Less a Leadership Race Than an Identity Crisis in Progress

There are moments when it’s hard to fathom that Pierre Poilievre and Jean Charest are vying to lead the same party.

Global News

Global News

Lisa Van Dusen

May 26

The Conservative Party of Canada leadership race is adhering to the Newtonian laws of political physics in ways the last federal election campaign did not.

The 2021 election campaign can be recalled as the trajectory of Justin Trudeau as he justified the campaign while attempting to remain in motion while fending off the chaos of external forces from Afghanistan to anti-maskers while attempting to swipe the momentum from Erin O’Toole with a lot of help from Erin O’Toole.

The Conservative leadership race is more linear, but in a way that is more about the party than the candidates. This is entirely understandable given the timing, the forces at play and the evolution of the federal Conservatives from the Progressive Conservative Party last observed in its traditional incarnation under Brian Mulroney through its merger with the Canadian Alliance through the Harper years through its recent identity crisis.

That identity crisis has played out in the repeated failure of what was a national party to recapture that viability under its two post-Harper seat-warmers, largely based on the irreconcilable pressures of social conservative orthodoxy and national electability.

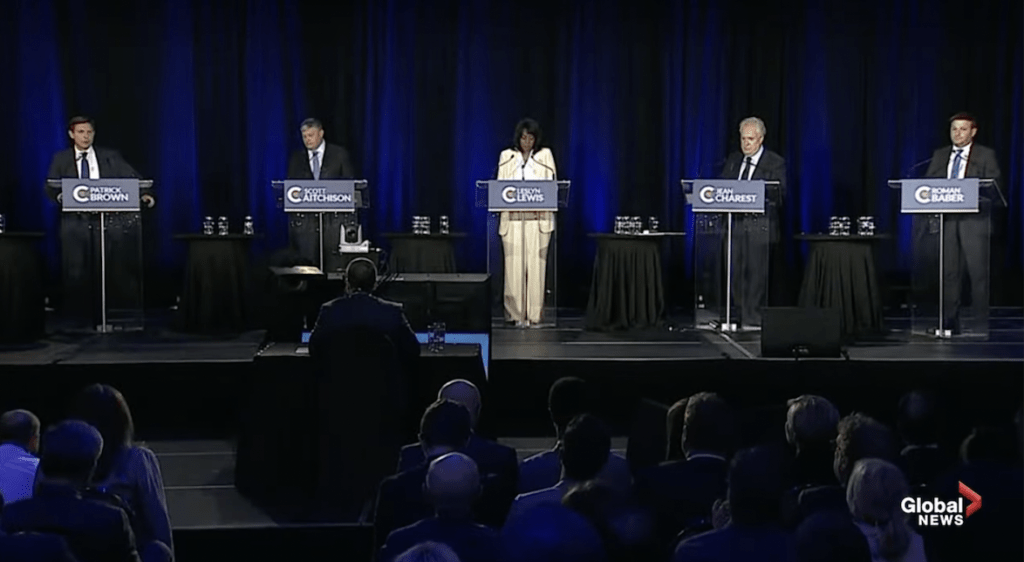

As has been evident in the first two (one unofficial, one official) English debates, right now, this is not so much about who will win as it is about what the party wants. Will it choose the Trumpian upstart, lizard brain-triggering, heat-seeking Pierre Poilievre, Canadian standard bearer of a very particular brand of politics, or — barring a surge by one of the other four candidates — the less obstreperous, Progressive Conservative Classic, former premier and turnkey leader Jean Charest.

Charest is a serious politician with serious experience who finds himself vying to lead an entity that may or may not be willing to follow him. Poilievre is a canny chancer peddling an assortment of emotionally charged keywords, some of which are attached to ideas, others to fears and still others to threats.

The contrast between these two men is exceptional not so much because of the difference in their ages (20 years), in their temperaments (reflexive belligerence vs. lawyerly logic), or in their rhetoric (hot emotion vs. cool persuasion) but because it can be hard to believe sometimes that they’re both competing to lead the same party. During fleeting moments of all three debates, Charest looked like a contestant who’d wandered onto the wrong Dating Game stage.

Is that because the post-Harper, post-Scheer, post-O’Toole Conservative Party of Canada bears absolutely no resemblance to the Progressive Conservative Party he led out of the wilderness into a protected political species management area in the 1990s? Is it because the loudest voices in the current Conservative base have a lock on the party so tight they’ve decided they’d rather lose federal elections indefinitely than water their Trumpian, blockader-BFFing wine? Is Poilievre ahead in the polls because he genuinely represents the current zeitgeist of the party and the math of that cannot be cracked within the existing organism? At some point, will the orphaned Red Tories still too Tory for the Liberal Party but too Red for this Conservative Party decamp to a new domain name closer in belief and branding to the moderate middle?

Watching the French debate as I write this, that’s the tension on display beneath the bouts of incoherent brawling, some of it in French dubbed “pénible” (painful) by Radio-Canada (except for Poilievre, who almost makes up for in fluency what he lacks in assonance, and Charest, who is bilingual/bicultural, accent-less in both languages). Charest is a serious politician with serious experience who finds himself vying to lead an entity that may or may not be willing to follow him. Poilievre is a canny chancer peddling an assortment of emotionally charged keywords, some of which are attached to ideas, others to fears and still others to threats. Which may be precisely what this Conservative Party of Canada wants.

This race seems less about revealing the candidates than about slowly defining a political party in transition through their comparative success or failure. While a lot can happen in four months, the result is more likely to hinge on where the party wants to go, and what it wants to be, than where anyone wants to take it.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington/international affairs columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.