Justin Trudeau faces the Sins of the Fathers in Indigenous Reconciliation Challenge

By Patrick Gossage

August 11, 2021

“The hurt and the trauma that you feel is Canada’s responsibility to bear, and the government will continue to provide Indigenous communities across the country with the funding and resources they need to bring these terrible wrongs to light. While we cannot bring back those who were lost, we can – and we will – tell the truth of these injustices, and we will forever honour their memory.” — Justin Trudeau on the deaths and unmarked graves of Indigenous children art former residential schools.

This was the tone of the Prime Minister’s reaction to the finding of over 700 unmarked graves of children at the site of a Saskatchewan residential school, and other continuing horrendous revelations. So many Canadians feel faced with damning evidence of the brutal way we treated the children of our native brothers and sisters that a recent Nanos Poll said 52 per cent of Canadians viewed reconciliation important to them in deciding how they would vote in a federal election. The question for the Prime Minister is not how more nice words of regret will play, but will there be any commitment to take real action to atone concretely for abuses Canada funded and tolerated for so long?

The sins of the fathers indeed, including Justin’s own. Pierre Trudeau’s failure to confront the way we treated our First Nations, Métis and Inuit must be shocking to his son Especially since he and his then-minister of Indian Affairs Jean Chrétien tried in 1969 to abolish the Indian Act severing the special legal relationship between First Nations and the government of Canada with the historic intent that Indigenous peoples be fully integrated into Canadian life. Happily, it failed but our Indigenous peoples don’t forget.

Surely the core issue to be addressed is granting First Nations greater self-determination. Justin Trudeau moves cautiously towards that central ambition of our Indigenous peoples. His lukewarm attitude is typified by his statement on National Indigenous History month: “We must continue to learn about and support the various existing governments, laws, and traditions that govern Indigenous nations to help Indigenous peoples build capacity to implement their vision of self-determination.” Hardly a ringing endorsement. Like many Liberals, I worry about the depth of the PM’s commitment to fundamental action and a true solution to endlessly festering indigenous issues.

Our Indigenous peoples have long memories and know full well where relations between “settlers” and their peoples came since the 18th century. It’s worth looking back over this story which is embedded in their culture. It is full of critical markers.

Until the late 18th century, the relationship between First Nations and the Crown was based on shared commercial and military interests. New France’s, then the early British colony’s economy had historically been based on the furs trade in which indigenous peoples played an essential role. Then the Indian Department had one primary goal—to maintain the peace between the small number of British soldiers and traders stationed at far-flung trading posts and the far more numerous and well-armed First Nations.

This mutually respectful relationship was formalized through commercial compacts and Peace and Friendship Treaties which did not provide Crown access to native lands. By 1763, there were growing concerns about settlers encroaching on First Nations territories. This was addressed in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This foundational document recognized the sovereignty of First Nations, their land rights, and their way of life. One observer wrote that it stated, “Any relations with Indigenous Peoples…, would be conducted on a nation-to-nation basis…The Indigenous Peoples would not be disturbed in their authorities and [in] the places that they called home for thousands of years, for hundreds of generations.” Current native leadership is well aware of this flagrantly disregarded precedent.

In the late 18th century, the Indian Department placed great value on strong military alliances with First Nations. They saw First Nations fighters as essential to the colony’s defence. During the War of 1812, First Nations fought alongside the British troops and Canadian colonists against the American invasion of the colony. As they did alongside Canadian troops in in the First and Second World Wars.

Good relations with Indigenous peoples were close and important to settlers as well. To survive, newcomers relied on their Indigenous partners’ skills and expert knowledge of transportation routes, food resources, and animals. Indigenous peoples do not forget that their ancestors helped early settlers, showed them how to sap trees, make clothing, learn to travel by canoe, use natural medicines, plant corn, and use snowshoes.

