‘Knife’, a Love Story: The Tale Salman Rushdie Lived to Tell

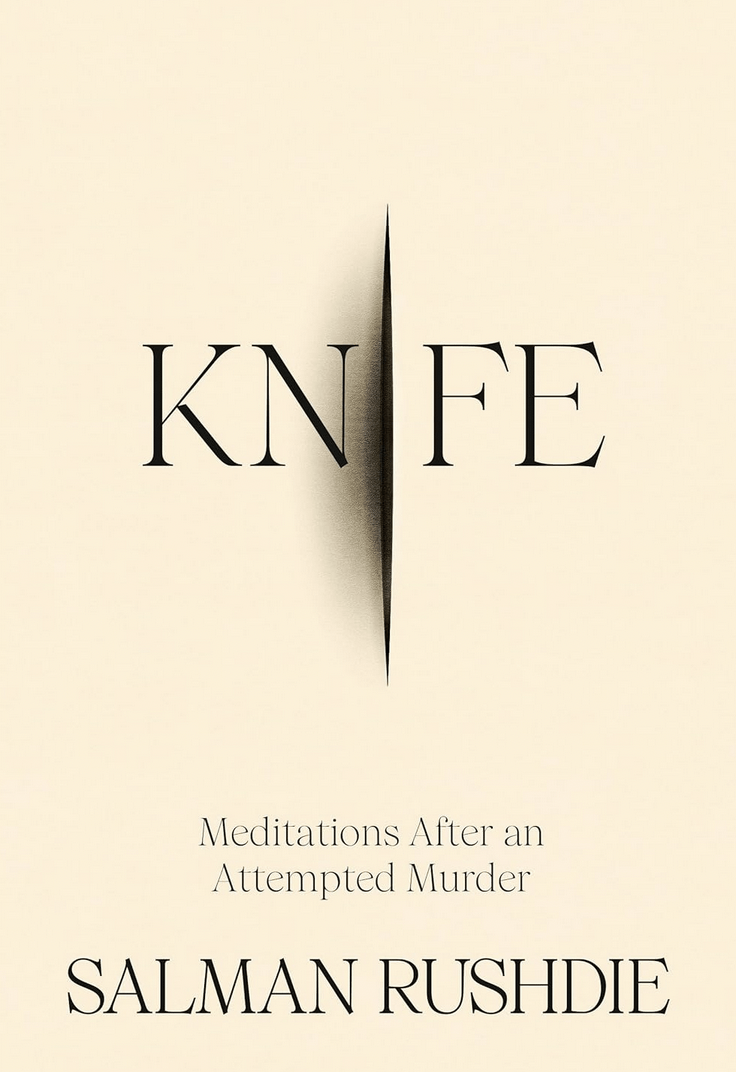

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder

By Salman Rushdie

Penguin Random House/April, 2024

Reviewed by Lisa Van Dusen

April 21, 2024

When the news broke on the afternoon of Friday, August 12th, 2022, that Salman Rushdie had been attacked by a knife-wielding assailant on a stage at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York, the question of whether he would live was more than a humanitarian, medical, legal or celebrity one.

What happened to Rushdie that afternoon was not just about a catalogue of injuries and the police-blotter details of a crime scene; the event would not be adequately addressed by a breaking wire story or a 3,000-word, third-person magazine article. The only thing worse than the brutality of the attack itself would have been Rushdie not surviving; leaving yet another deranged assassin with the last word on yet another American epic.

The real question was, would Rushdie live to write about it?

Like all epics, including the many Rushdie has written, this one is fraught with ironies and allegories, moral motifs and lessons both costly and priceless. In this epic, the writer is also the protagonist, having been hounded for decades by a tyrannical vendetta that finally catches up with him in broad daylight at a literary event.

