Letter from Hong Kong: The Limits of Democracy (China’s Version)

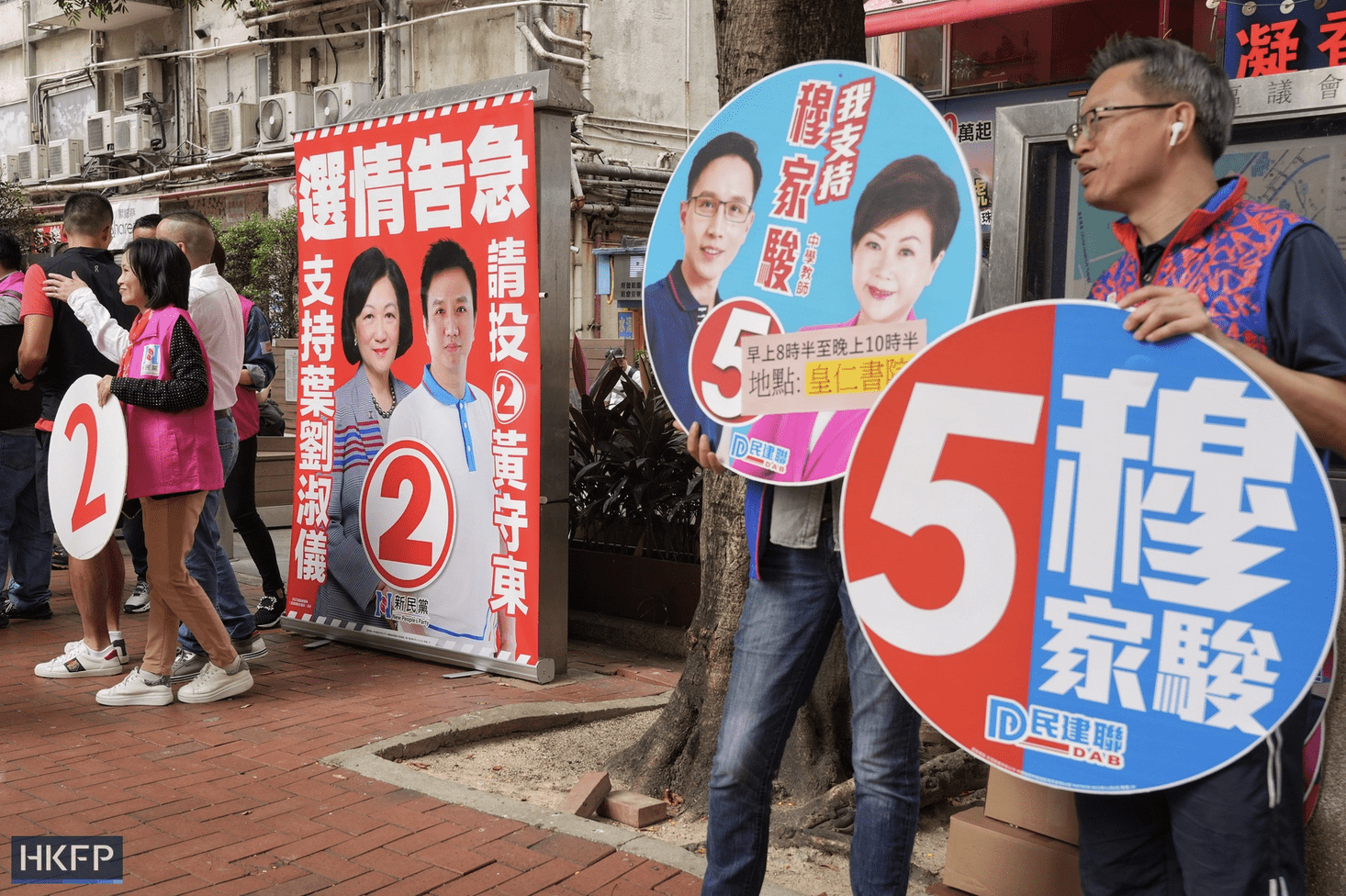

Canvassing in Tin Hau for Hong Kong’s first, China-controlled ‘patriots-only’ District Council election, on December 10, 2023. Photo: Kyle Lam/HKFP.