The current Liberals are indeed fighting the sins of the fathers. An official policy of assimilation started to show its ugly face in the early 19th century. In Upper Canada, First Nations were simply getting in the way of rapidly spreading agricultural and industrial growth. British administrators began to regard First Nations as dependents, rather than allies. A new perspective was emerging throughout the British Empire about the role the British should play regarding Indigenous peoples. It was based on the belief that British society and culture were superior; there was also a missionary fervour to force British “civilization” on Indigenous peoples.

In the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada, the Indian Department became the vehicle for this new strategy. In 1839, the Crown Lands Protection Act, made the government the guardian of all Crown lands, including Indian Reserve lands. Then in 1857 the legislature passed the Gradual Civilization Act which started to treat Indigenous peoples as wards of the state with the objective of absorbing them into European settler society. Then in 1860 Britain transferred jurisdiction over Indigenous peoples to the colonial administration – in effect to land- hungry settlers. The key piece of post Confederation legislation further entrenched control of the lives of Indigenous peoples. The Indian Act of 1876 gave greater authority to the Department of Indian Affairs to intervene in a wide variety of internal band issues and make sweeping policy decisions, including who was an Indian. The Department would manage Indian lands, resources, and moneys; and promote “civilization.” It effectively transferred the self-government they had enjoyed for thousands of years to the Canadian state. In the pursuit of more effective assimilation, it then set up the residential school system in the 1880’s.

Justin Trudeau has made many grand promises to restore rights to First Nations and restore a true nation-to-nation relationship. He stood in the House of Commons in 2018 promising a recognition of Indigenous rights framework that would get rid of the Indian Act. Trudeau made another lofty promise: having the legislation written by the end of 2018, only to see if fall apart later that year.

His powerful Indigenous Minister of Justice Jody Wilson-Raybould was a thorn in his side on this issue and said in 2020: “I know what Indigenous people have been asking for generations and that is to have true recognition of their rights … it’s beyond dispute; Indigenous people have the right to self-government to self-determine how their nations and their communities move forward,” She fought with Carolyn Bennett, now Minster of Crown Indigenous Relations, over implementation of such a move but the plan was dropped as the SNC-Lavalin scandal broke and Wilson-Raybould was expelled from cabinet and then from caucus. We have not heard the last from this most credible spokesperson for Indigenous peoples Nations. She is writing what will be a revealing book on her time as the “Indian” in Cabinet and how her views were largely ignored. It could be a problem for Trudeau if it appears during an election.

While the framework legislation wasn’t tabled, its influence was seen in bills, such as C-92, the Indigenous Child Welfare Act and C-91, the Indigenous Languages Act, both of which were tabled and passed in last couple of months of the previous term.

