Lessons from D-Day for a World Order in Peril

Infantrymen going ashore from the HMCS Prince Henry, June 6th, 1944/PO Dennis Sullivan-LAC

Infantrymen going ashore from the HMCS Prince Henry, June 6th, 1944/PO Dennis Sullivan-LAC

By Colin Robertson

May 31, 2024

June 6, 1944 changed the course of the Second World War. Even Josef Stalin, who had long complained about the West’s failure to launch the second front, was moved to remark of D-Day, “The history of war has never witnessed such a grandiose operation. Napoleon himself never attempted it.”

Early on that Tuesday morning, Allied troops from 13 nations swam, ran and leopard-crawled their way onto the sand and stones. For more than 14,000 Canadian soldiers, their objective was securing a 10-kilometre stretch of Normandy beach that the Allied command called Juno.

Supporting them offshore was the greatest armada in world history, including Canada’s contribution of 10,000 sailors and 124 warships of the Royal Canadian Navy, including HMCS Haida, ‘the fightingnest ship’ in our navy. Amphibious landings are the most complex and risky of military and naval combined operations and for weeks allied navies were the cord connecting the fighting troops to the food, ammunition and armaments conveyed across the Channel.

Flying overhead were bombers, fighters and gliders, including 39 fighter and fighter-bomber squadrons of the Royal Canadian Air Force. They would also drop 450 Canadian paratroopers.

By the end of the ‘Longest Day’, 359 Canadians had been killed, among 1,084 Canadian casualties. By the end of the Normandy campaign, more than 5,000 had died. By war’s end, more than one million Canadians wore a unform and more than 43,000 were killed. For a nation of just under 12 million, it was a consequential sacrifice.

The Canadian War Cemetery at Bény-sur-Mer/Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Canadian War Cemetery at Bény-sur-Mer/Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Many of those who died in the Normandy campaign are buried in the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery that I visited in 2007. Touring the beach, the bocage and then visiting the cemetery left me in awe of the Allied effort and filled me with pride in the Canadian contribution.

I toured the battlefields with Canadian historian Terry Copp as part of an expedition organized for schoolteachers by Historica Canada. Supported by Veterans Affairs, it was a modest but useful investment ensuring that future generations of Canadian students would learn and remember a time of Canadian heroism and sacrifice – the price of keeping our liberties.

While we now take the victory for granted, it was an extraordinary feat of planning and execution. As Copp explains:

“The seemingly impossible victory was the product of Allied success and German failure at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. There is not much controversy about strategy. The German generals as well as Hitler persuaded themselves, with some help from Allied deception schemes, that the main Allied attack would take place in the Pas de Calais and they held to the view until late July-early August, forcing a limited number of German infantry divisions to fight an attritional battle with diminishing resources…At the operational level, the Allies devised an approach to battle that minimized their weaknesses and maximized their strengths…At the tactical level, the German doctrinal commitment to the immediate counterattack by whatever forces were available allowed the Allies to plan brigade- and battalion-level actions in the sure and certain knowledge that the enemy would come at them as soon as possible.”

If the United States was the ‘arsenal of democracy’ then Canada, said Franklin Roosevelt, was its ‘aerodrome’, training more than 130,000 Commonwealth and allied aviators at bases across the nation.

Our merchant mariners and the Royal Canadian Navy were instrumental in winning the longest battle of the war, that in the North Atlantic, shepherding convoys of food, fuel, men and armaments to beleaguered Britain. It was the situation that most troubled Winston Churchill. By war’s end, Canada possessed the third largest navy, a tribute to our shipbuilders and recruitment capacity, and a reputation for having acquitted ourselves admirably in battle.

Our hard-power prowess earned us a voice and a seat at the tables designing the post-war order. Our diplomats understood the relationship between hard and soft power and leveraged both accordingly. Having lived through two world wars, experiencing the collapse of order, they did so conscious that war is the decider in international politics.