Canvassing in Tin Hau for Hong Kong’s first, China-controlled ‘patriots-only’ District Council election, on December 10, 2023. Photo: Kyle Lam/HKFP.

Robin V. Sears

December 14, 2023

HONG KONG — As the Beijing-imposed “patriots-only”, opposition-free District Council elections here in Hong Kong proved this week, voters won’t vote if you make a mockery of their franchise. The first elections since China’s 2020 security capture of the former British protectorate and Beijing’s subsequent democracy-choking electoral overhaul were all-but boycotted.

The last District Council elections in 2019, which included pro-democracy candidates, pulled in 71.2 % of the electorate — the highest turnout in history, producing a landslide for the democrats — whereas the December 10th Beijing-curated version drew 27.5%, the lowest turnout ever.

“Many citizens may view these elections as unfair or illegitimate, because authorities have chased out, intimidated, disqualified, shut down or jailed opposition leaders and parties,” University of Hong Kong professor emeritus John Burns told CNN. “Many citizens may view participation in the new arrangements as useless or a waste of time.”

What did China expect from Hong Kong, whose affection for democracy has been an element of its global brand for years? These days, discerning the connections among Beijing’s expectations, its actions and their apparently unintended consequences has become a whole new Hong Kong parlour game. The official response to these logical lapses has been to frame failure as success. John Lee, the current Hong Kong chief executive and latest in a string of inept puppets handpicked by Beijing, praised the election turnout. The “resistance,” Lee said in a flourish of autocratic ventriloquism, came from “people who have been rejected by the system because they are not qualified or they do not subscribe to the same principle which is patriots administering Hong Kong.”

Elections in all 18 District Councils of Hong Kong are held every four years. These are the local elections of the city’s 470 councillors who handle what The New York Times described as “unglamorous tasks such as dealing with pest infestations, overflowing trash and illegal parking”, as opposed to the 90-member Legislative Council, or LegCo, Hong Kong’s parliament, which enacts laws, appoints judges, and manages budgets. Both bodies have been targets of China’s internationally condemned political cleansing campaign of harassing, purging and jailing pro-democracy politicians and replacing them with pro-Beijing quislings in a bloodless takeover that has pre-empted by decades China’s agreement under the 1997 handover of Hong Kong from British rule, which promised 50 years of democracy and human rights.

Forty years ago, when one arrived in Asia’s only global city and wandered around the core business district, it would feel much the same as the heart of any major metropolis: huge towers above, crowded streets and sidewalks below. Until you turned a corner and gazed at a long queue of distinctive black Rolls Royces, their drivers idling away the long wait for their bosses.

Then, a sideways glance would reveal a glimpse of the contradictions of this city, jarring to behold. Pushing heavy metal trolleys piled high with used cardboard and other junk over a cobblestone street alongside the Rollers would be a tiny, ancient Hakka Chinese woman, protected from the sun by a massive woven hat, struggling to persuade her cart up the hill. Today, the Rolls have largely been replaced by $300,000 Mercedes Maybachs, but the struggling Hakka women remain.

Still, much has changed, none of it good for the people of Hong Kong. While the vibrant city long synonymous with money and moxie seems to be in the middle of a transformation to just another massive Chinese conurbation run with an iron fist, like Shanghai, Guangzhou or Shenzhen, Hong Kong is different.

President Xi has acknowledged publicly several times how essential Hong Kong remains as a fountain of Western cash. Hundreds of billions of dollars a year flow each way — through the city to the world, and from foreign investors into the mainland. As China has become less welcome in the world’s other two financial centres, New York and London, Hong Kong’s financial importance to Beijing has grown. However, angry public debates rage about how long this will be true.

While human rights and democracy in Hong Kong have been targeted for years by China through legislative encroachment and political corruption, some freedoms remain. But to this longtime fan of Asia’s most fascinating city, it now appears that China really did not know what it was doing when it tried to cow the city under an Orwellian security regime. Among other assumptions, Beijing apparently thought that by throwing out highly popular, ‘unpatriotic’ pro-democracy legislators, journalists and teachers, dissent would inevitably wane over time.

These days, discerning the connections among Beijing’s expectations, its actions and their apparently unintended consequences has become a whole new Hong Kong parlour game.

