James A. Baker III: Iron Fist in a Velvet Glove

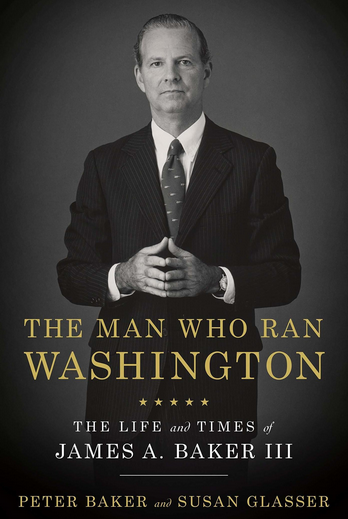

The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III

Doubleday/Penguin Random House, September 2020

By Peter Baker and Susan Glasser

Reviewed by Derek H. Burney

October 9, 2020

Based on a seven-year marathon of prodigious research and interviews, New York Times columnist Peter Baker (no relation to the subject) and his spouse, Susan Glasser of the New Yorker, have compiled a long overdue biography of James A. Baker – The Man Who Ran Washington – that is rich in insights and lessons about how the “indispensable man” made government in Washington work.

Baker set the gold standard for what was then viewed by insiders as the second most-powerful job in Washington when he served as Ronald Reagan’s first chief of staff, establishing order in what was initially a chaotic White House and focus and discipline across the administration. He cleverly sidelined or outfoxed internal rivals and rapidly became the go-to man in Washington. Later, as secretary of treasury in 1986, he smoothly stick-handled major tax reform through a Democrat-controlled Congress.

As secretary of state, Baker and president George H.W. Bush “managed the most tumultuous period in international politics since World War II,” leading the western alliance peacefully and cohesively through the cataclysmic events of the early 1990s – the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the unification of Germany. They also gained unique support from the United Nations to drive Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait with a multinational coalition that included Canada.

Baker and Bush Sr. were very close friends, but also competitors, a friendly rivalry nurtured through years of spirited tennis matches. When they differed, Bush was known to quip “If you’re so smart, how come you’re not the president?”

Even though Baker seemed to operate discreetly in the background, he systematically burnished his own image with selective leaks to trusted friends in the media. In Washington, that is often key to success and survival. “He was calculating and cunning and opportunistic in all the ways that reflected the city whose top jobs he conquered one by one.”

As meticulous in appearance as he was in preparation, Baker believed that “the point of holding power is to get things done,” a view that was the “currency of the realm in the Washington of Baker’s era.” His strong suit was deal-making. He also had a knack to recruit top-flight, highly talented and steadfastly loyal lieutenants to support his objectives. He knew how to get results domestically and globally, which is no doubt why Obama’s national security advisor, Tom Donilon, described him as “the most important unelected (American) official since WWII.” He ran Washington when Washington still ran the world.

While his career was not without high-stakes drama, Baker’s personal life had the makings of a book all its own. In 1973, three years after his beloved first wife, Mary Stuart, died of cancer, Baker and her best friend, Susan, married. The scene of Susan letting Jim Baker know where his late wife had left a parting letter for him, the details of that letter, and the partnership Jim and Susan Baker forged in the decades since — having added a daughter of their own to his four children and her three — help to humanize a man known more for his head than his heart. (While James and Susan Baker tested positive for COVID-19 in August, both are reportedly recovering well).

As meticulous in appearance as he was in preparation, Baker believed that “the point of holding power is to get things done,” a view that was the “currency of the realm in the Washington of Baker’s era.”

I had two memorable engagements with Jim Baker. When he was designated by President Reagan to try to salvage the free trade negotiations that had been suspended in September 1987, I was given the same responsibility by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. Along with our respective teams, we negotiated intensely over three days in Washington just before the administration’s fast-track authority to conclude the trade negotiation was due to expire at midnight, October 3rd. We began by isolating issues on which there was general agreement, so that we could concentrate on bridging gaps and outstanding differences. At one point, when I explained carefully why Canada needed an exemption for culture, Baker interjected in his inimitable Texan twang “Derek, in Texas we call shugah (sugar) cultcha (culture)!”

The sticking point for Canada was a binding dispute settlement mechanism. We had signaled firmly that we would not conclude an agreement without it. Ultimately, and literally at the eleventh hour, and after receiving a direct phone call from Prime Minister Mulroney, Baker burst into the small office next to his at Treasury where the core Canadian group was assembled. He flung a piece of paper at me and, as the authors recount, declared “There is your goddamn dispute settlement mechanism. Now can I send our report to Congress?” After quickly scanning his terse note, we gave it a thumbs up. We learned later that Baker had to crack heads on his legal team to get concurrence. They were afraid it might be unconstitutional. He had also taken direct soundings with key Democratic leaders in Congress to ensure their support.

In his own memoir, Baker described the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement as a “Near-run thing.” It definitely was that. He also said it was one of two major economic achievements by the Reagan government — the other being tax reform. Neither would have happened without his tenacious commitment to deliver what his president wanted.

Over and above the substantial, bilateral benefits – trade tripled during the first ten years – the FTA became a template for other free trade agreements. It also prompted conclusion of the Uruguay Round of Multilateral trade negotiations – the last of its kind to succeed.

The second engagement came when I served as Ambassador in Washington from 1989-93 and Baker was secretary of state. The Bush administration had announced that it intended to negotiate a free trade agreement with Mexico. Alarm bells rang in Ottawa given the threat this could pose to the preferential status we had just established with the United States. Despite some free trade fatigue in Ottawa, including around the cabinet table, I was instructed to request formally that Canada be included in what became NAFTA. I did so directly with Baker, invoking the close personal ties between President Bush and Prime Minister Mulroney. I pressed our case even more vigorously with his top economic official, Bob Zoellick.

Much later, we learned that some in the administration, notably US Trade Representative Carla Hills, were adamantly opposed. They were concerned that Canada would delay and complicate their real objective with Mexico by re-opening old disputes. I assured Baker emphatically that our motive was to preserve and, if possible, improve what had been negotiated, not frustrate a successful outcome. Ultimately and not surprisingly, President Bush and Secretary Baker carried the day. (Despite Donald Trump’s persistent castigation of NAFTA as the “worst trade deal ever,” the USMCA retains most of its key elements, including and notably the dispute settlement mechanism).

On both occasions, I witnessed firsthand the steely resolve of Washington’s “Mr. Fixit,” whose ability to negotiate shrewdly had few parallels. He had a spine of steel and could be ruthless when necessary, an essential element for those at the highest echelon of power in Washington and one reason why I, among other Canadians, described him (affectionately) as “the iron fist in a velvet glove.”

Baker’s reputation has grown deservedly over time because he excelled at the type of bipartisan deal-making with Congress, with the Soviet Union and other countries that no longer seems possible. Using a pragmatic rudder while carefully nurturing political opponents at home and assuaging often prickly alliance personalities, he left a distinctly positive imprint on policy and strategy when America was at the top of its game.

The Baker-Glasser book chronicles how Baker used networking, tactical prowess, a streak of crafty, determined negotiating skills and a little luck to advance American interests. The unique skills of Jim Baker were essential in delivering great things for America and for two very different Presidents.

It is a riveting and, at times, moving read.

Policy magazine contributing writer Derek H. Burney was chief of staff to Prime Minister Brian Mulroney during the negotiation of the Canada-U.S. Free Tree Agreement in 1987, and Canadian ambassador to the United States during the NAFTA negotiations of 1991-92.