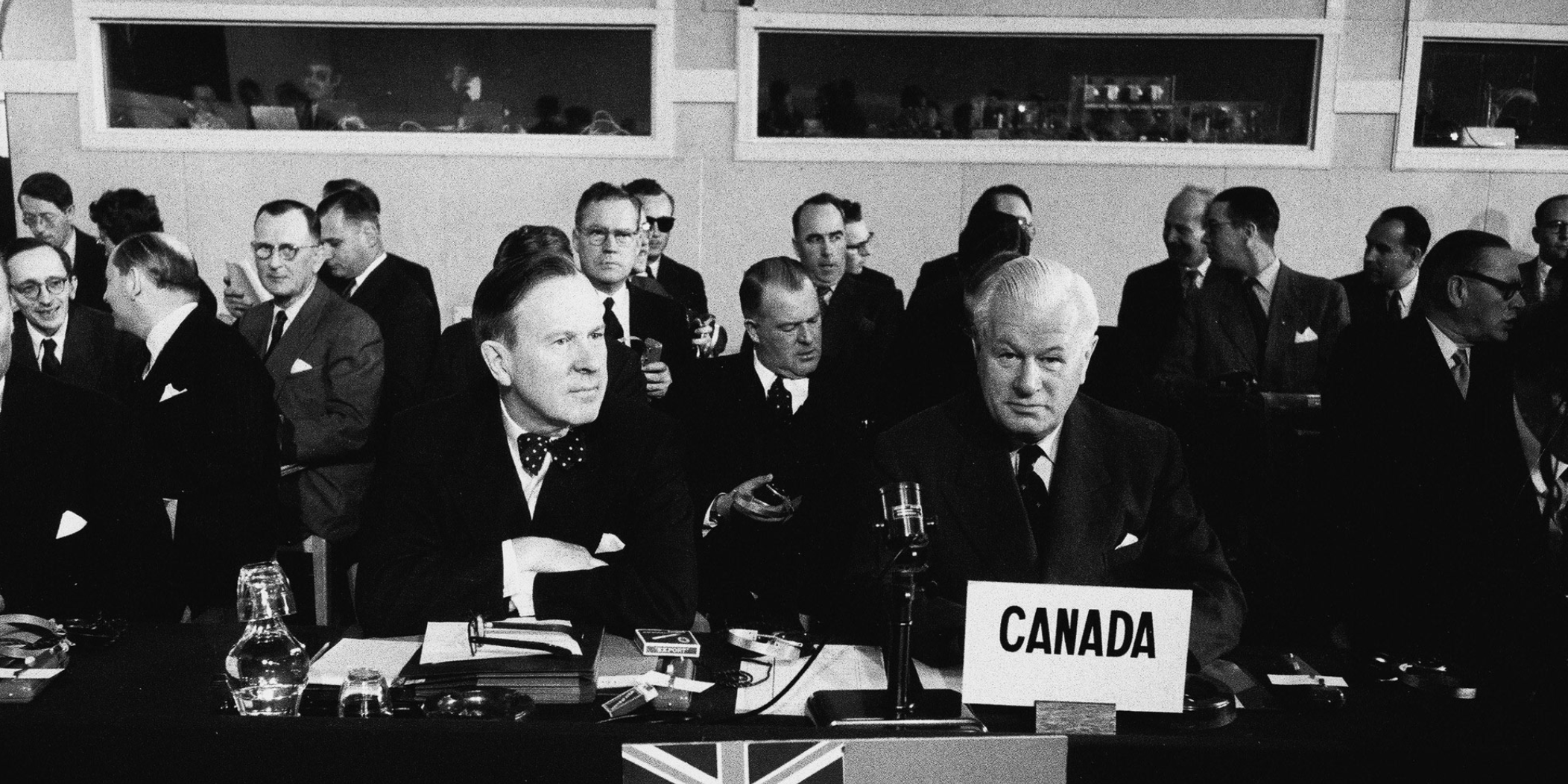

Canadian Foreign Minister Lester Pearson (L) at Germany’s accession to NATO/NATO archive

Canadian Foreign Minister Lester Pearson (L) at Germany’s accession to NATO/NATO archive

Their vision of Canada was that of a middle power – a bridge and helpful fixer – but it was premised on a strong military capacity. In practise, this meant a strong contribution to NATO and a strong contribution to NORAD. They recognized that the world is a brutal and violent place.

They became the diplomatic engineers to the American architects, in creating the multilateral institutions: the United Nations in San Francisco and the IMF and World Bank at Bretton Woods and then the alphabet soup of functional agencies that continue to serve humanity. They practised diplomacy but they knew that the deterrent force created through the NATO alliance was essential.

Remembering and learning about the past matters. It gives us context for what is happening today and a sense of how to prepare for tomorrow. History does not repeat itself but there are rhythms to human behaviour.

In scale, in destruction and in the huge number of casualties, the Second World War is once again a historical reference point. After it was over, we said ‘Never Again’.

Yet, once again, we are engaged in a war in Europe. The international situation is in turmoil. Revisionist and revanchist forces would return us to a world of spheres of influence where might makes right. We know from history that this will not work for us.

This is why it is vital to study and remember lessons of past experience, including the old Roman adage: “If you want peace prepare for war.”

While the tide of freedom is ebbing, we now recognize we cannot export democracy. But where we see people prepared to fight to be free, as in Ukraine, we should help, just as we did 80 years ago. And we need to keep doing it.

We need to remember that the Canadian tradition in global affairs is not just being the honest broker, the multilateralist convenor and everyone’s best friend. In 1939 Canada stood up. We put real military power on the line. It’s a reality that we haven’t faced for 80 years. But it is here again.

So, as we remember, we also need to act.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.