Job One for A New Leader—Putting the Party Back Together

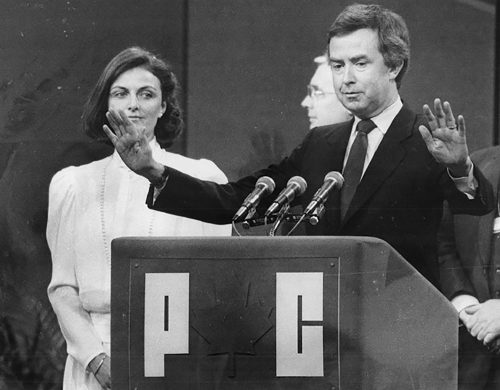

If there’s a best practices model for managing the bruised egos, loyalty rewards and score-settling reflexes of a post-leadership Conservative Party, it is arguably the victory of Brian Mulroney over Joe Clark in 1983. Veteran Tory strategist and Earnscliffe Principal Geoff Norquay, who survived that transition and thrived through subsequent leadership changes, provides a blueprint for keeping the party together.

Geoff Norquay

Erin O’Toole is the newly crowned leader of the Conservative Party and leader of the Official Opposition. Like all new leaders, he faces a huge set of challenges and opportunities, complicated by a minority government weakened by scandal and the country still in the throes of a pandemic. But before he turns his mind to those issues, he must ensure a clean launch by healing the wounds of the leadership contest and putting the party back together. Doing so effectively requires all the leadership skills—sensitivity, decisiveness, patience, generosity, balance and team building.

The stakes are high for a successful transition: issues from leadership campaigns that are not put to rest have a habit of returning and hurting the leader and party later on.

Leadership contests are risky times for political parties. Caucus members are forced to pick sides. Longstanding personal friendships can be made or destroyed. Harsh words are spoken, and dirty tricks played. Policy, ideological and regional cleavages can emerge and grow. Serious and lasting damage can be done to a party if the new leader does not act quickly and effectively once it is all over to heal the wounds left by a leadership race.

When election day comes and a new leader is crowned, the contenders gather onstage, the losers pledge their fealty to the winner and their collective intention to march forward arm-in- arm toward a brighter future. That’s when the new leader faces his or her first big challenge—putting the party back together.

That’s usually the way when the convention is live in one hall. The end of the Conservative leadership race on August 23 was a reflection of the times—a virtual event in deference to the pandemic, with the results of ranked ballots simply announced by party officials. But live audience or not, the immediate challenge for a new leader remains as always—unite the party. Period.

How a new leader sets about transition and its success are critical to the party’s and his or her future fortunes. There’s no available handbook to consult; each new leader and team must create a plan and get to work. The smart ones will have anticipated the win and put in place a rudimentary transition plan. If the party is currently in office, obviously that planning step is both essential and critical: there’s a government to be made over and a country to run.

The first overtures the new leader must make are to the other contestants in the race. This is the first critical step in forming a new and cohesive team. On both sides—the winner and the losers—any lingering animus from the campaign must be set aside, and sensitivity shown for any bruised feelings about what might have been. An exchange of views on potential future roles is the starting point and may involve an offer of the deputy leader’s position, a preferred cabinet or senior critic role, or even some time off to recharge batteries.

After he lost the Progressive Conservative Party leadership to Brian Mulroney in 1983, Joe Clark chose to step away from day-to-day politics for a few months and became a visiting professor at York University in Toronto. Mulroney wisely gave Clark the room for reflection and recovery, and he was soon back to vigorously fight the 1984 election. Afterwards, when he rose for the first time in the House as the newly appointed Minister of External Affairs, his first words—delivered with a broad smile—were, “As I was saying before I was so rudely interrupted….” It was a pretty good recovery from what had been a shattering defeat.

Relations between the two top contenders after a leadership do not always go as smoothly. When Tommy Douglas beat Hazen Argue for the leadership at the founding convention of the NDP in 1961, Argue became a Liberal, later a Liberal Senator. For the rest of his life, locals would cross the street in Saskatoon rather than greet him. After attempting to split the party with the “Waffle,” Jim Laxer challenged David Lewis for the leadership in 1971. Many in the party considered it such an offensive insult that they never spoke to him again.

At the Liberal Party leadership debate in Montreal in 1990 when Jean Chrétien refused Paul Martin’s challenge to endorse the Meech Lake Accord, hundreds of Martin youth supporters chanted “vendu” (sellout) and “Judas” at Chrétien, who blamed Martin and never forgot the slight. Martin served as a highly successful finance minister for nine years under Chrétien, until Martin’s acolytes ultimately pushed too loudly for the prime minister to leave, and Chrétien fired him from cabinet. The discord resulting from that Shakespearean power struggle—mirrored in the Tony Blair-Gordon Brown internecine Labour battles in the UK with similar outcomes—split the Liberal Party for well over a decade.

