Jimmy Breslin: Not an Enemy of the People

Lisa Van Dusen/For the Hill Times

March 22, 2017

I was reminded Sunday of an applause line Joe Biden used during the 2012 presidential campaign to sum up the state of America: “Osama bin Laden is dead and General Motors is alive.” Pondering the news coming across my Twitter feed, it seemed the line required updating. “Jimmy Breslin is dead and Donald Trump is president.”

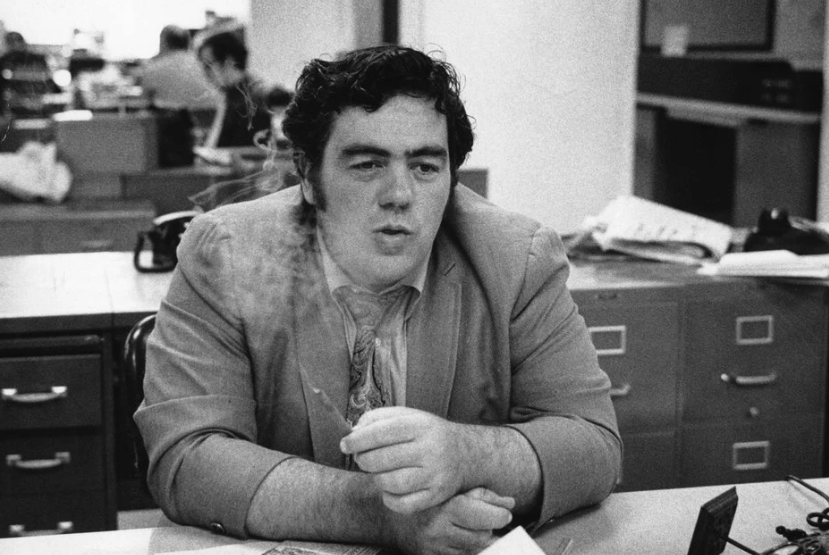

For reporters of not just a certain generation but of a few of them, Jimmy Breslin embodied the romance of the profession the way Woodward and Bernstein represented the craft. The journalists who knew and worked with Breslin, some legends in their own right, have eulogized the larger-than-life character; the cigar-chomping curmudgeon with a heart of gold, a nose for bullshit and an unfailing respect for the human beings who weathered unprotected the consequences of decisions made in offices they’d never see but whose occupants read Jimmy Breslin.

For those of us who grew up outside of America, he represented that, too, particularly New York. Jimmy Breslin was living, barking proof that New York was a place where a reporter could be a smartass and maybe even a pain in the ass and, as long as they did the job well, not end up on Riker’s Island or as a binding agent in a divider on the New Jersey Turnpike. Speaking truth not so much to power as about power was a role that was not just tolerated but valued. There were many reasons to fall in love with New York and Jimmy Breslin was one of them.

So, it seems only fitting that Breslin should die at a moment in America’s story when the president of the United States has called journalists enemies of the people. Of all the stupefying things Donald Trump has said, associating that label with what Jimmy Breslin did for a living seems especially egregious.

At what, at least so far, still stands as America’s darkest post-war moment, Breslin had the heart to drift away from the herd and talk to Clifton Pollard, who was performing the historic task of digging John F. Kennedy’s grave after he was murdered by a real enemy of the people. He wrote about the death of Eduardo Gutierrez, an 18-year-old illegal immigrant accidentally and avoidably killed on a construction site in 1999, then wrote a book about it. He wrote the story of David Camacho, a gay man losing both his life as he knew it and his physical life to AIDS in 1985, humanizing the acronym at a time when the stigma around the disease was still so potent that it would be another five years before Princess Diana would make worldwide news by shaking the hand of an AIDS patient.

He dignified the pain of the powerless and wrote history through the eyes of its victims instead of chronicling the glory of its architects. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1986 for, in the words of the Pulitzer board citation, “columns which consistently champion ordinary citizens.”

Jimmy Breslin was not an “enemy of the people.”

Not all journalists are Jimmy Breslin and journalism, like so many of the crucial components of democracy, isn’t what it used to be. But there are two other words that came to mind when I was reading his obituaries: “witness” and “truth.”

Reporters bear witness and provide society with a baseline of truth, whether you try to undermine that role by branding it “fake news” or not. Those are both functions worth protecting, especially at a time when they also seem to be worth attacking.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.