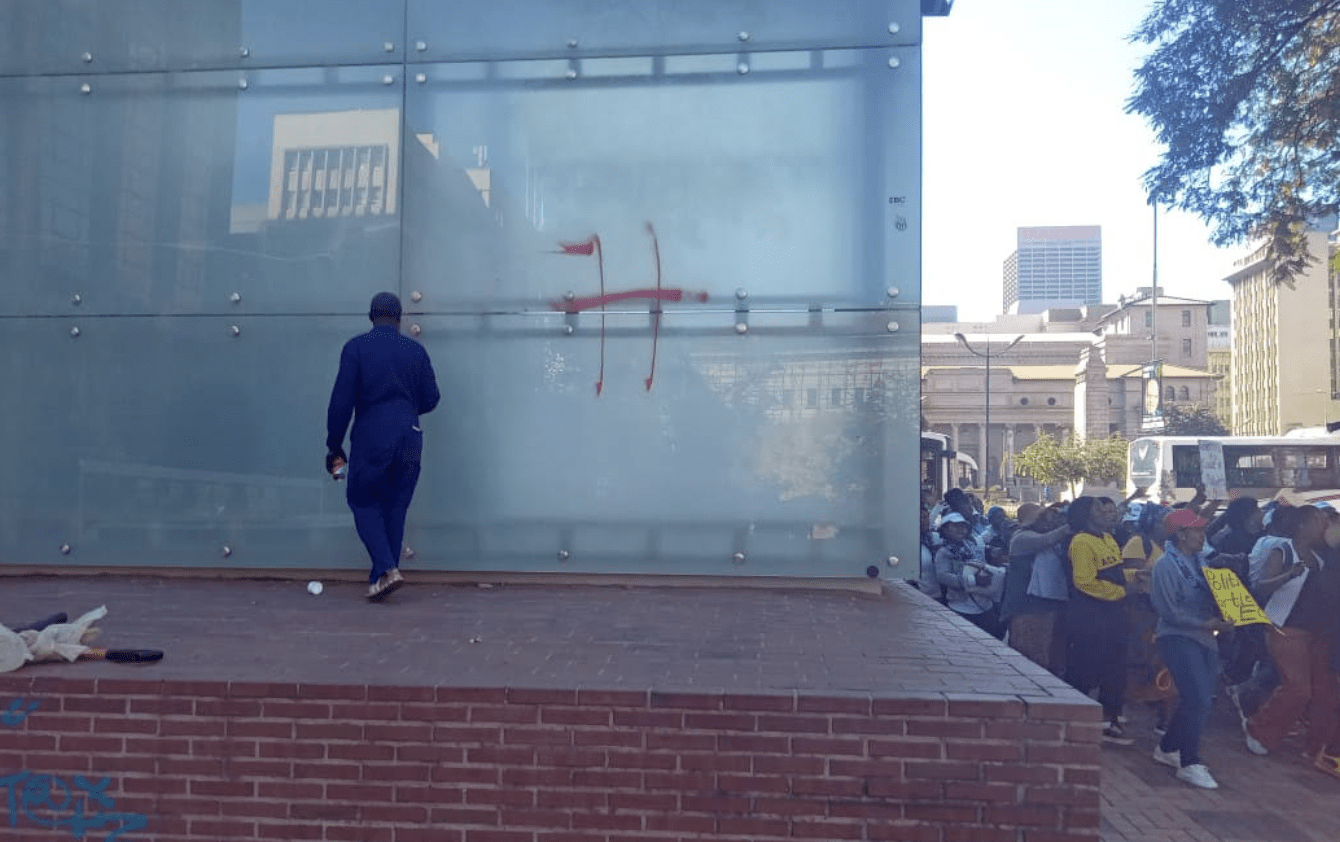

A Bridge Books worker erases election graffiti beside a rally/Griffin Shea

A Bridge Books worker erases election graffiti beside a rally/Griffin Shea

The Rissik Street Post Office, built by the city for the national South African Post Office, which in 1996 declined to renew its 99-year lease, has been officially empty for nearly three decades – almost as long as South Africa has been a democracy. The bells in the clocktower were stolen in 2002, presumably sold for scrap. A fire gutted it in 2009. The South African Post Office is now in bankruptcy proceedings. The last letter I received was in December, a Christmas card sent from the United States. The sender had dropped it in a mailbox in 2022.

Around this time last year, I started noticing the Rissik Street Post Office for the wrong reasons. The smell wafting from it was becoming unbearable. Every city has its odors, but this was the unmistakable – and worsening – smell of sewage.

It seemed fitting for a building that has become an ornate monument to a city’s dysfunction within a country trapped in a cycle of corruption that became so potent under the presidency of Jacob Zuma, it inspired the term “state capture”, meaning the machinery of government had effectively been bought off by wealthy business interests. The state freight rail company Transnet carries less and less every year as tracks and trains aren’t maintained. The tax department was hijacked, the national airline went bust, and the anti-corruption cops were defanged.

With Ramaphosa’s election in 2018 came promises from the ANC to turn things around and re-instate the ANC’s Mandela-era legacy of pluralist democracy and trust in government. Instead, South Africa still feels besieged.

Since 2009, Johannesburg has had nine mayors. Three died in office, but the others fell to the inter-party feuding that happened after the African National Congress (ANC) lost its majority in city hall.

