Kissinger on Canada, or Realism vs. Self-Righteousness at Madison Square Garden

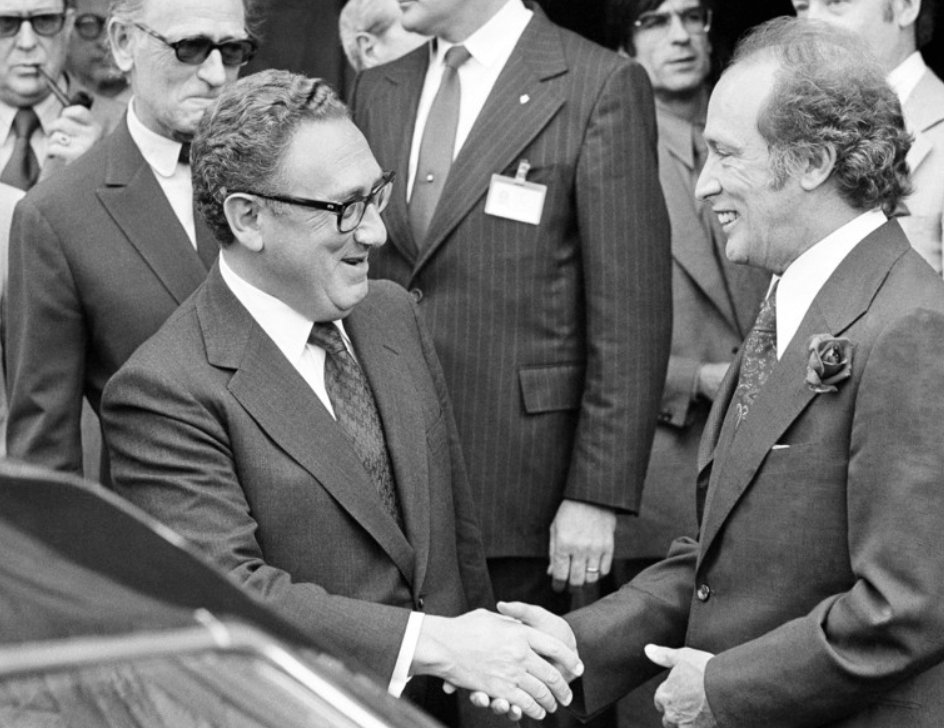

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, whom Kissinger praised for his role on China, in 1974/AP

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, whom Kissinger praised for his role on China, in 1974/AP

By Colin Robertson

December 3, 2023

“Canada…Canada… I have dealt with Canada since Vietnam. The word that comes to mind when I think of Canada is ‘self-righteous’. Yes, self-righteous. In Canada you get to do what is desirable. In America we must do what is necessary.”

I was nonplussed. This was not the response I had expected when I introduced myself — as having recently arrived at our Washington Embassy — to Henry Kissinger on that September evening in 2004.

We were at Madison Square Garden, scene of that election year’s Republican National Convention. The formidable former secretary of state had just given a rousing speech on national security to a group of Young Republicans. The friend who had gotten me into the session told me I looked “a bit stunned, but my grin — or was it a grimace? — was diplomatic”.

A decade later, I got a chance to respond.

This time, the setting was the comfortable confines of the 400-acre Greentree estate on Long Island, where the American Ditchley Foundation was hosting a conference on the US role in the world.

The conference was co-chaired by former Kennedy School dean and foreign policy sage Joe Nye and then-Brookings Institution President Strobe Talbott. Kissinger was the most prominent of a group of foreign policy experts that also included Jake Sullivan, now President Biden’s National Security Advisor.

I was rapporteur for the group looking at ‘soft power’, that variation on influence that we Canadians like to think we own, although today we do not invest sufficiently in either ‘soft’ or ‘hard power’. At the break, I re-introduced myself to Kissinger, recalling his words from our earlier exchange. That drew a smile from the man who left a massive footprint in 20th-century international affairs, including via introducing the term “shuttle diplomacy” into the popular vernacular. “That wasn’t very diplomatic of me,” Kissinger said. “You know, I have a lot of Canadian friends.”