“So, it’s you. Here you are,” Rushdie recalls thinking as the 24-year-old attacker he refers to throughout Knife, his new memoir of the attempted murder, only as A. — for a**hole, not attacker — comes charging toward him. Twenty-seven seconds later, Rushdie is lying in a pool of blood, having been stabbed 15 times before the assailant was tackled and subdued by the author’s interlocutor at the event, City of Asylum’s Henry Reese. By the end of it, among other injuries, the knife had taken Rushdie’s right eye and seriously damaged his left hand (now mostly functional again). He was there to discuss the protection of writers in dangerous times.

There followed hours of frantic emergency surgery at an Erie, Pennsylvania, trauma centre, days of uncertainty as to whether Rushdie would live or die, weeks of hospitalization, procedures, procedures and more procedures, and months of rehabilitation.

That Salman Rushdie was nearly killed by a fanatic fatwa late-adopter on a sunny day in a bucolic setting at a venue devoted, for the past 150 years, to “creative exploration, educational growth, relaxation and recreation” seemed, in real time, to be so fantastical as a biographical plot point that it smacked of the magical realism for which Rushdie is renowned — as if the diabolus ex-machina of a time-travelling ninja jinn had materialized out of thin air to hijack his story.

“Why now?” the author thought as he finally faced the savage absurdity of a hit job 33-and-a-half years after Ayatollah Khomeini put a bounty on his head based on the paranoia-torqued existential threat of words. “Really? It’s been so long? Why now, after all these years?”

Like all epics, including the many Rushdie has written, this one is fraught with ironies and allegories, moral motifs and lessons both costly and priceless.

So, this is not so much a crime story, though it is that. It is a much larger tale about freedom of speech, about a culture that has normalized disproportional retaliation of all kinds, and about an archaically analog attack in an age of violation defined by the sorts of incursions that generally don’t leave fingerprints: The extractive, destructive, privacy violations of wireless surveillance and hacking; the violations of norms we don’t know the value of until they’re gone; the violations of democracy committed through corruption and coercion to produce otherwise preposterous outcomes.

All violation — from harassment to stalking to assault to robbery to rape to murder to slavery to colonization to war — involves the obliteration of boundaries. The word violation, like the word violence, comes from the Old French violence (the French word for rape is viol), from the Latin violentia. Its word-association cloud includes force, breach, infringement, persecution, vehemence, suppression, imposition, outrage, injury, profanation, and, of course, power.

That day in Chautauqua, the violation Rushdie experienced was the most barbaric, old-school, rendition of cancel culture imaginable — an actual murder attempt — committed at the closest, boundary-obliterating range possible. “A gunshot is action at a distance, but a knife attack is a kind of intimacy,” he writes in Knife.

The author’s response to his particular violation has been to turn to love. Not, especially, love for his attacker, “a dumb clown who got lucky,” in Rushdie’s estimation, and whom he addresses in an imaginary conversation in Knife, but an appreciation of the love unleashed in response to the assault.

That includes the love of his wife, the poet Eliza Griffiths — not just the heady, romantic love of their courtship, but the harrow-hewn metamorphic love that got them through this nightmare. Also, the compassionate love that propelled the audience members who rushed to save his life and did. And, the love expressed by people around the world — from strangers on social media to presidents — who hoped and prayed for his recovery.

“One of the most important ways in which I have understood what happened to me, and the nature of the story I’m here to tell,” Rushdie writes, “is that it’s a story in which hatred — the knife as a metaphor of hate — is answered and finally overcome by love.”

Rushdie, who confesses to a post-traumatic Panglossian streak, has been chided for this passage — as though it’s a bit of too-trite exposition from a work of fiction rather than a revelation from a man who has survived the fulfillment, nearly mortal, of a three-decade existential threat.

At a time when so many violations are, at their most basic levels, defined by the weaponization of hatred, this is actually the timeliest, most valuable takeaway from Rushdie’s near-death experience. And given his status as an involuntary expert on the subject of weaponized hate, probably best to take his word for the likeliest antidote.

“I’ve always believed that love is a force. That in its most potent form, it can move mountains,” Salman Rushdie writes in the tale he lived to tell. “Love can change the world.”

Policy Magazine Editor and Publisher Lisa Van Dusen has served as a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington bureau chief for Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.