The second set of essential discussions for the new leader is with his or her strongest supporters in caucus and in the party. The key point to make is that this is not a time for triumphalism or hot talk about the settling of scores from the leadership. The message needs to be, “OK, we won, but now I need to bind up the wounds in the party, so I need you to be quiet while I do that.” That’s the approach Brian Mulroney took in the wake of his leadership victory in 1983; it calmed everyone down after a bruising contest and sent the message that there would be no retributions based on who had supported whom.

The new leader also faces potentially difficult decisions about how to staff the leader’s office and party headquarters. The people who have just worked so effectively to elect you leader may not be the right ones to run your office or a federal campaign and some may have to be let down easily. In addition, key supporters of other leadership contenders may have distinguished themselves as skillful managers, communications professionals or policy advisors, and they may deserve a key position. Such a move will help smooth relations with defeated rivals.

Next, what is the new leader to do with the leader’s office staff he or she has just inherited? Some top advisors to the outgoing leader will obviously depart, but what about the rest: who should leave and who should stay? When Mulroney became leader of the PCs in 1983, I was Clark’s director of research. The day after his victory, the Toronto Star identified me as the second on a list of three or four senior staffers likely to be “dropped head-first off the Peace Tower.” I survived the transition because members of caucus told the new leader’s advisors that my research team had been particularly attentive to serving them in a difficult period over the three previous years. When Mulroney won in 1984, Hill and party staff moved smoothly into PMO and ministers’ offices.

Mulroney was magnanimous with others too. Peter Harder had been Clark’s principal secretary and was now out of a job as a result of the leadership change. The new leader helped Harder with a move to a position in a Crown corporation. Harder quickly returned to Ottawa within a year, served as Chief of Staff to Erik Nielsen, the deputy prime minister, and ultimately went on to a stellar public service career as the deputy minister of several major departments in the governments of Jean Chrétien and Stephen Harper.

When Justin Trudeau moved into government in 2015, he and his senior advisors went out of their way to make a clean break with the past. They studiously avoided bringing in battle tested staffers from the Martin and Chrétien eras to PMO and ministers’ offices. The result was that in its early days, the new government lacked exempt staff with the necessary institutional knowledge of how the federal government worked, which created problems both internally for lack of experience and externally as the veterans left out became a chorus of unattributed critics.

Leadership races can bring out the worst in parties, but they can also bring out the best, such as the testing of ground-breaking organizational techniques or innovative policy, communications or fundraising approaches. Leaderships are also often a valuable recruitment tool for parties as they bring in new people eager to road-test new approaches and ideas. That’s the way the “Big Blue Machine” (BBM) rose to prominence in 1971 through the election of Bill Davis as the leader of the Ontario PCs.

According to all expectations, Davis should have walked away with the 1971 leadership contest to succeed John Robarts. Only 41, and with nine years as a highly successful Minister of Education and University Affairs, he was the logical successor. On a snowy night at Maple Leaf Gardens at the end of an old-style delegated convention, Davis eventually emerged victorious, but the final result was a squeaker, with a razor-thin 44-vote plurality over cabinet colleague Allan Lawrence.

The principals behind the BBM, Dalton Camp and Norman Atkins, were well-known to Davis and the PCs (they were behind Robert Stanfield’s federal leadership victory in 1967), but Davis was wary about Camp’s very public campaign against the leadership of John Diefenbaker and believed their support would be toxic. As a result, they supported Lawrence, and almost defeated Davis.

Immediately following the leadership, Davis brought Camp and Atkins onside and the rest was history. The Big Blue Machine became the campaign organization that dominated Ontario and national politics for a generation, playing a key role in the election of Mulroney in 1984 and becoming the brains trust of “go-to” strategists for many conservative politicians across Canada and in several other countries. Its generations of alumnae—among them Toronto Mayor John Tory—still occupy positions of influence across Canada.

The final set of transition decisions facing a new leader is to form the shadow cabinet. In addition to reflecting gender and regional balances and taking aptitudes, experience and expertise of caucus members into account, the leader needs to seek balance between his or her supporters and those of other candidates. These appointments will be watched closely within the party for favouritism.

In 2004, following the creation of the new Conservative Party from the former Reform Alliance and Progressive Conservatives, newly elected leader Stephen Harper faced a difficult set of choices in creating his shadow cabinet. Within the new party’s merged caucus, he had to move high profile Reform Alliance critics out of their positions to make way for the incoming PC MPs. This was achieved with significant sensitivity on the leader’s part and generosity on the part of those who were making way for the newcomers. Many people put water in their wine to make a bold experiment work.

Like everyone else in a new job, new leaders never get a second chance to make a first impression. Canadians will be watching how the new Conservative leader handles his first big challenge.

Contributing Writer Geoff Norquay, a Principal of the Earnscliffe Strategy Group in Ottawa, was research director for Conservative Leader Joe Clark, senior adviser on social policy to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and later was Director of Communications in opposition under Stephen Harper.