Not so far, and it has been almost four years since the whip came down through China’s 2020 security law. Not only does the CCP have no experience at real democratic governance at the national or regional level, their one effort at the village level descended into corruption and nasty conflict among the residents and was dropped. As an authoritarian regime, the nuances of municipal governance don’t much interest China except as a corruptible means to an end. For example, Hong Kong citizens may agree not to criticize your battering of the local media. But when a water main bursts and threatens to poison an entire neighbourhood with sewage, the difference between democratic governance and its opposite suddenly becomes germane. In China, tales of poisoned water taking years to resolve are commonplace. Hong Kongers can still raise hell about incompetence. To some observers, exercising this prerogative seems to be growing. The hapless new “patriot” councillors will soon learn the price paid in isolation by officials who toe the party line but have little power to affect change.

For now, the security commissariat has won, both in Beijing and Hong Kong. But their clampdown is coming with ever-higher costs. The exodus since China imposed its security law has been stunning. Half a million residents have left since the beginning of 2021, including 291,000 in the first half of 2023. What makes this serious is who is leaving. The thousands fleeing to Canada, the U.S, Australia and the U.K are the educated, the middle class and the affluent, the professionals and their entire families.

A dear friend here astonished me recently by revealing she had made plans to move her children, her siblings and her ailing mother to Australia after a lifetime in Hong Kong — a city she admitted she loved more than any. Asked why she had made such a fateful, and clearly painful, choice, she looked at me sharply and said, “I can no longer live with the stress and fear of the late-night knock on the door…” This middle-aged, well-educated and reasonably affluent Hong Konger is no radical. She is precisely the type of citizen no community would want to lose.

The erratic and arbitrary security police have another blow to the city to answer for: the slow outflow of investment banks, and the lawyers, accountants, and consultants who serve them. These are the commercial heart of this city. If the trickle becomes larger and more public Hong Kong’s sad future will have been set. A recent survey from the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce (HKGCC) showed that more than 60% of businesses expect no income growth next year, with 20% of those anticipating a decrease in income. This month, Moody’s downgraded the city’s credit rating from stable to negative on political uncertainty grounds and based on its economic links to the mainland, provoking rage from the government and Beijing.

So, herein lies the conundrum for China. It can loosen the handcuffs on the city somewhat, learn to listen, and thus successfully manage the city’s essential role in keeping foreign investment flowing through Hong Kong. Or, if it sees that as too risky, it can scramble to find other ways to keep Western capital flowing into and out of the city. Given President Xi’s continual meddling with foreign investors’ rights, this seems unlikely. The likely consequences of any Plan B are already obvious in China itself. Next year, it is predicted that as much at $50 billion of private, mostly family capital, a month, will flee. Even an $18 trillion economy cannot afford to lose $600 billion dollars a year for very long. Nor will Hong Kong.

If the CPC hardheads prevail, this city will become a satellite city to its neighbour, Shenzhen, now more than twice its size. It was a fishing and farming town of fewer than 50,000 when this visitor first saw it. The Hong Kong Government is massively funding the construction of a new city connecting Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

All these surface contradictions and anxiety-provoking stresses now being felt by many Hong Kongers, however, disguise what a seasoned western diplomat here describes as “the parallel public and private faces of Hong Kong people.” Publicly, most still smile at a passing police officer, avoid public conversations about anything resembling politics, and try to present an unthreatening face to their masters. Privately, many let rip their anger at the efforts to break the will of Hong Kong people. This ‘soft resistance’ is in many citizens’ DNA. Guangzhou people — the province from which most Hong Kongers came — has centuries of resistance to the emperor in its history. Hopefully, the heavy physical labour that the poor, and the indomitable Hakka women, must do to survive will soon be history. But some things won’t change.

Forty years ago, a sunset viewed from Victoria Peak, known locally as just “The Peak”, looking down on the golden harbour and a city blazing in lights, and across to the beaches, parks, forests and mountains beyond, was one of the great urban vistas in the world. The sunsets and the city’s vast array of great museums, galleries and the best restaurants in the world will endure. The beauty of its setting and the resilience of the city’s amazing people will all still be permanent treasures of Hong Kong, no matter how badly the CPC bungles its management.

Veteran political strategist and Policy Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears lived and worked in Tokyo as Ontario’s Agent General for Asia for six years, and later worked in the private sector in Hong Kong for a further six years.