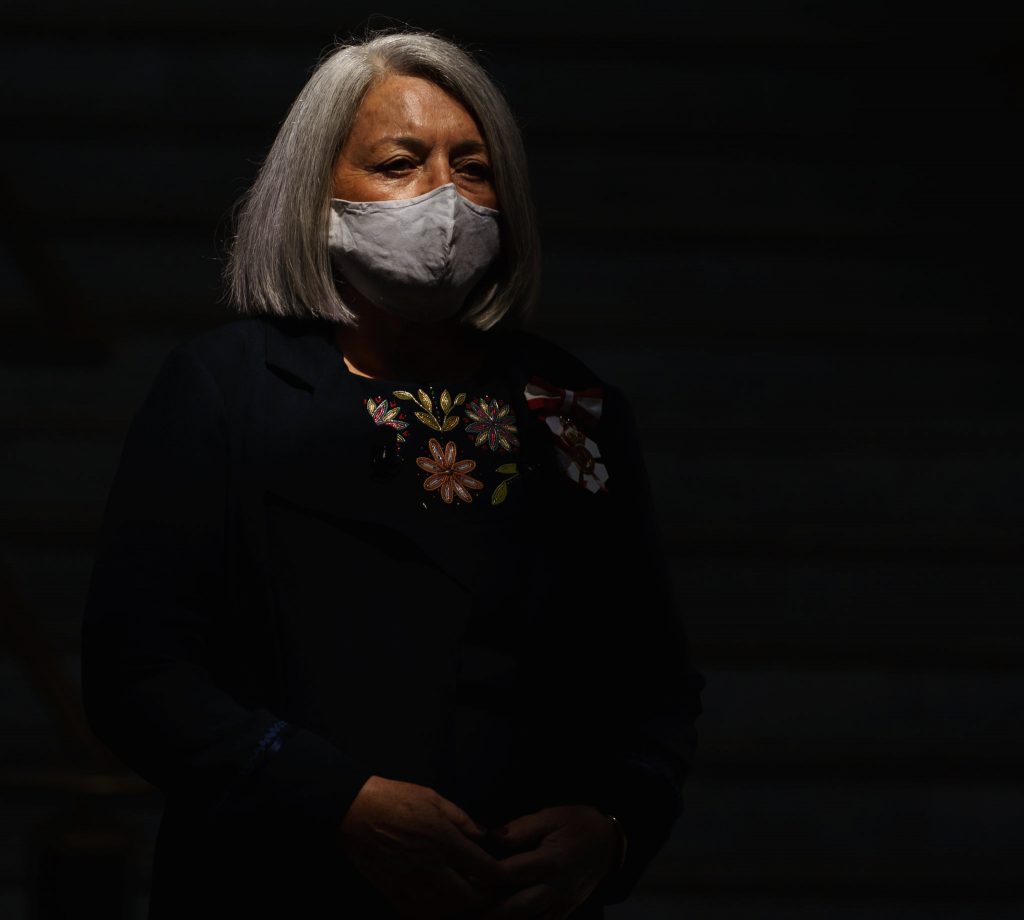

The government’s recent granting of authority over child welfare to the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan where over 700 unmarked graves of children were found just days before the announcement, shows a slow, piecemeal approach to expanding rights. The impressive record of the new governor general, Mary Simon, in lobbying for Inuit rights could surely weigh into a more activist government approach on this broader issue.

Her appointment as Canada’s first Indigenous governor general, in the wake of the national reckoning over residential schools, comes at a propitious moment, and Trudeau deserves full credit for seizing the opportunity. Her investiture was an impressive ceremony, especially remarkable for the presence and performance of Indigenous activists and artists. And her first address as GG was equally striking for her sense of occasion, in speaking her native Inuktitut as well as English, and pledging to learn French, to generally approving comments from French-language media.

A larger recognition framework is unlikely to be a platform piece in a federal election. It has not been presented in a way that galvanizes the public even if reconciliation is recognized as a desirable goal. The amplification of the genocide positioning and call for independent judicial inquiry to attach blame and responsibility for this “genocide” may heat up the missing children issue politically. As may the Catholic church’s continuing reluctance to accept responsibility or come to the table with appropriate restitution funds.

Don’t look to the Conservatives to push the government. The recent Senate passage of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which was voted against by the Conservatives in the House since it calls for free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) from Indigenous peoples on anything that infringes on their lands or rights. It also foresees Indigenous self-government.

Will the Trudeau Liberals champion the granting of Indigenous peoples further rights in an election? Can this be the much sought-after final step to true reconciliation, the ceding of the federal government’s paternalistic role in directing Indigenous affairs, while sustaining generous financial support for isolated communities?

History is indeed catching up on us. Our collective consciousness might just be ready for a radical revamp of the relationship and a more generous act of concrete reconciliation. Does the Liberal government have the guts to finally do the right thing for our original inhabitants? I have some faith in the growing will of Canadians to support a government that faces up to its responsibility to drastically remake the relationship. What better legacy for Justin Trudeau? Otherwise, what Numbers says in the Bible will remain true: “The Lord visits the iniquity of the fathers upon the sons to the third and fourth generation.” At least.

Contributing Writer Patrick Gossage, former Press Secretary to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau from1979-83, is the author of Close to the Charisma: My Years Between the Press and Pierre Elliott Trudeau. He is the founder of Media Profile, a public affairs firm based in Toronto.