He went on to reminisce about his meetings with Pierre Trudeau, saying the Canadian prime minister had made a ‘useful contribution’ to both North/South and East/West relations, and that Trudeau, who recognized China more than a year before Kissinger’s then-boss, Richard Nixon did, had also been helpful on that historic file. Kissinger then ventured that Canada can play a useful role as a bridge, “Or, how do you put it? — a helpful fixer — when you work at it.”

As his biographers have written, when Kissinger, who died on November 29th, wanted to charm, he could charm. I had admired Kissinger ever since reading A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-1822 (1957), his account of the 1815 Congress of Vienna, when I was an undergraduate.

Kissinger’s famous espousal of realism — the school of international-relations thinking based on the belief that states act in their self-interest and war is inevitable — drew on his ongoing study of history and his experience in dealing with the challenges of the Cold War. For the international system to function best, the realist argument holds, it requires the stability produced when anarchy is offset by the balance of power.

Having fled Germany as a teenager in 1938, Kissinger understood the perils of systemic disruption and the human cost of disorder. He read hisfellow German-Jewish intellectuals Leo Strauss, Hannah Arendt, and Hans Morgenthau, assimilating into his own thinking an appreciation of incrementalism, stability rather than justice, and the less bad rather than the unqualified good.

Even with the best of intentions and efforts, Kissinger was also aware of the ‘inevitability of tragedy’, the phrase Barry Gewen adopted for his The Inevitability of Tragedy: Henry Kissinger and His World (2020). Gewen argues that Kissinger recognized the “realities of power” and that his own “assessment of power” was clearheaded and un-swayed by “high moral principles like self-determination or national sovereignty.”

His diplomatic style was personal and secretive. It depended on relationships that could be developed only through personal contact. This meant being there again, and again and again. Diplomacy, like politics, is ultimately a retail sport.

As Kissinger frequently observed, peace is not the natural condition of humankind and democracy alone will not guarantee global peace and stability. Diplomacy is about the art of the possible. In the wake of the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kissinger would write “the test is not absolute satisfaction but balanced dissatisfaction.”These are the underlying premises of what came to be described as Kissingerian realpolitik.

Statecraft for Kissinger involved a close study of history and culture; a clear-eyed analysis of objectives aligned to a realistic appreciation of the possible; and personal relationships cultivated through continuous face-to-face contact, preferably on his opposite’s home turf. For Kissinger, the essentials of diplomacy were: “Knowledge of the history and psychology and psychology of the people I am dealing with. And some human rapport… To have some human relations with the people I am negotiating with…”

His diplomatic style was personal and secretive. It depended on relationships that could be developed only through personal contact. This meant being there again, and again and again. Diplomacy, like politics, is ultimately a retail sport.

The study of history and culture is critical and Kissinger’s erudite grasp of both permeates his own writing through 21 books and a half-century flow of commentaries and speeches.

Perhaps the best accounts of Kissinger’s diplomacy in practice are Margaret MacMillan’s Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World (2007) and Martin Indyk’s Master of the Game: Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy (2021). For MacMillan, Kissinger “showed an absolute aptitude for diplomacy and power…an incredible negotiator, a man of incredible stamina, and someone who was fully capable of matching up to Zhou Enlai in what were very difficult and very complicated negotiations.”

For Indyk, it was the “skillful manipulation of the antagonisms of competing forces.” In his appreciation of Kissinger following his death, Indyk wrote that the Kissinger approach – “to avoid bringing too much passion to the pursuit of peace” – continues to have relevance and application, notably to today’s Israel-Hamas war.

Opinion on Henry Kissinger’s legacy is deeply divided. One biographer, historian Niall Ferguson, labeled him an ‘Idealist’ (at least for the first and so-far only volume of his biography, which ends in 1968) while for Ben Rhodes, who served as Barack Obama’s deputy national security advisor, he was a ‘hypocrite’. The Washington Post calls him “One of the most consequential statesmen in US history”. To Rolling Stone, he was a war criminal for his culpability in the overthrow of Chile’s Salvador Allende and role in prosecuting the Vietnam War, yet Kissinger’s peacemaking efforts in Vietnam won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973.

Whichever side you come down on, Kissinger was a force for realism in internationalism with scant patience for those he regarded as poseurs or moralists. And it is important to understand Kissingerian realpolitik — a major theme of American foreign policy in the last half century and perhaps again in the future — as the United States debates and rethinks its role in the world.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.