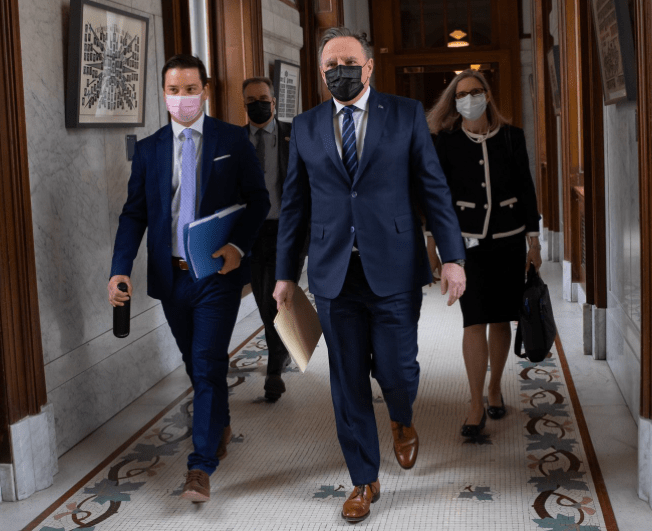

Legault’s Language Bill—A Third Way Between Sovereignists and Federalists

Stéphanie Chouinard

May 14, 2021

On Thursday, Simon Jolin-Barrette, Quebec’s minister responsible for the French language, tabled Bill 96, “An Act Respecting French, the Official and Common Language of Quebec”. This bill presented a much-awaited reform of the Charter of the French Language, one of the Coalition Avenir Québec’s (CAQ) electoral promises. While some changes surprise by their boldness, the majority of the proposed reform seeks to strike a compromise between protection for the French language and protection of civil liberties. What’s arguably most interesting about the bill, however, is the new vision it articulates for Quebec’s place in Canada.

Since Jolin-Barrette’s tabling of the bill, the single element of the reform that commanded the most attention has been the proposal of a unilateral constitutional change. It would see Quebec amend its constitution in order to recognize the province as a “nation” and to enshrine a disposition according to which “French is the only official language of Quebec [and] the common language of the Quebec nation.” This provision has already launched debate among constitutional experts in the media and will likely fuel even more energetic political argument.

Briefly, the first part of this proposal could most likely be adopted unilaterally by Québec, but the second may require federal approval. While this proposal may seem forceful, all provinces have access to these legal procedures through sections 43 and 45 of the Constitution Act, 1982. It is also not a decision without precedent. For example, in 1993, New Brunswick sought to amend the constitution in order to entrench dispositions of its provincial Act recognizing the equality of the two official linguistic communities. What remains unclear is whether support from Ottawa is necessary in order for French to be recognized as the sole official language in Quebec, and whether the federal government will be willing to do so.

Other important aspects of the bill seek the creation of a French-language commissioner and of a ministry of the French language, more powers for the Office Québécois de la langue française, and the recognition of a right to learn French and to work in French for all Quebecers. A new agency under the department of Immigration, “Francisation Québec”, will be responsible for overseeing all French-learning services. This measure clearly targets non-Francophone newcomers in order to give them more options for learning the province’s lingua franca.

Several other parts of the proposed reform seek not to enact sweeping changes, but rather to turn the dial a few degrees towards a stronger protection for French. For example, in the domain of exterior commercial signage – an issue that triggered an important controversy on the language of signs in the late 1980s, when then-premier Robert Bourassa invoked the notwithstanding clause to impose a French-only policy – minister Jolin-Barrette wishes to apply the rule of a “clear predominance” of French.

On the topic of local governance, out of the 97 municipalities with a bilingual status, those who have fallen below the threshold of 50 percent of English-speaking residents may now lose their status, unless their municipal council moves quickly with a resolution within 120 days in order to be grandfathered in.

With respect to access to English-language CÉGEPs, the CAQ had previously flirted with the idea of enacting the same rules it applies for admission into public Anglophone primary and secondary schools. The new regulations fall short of such a stringent policy, rather capping the proportion of students enrolled in the English-language college system at 17.5 percent and limiting the creation of new places to a maximum of 8.7 percent, while creating a standardized French test for all students who did not graduate from a provincial English high school.

As is often the case with compromises, this bill may seem reasonable to a majority of citizens, but those on both ends of the spectrum on the linguistic debate will be displeased.

A far more surprising aspect of the proposed bill concerns not Quebecers, but francophones outside Quebec. The preamble of the act endows Quebec with a special responsibility towards “la francophonie canadienne” with whom Quebec shares not only a language, but a history. Francophones will also now have access to the same postsecondary fees as Quebec residents if they enroll in a program in Quebec that’s not offered in their province of origin.

This apparent sign of largesse towards Francophone minorities was wisely designed not to compete directly with existing programs. It could nevertheless have detrimental effects for French-language and bilingual post-secondary institutions like Université de Moncton, whose main clientele is not only New Brunswick, but all of Atlantic Canada, or the University of Ottawa, which recruits students from francophone communities west of Ontario. It could even contribute to a “brain drain” of sorts for francophone communities, as the majority of students who leave their home province to study usually do not return home.

As is often the case with compromises, this bill may seem reasonable to a majority of citizens, but those on both ends of the spectrum on the linguistic debate will be displeased by this proposal. For Mouvement Québec français and the Parti Québécois, the new “half-measures” found in the bill are not going far enough to reinforce the status of French. Conversely, English-language organization Québec Community Groups Network reacted strongly against the bill, claiming it endangered some of its members’ rights, despite Premier Legault’s reassurances that the English-speaking minority would not be undermined by these proposals.

What is clear about this bill is that its aim was not simply to further the protection of French in Quebec, but also to send a message to the rest of Canada: Quebec will use what means the constitution gives it to affirm and elevate itself to the status of “nation within” and to protect its distinctive features, while remaining anchored to the Canadian federation.

Bill 96 possibly represents the most adroit embodiment of the CAQ’s autonomist “third way” politics, wedging itself between federalists and sovereignists, since the party came to power. The popularity of these proposals could spell trouble for an already embattled Parti Québécois, and leave little wiggle room for the Liberal Party, as they begin to lay the groundwork towards the next election.

Contributing Writer Stéphanie Chouinard is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Royal Military College in Kingston, cross appointed to Queen’s University. She specializes in language rights, Indigenous rights, federalism and judicial politics.