Lessons for King Charles, from Sovereigns Shakespearean and Not

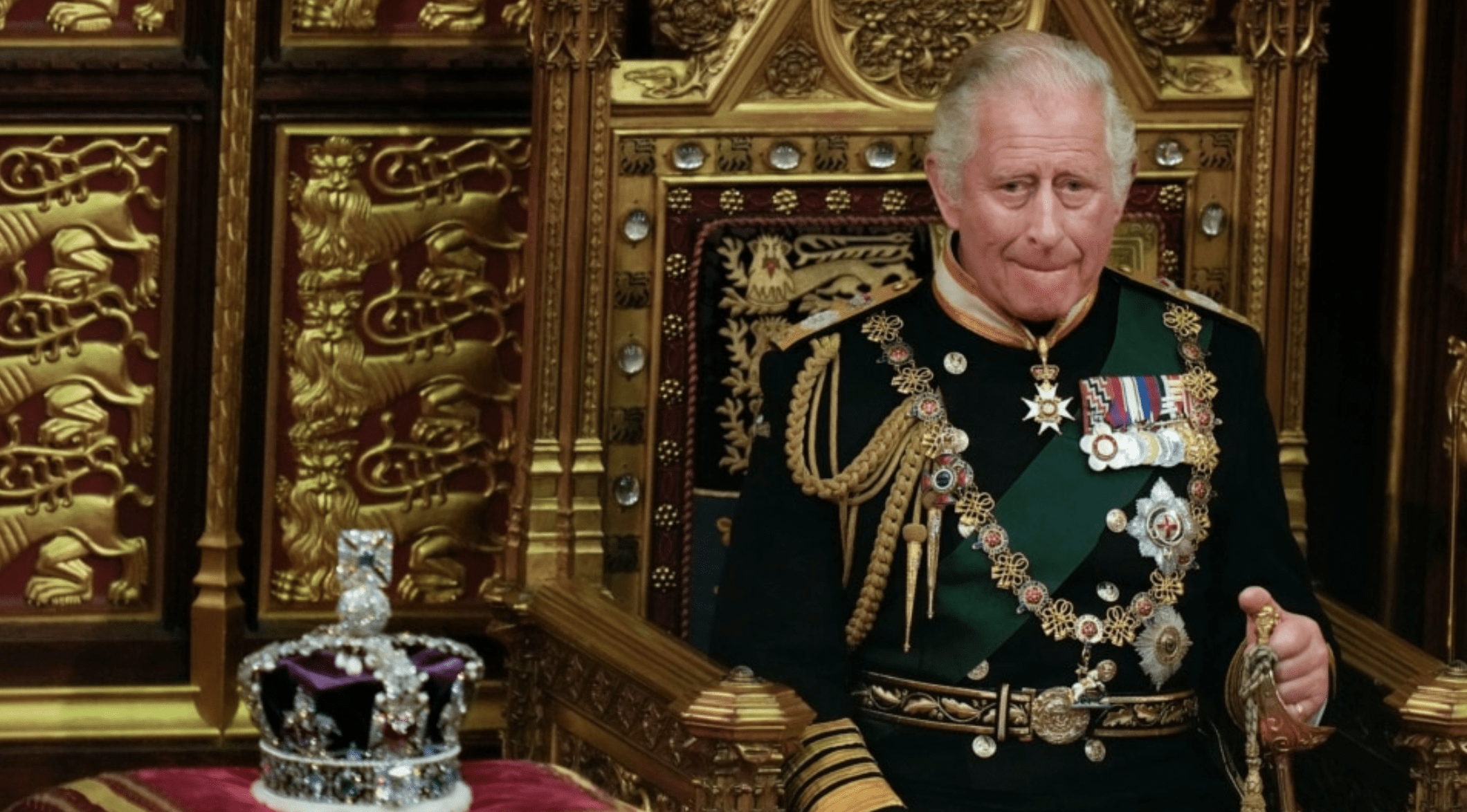

AP

AP

The presence of a king engenders love

Amongst his subjects and his loyal friends,

As it disanimates his enemies.

William Shakespeare, Henry VI Part I

Lisa Van Dusen

September 10, 2022

Of all the lines of Shakespeare devoted to kings and kinging, the Duke of Gloucester’s advice to King Henry VI is among the least grisly: No Macbethian delusions of power consolidation through body count; no spiralling Lear-ish psychosis; none of the scheming and plotting of a vindictive Richard. Just a quick BTW on bonus points for showing up.

Alas, if all it took were showing up for a king to disanimate his enemies, Shakespeare might have spent his career in Warwickshire panto.

While the world continues to mourn the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, her legacy of leadership is beginning to crystallize. Among the many qualities attributed to the Queen by those who loved, knew, worked with, encountered and observed her were those of duty, authenticity, integrity, stoicism, humour, decency, kindness, empathy, dependability and wisdom. For any mortal to check two out of ten on that list in a good week is an achievement. For a human being to evolve across a lifetime in the public eye while managing to consistently embody all of those qualities may be unprecedented. Gratitude for that example — not for being perfect, but for making it look easy to be better — may partly explain the outpouring of appreciation expressed since her death.

The one word we haven’t heard since the Queen died, in all the remembrances, anecdotes and unscripted commentary, is “ego”. While fulfilling a role that has been, historically, sufficiently fraught with hamartic hubris, megalomania and judgment-skewing narcissism to have plausibly filled the dramatic canon of the greatest writer in the English language, Queen Elizabeth somehow managed to firewall her core identity from the ego distortions of both lifelong power and global celebrity. She glided like a galleon through the daily life of history — from speech to audience, from hand to hand, from caber toss to Mariachi band — one monarch to whom The Bard would’ve given a wide berth for lack of drama, annus horribilis notwithstanding.

Perhaps the Manichaean crucible of the Second World War through which her father reigned gave the Elizabeth the perspective to care about the right things, even in this sometimes ridiculously complex century she left behind. The Queen seemed, for seven decades, the antithesis of the line from Shakespeare’s fourth Henry, “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

She glided like a galleon through the daily life of history — from speech to audience, hand to hand, caber toss to Mariachi band — the one monarch The Bard would’ve given a wide berth for lack of drama, annus horribilis notwithstanding.

The conflict crucible King Charles faces is less kinetic and less straightforward than 20th-century existential strife. Contemporary anti-democracy warfare is waged — the authoritarian invasion of Ukraine aside — in the propaganda sphere, through hybrid and narrative warfare, by weaponized corruption and by the kind of sabotage-from-within that President Joe Biden recently deplored for plaguing American democracy.

The British monarchy, as an invaluable source of soft power for a flagship democracy, has been a target of that brand of narrative warfare for more than a decade. King Charles has had some experience with the sort of tactics — covert, corrupt and performative — that have disrupted major events since 2016, when a corrupted Brexit referendum and the most off-putting presidential election in US history suddenly besieged the public sphere with chaos following the relative normalcy of the Obama years.

Whatever enemies Queen Elizabeth had, they were of the philosophical and political variety — from the Irish Republican Army during the height of The Troubles to the cyclical fluctuations of broader, anti-monarchist republicanism — rather than personal. That distinction has been made many times over in the reaction to her passing. But as anyone whose life has been hijacked by the invasive, covert larceny of 21st-century narrative warfare can attest, it is as personal as a Shakespearean revenge plot.

The King may need to adapt to both his new role and the daily abrasions and eye-rolls of modern, weaponized intrigue even before he has mastered his grief. Meanwhile, channeling his mother’s sense of perspective may not disanimate the bad actors, but it certainly couldn’t hurt.

Policy Magazine Associate Editor Lisa Van Dusen was a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.