That’s the scenario the entire country faces after Wednesday’s elections. While President Cyril Ramaphosa is expected to be re-elected, the ANC is forecast to lose its majority in parliament for the first time since it took power in 1994, when Nelson Mandela became president in a historic, euphoric end to apartheid. And, depending on how low the ANC’s numbers sink, South Africa could face the national version of the cocktail of corruption and shifting alliances whose political paralysis the people of Johannesburg have suffered through for a decade already.

But as the ANC wrestles with an increasingly distant and degraded Mandela political legacy, the generations inspired by Mandela’s belief in the power of service maintain that legacy in the streets of the city where he started his legal career, faced trial and was sentenced to life in prison.

As has been pointed out by a range of international agencies and experts, corruption is a major threat to democracy — a phenomenon on display in the past two decades across datelines and continents as private and foreign investment have flipped stable democracies into the “failed state” and “illiberal” columns of global governance rankings.

With Ramaphosa’s election in 2018 came promises from the ANC to turn things around and re-instate the ANC’s Mandela-era legacy of pluralist democracy and trust in government. Instead, South Africa still feels besieged. Zuma went to prison for a bit, for defying a court order in his corruption trial. The courts have also blocked him from running in this election, due to that conviction. Yet many of Zuma’s besties remain in high office. Ramaphosa’s hands suddenly seemed less clean when burglars made off with about $500,000 that was stuffed in the couch cushions at his farm. He says the cash was from selling his prized cattle.

Cleaning the Rissik Street Post Office/Griffin Shea

Zuma is now leading a new party, the MK, whose support the ANC may need to stay in power once the results of Wednesday’s election are confirmed. They could also turn to another ANC offshoot, the Economic Freedom Fighters, a Marxist party led by former ANC Youth League President Julius Malema. The largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, prides itself on running Cape Town and Western Cape province effectively. But they’ve run a tone-deaf campaign that’s deepened their image as a white-dominated outfit.

The worry is that however a coalition is formed, it will prove as unstable as the ones that have run Johannesburg. South Africa has never had to have a coalition government, so there’s no muscle memory of how it might be done.

Meanwhile, the Rissik Street Post Office provides a lesson in the practical results of political instability.

The city began renovating the building before the pandemic, but during the lockdown, construction ceased and squatters moved in. Some divided the space into tidy apartments and devised a cleaning schedule for the bathrooms and corridors. In another wing of the building, less community-minded people bashed through windows, stole doors from the hinges, and began defecating on the floor. That was what caused the smell wafting out into the street.

As the ANC wrestles with an increasingly distant and degraded Mandela political legacy, the generations inspired by Mandela’s belief in the power of service maintain that legacy in the streets of the city where he started his legal career, faced trial and was sentenced to life in prison.

We started to worry about the public health issue, so, our staff mobilized for a month to scrub out the building. In the process, we got to know the squatters. Many were unemployed, so we were able to give them jobs through the government program that sponsors most of the Bridge Books community workers. The pay is dismal and the work part-time, so they each earn about $125 a month in Canadian dollars.

But over the last year, Someleze has saved up enough to buy a used sewing machine, which he’s used to start a custom fashion brand, designing athletic leisure wear that he sells on Instagram. Simphiwe has used the money to start up a small business cleaning sneakers, a high-demand service in a young and fashion-conscious city. Others used their work experience with Bridge to get jobs in publishing, social media marketing, and retail. In a country with 40% unemployment, these victories matter.

And, at a time when government can’t be relied on to fix things, citizens and the private sector have stepped up and in. Insurance companies have started providing marshals to repair potholes and direct traffic at intersections where lights haven’t worked in years. A coalition of businesses has started installing solar lights on long-darkened city streets and across the landmark Nelson Mandela Bridge. Various groups of residents and businesses collect garbage, provide neighbourhood security, and maintain parks.

It’s not that nothing gets done in Joburg — people are simply filling the void when things get stuck, because the government is often the sticking point.

A Bridge Books street library in Soweto/Griffin Shea

A Bridge Books street library in Soweto/Griffin Shea

That wasn’t always the case. When I arrived here in 2008, everything felt possible. The country was getting ready to host the soccer World Cup. That came with white elephant stadiums, but also new airports, new train lines, and a surge of public pride. Violent crime, while horrific, was falling. The ANC-dominated parliament fired President Thabo Mbeki, which felt like an overdue correction for his AIDS denialism.

But what Johannesburg also shows is that things can keep moving. If society can’t work with government, it can work around government. Inside the civil service, there are still many people who just want to get on with their work, whether that means getting trees planted in parks or training young people for jobs.

Increasingly, there’s a recognition within local government that they can get more done working with the public, whether that’s businesses or community groups or individuals.

At Bridge Books, we’ve proposed adopting the nearby parks and taking over the Rissik Street Post Office to turn it into a community centre for arts, sports and jobs training. I’m not sure how we’ll pay for that, but every day it’s clear that we have plenty of committed staff, volunteers and neighbours who want to make it work.

Griffin Shea is a former foreign correspondent for Agence France-Presse. He is the owner of Bridge Books, which includes three stores in Johannesburg, street libraries in Soweto and Alexandra, and a range of community development projects. His literary activism includes a Bridge Books program to publish lost South African classics banned under apartheid. Follow at Bridge Books and @bridgebooksjozi.