Is Fiscal Responsibility an Issue in the 2019 Campaign?

It isn’t often that a fiscal policy announcement upends the trajectory of an election campaign narrative, but that’s what Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau’s pledge on deficit spending did in 2015. In four federal budgets since then, Finance Minister Bill Morneau has displayed none of the previous government’s fixation on balanced budgets and the results have been generally positive, writes former Parliamentary Budget Officer Kevin Page.

Kevin Page

With the federal election underway, it’s safe to say all parties are busy costing their campaign promises, and those of their opponents, too. This tradition is strengthened this year as the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) has been given resources to help parties cost individual measures. When we add up all the individual measures costed by the PBO, how will political parties plan to pay the bill—will they raise taxes or increase the public debt?

Will fiscal responsibility be front and centre in the election? Have modest budgetary deficits become the new normal? Is it time for a reset of fiscal policy?

If we wind the clock back to the 2015 campaign, a case can be made that fiscal policy played a role in the debate and maybe the election outcome. As you may recall, the Conservative government’s fiscal strategy was a balanced budget approach largely laid out in Budget 2015. At the time, many observers argued that given the weakness in the economy—year over year growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) fell to zero—this fiscal strategy likely hurt economic growth, at least in the short run. Going into the campaign, the NDP, then the Official Opposition, had argued for a balanced budget over the medium term, but proposed tax increases for the corporate sector to help finance expansion of social programs. While a case could be made that what the NDP proposed was responsible (sometimes referred to by policy wonks as a balanced budget multiplier as taught by the late Paul Samuelson), some observers were surprised that the NDP would recommend a balanced budget track like the Conservatives, given the weakness in the economy.

In a move that shook up the campaign, the Liberals, the third party at the time, made the case for deficit-financed spending on a range of public policy issues including infrastructure and child benefit programs. This approach stood out both politically for staking out the NDP’s traditional terrain on the left and leveraging the Conservatives’ fiscal immobility on the right and policy-wise at a time when austerity had acquired quite a bad name elsewhere in the world. It was an approach that had the support of the International Monetary Fund as well as some leading economic thinkers of our time including former Bank of Canada governor David Dodge in Canada and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers in the United States. Given the low interest rates, why not borrow money to address public policy shortfalls including a perceived infrastructure deficit? The Liberal strategy was widely considered to have played a part in the party’s decisive majority.

Credibility of fiscal plans depends on a number of factors. The economic environment—fiscal policy (like monetary policy) can have an important impact (positive or negative) on the growth of the economy. The fiscal balance sheet—the ability of governments to finance new proposals—will depend on fiscal room to maneuver linked to a number of factors, including the budgetary balance, size of debt, and the carrying cost of public debt interest.

Scott Clark—a past deputy minister of Finance in Canada—has made the case that the bottom lines of fiscal responsibility are about establishing and maintaining a sustainable medium-term (next five years) and longer-term fiscal framework. It involves developing a fiscal strategy and plan that allow governments to address public policy issues without creating imbalances that lead to unsustainable debt burdens that constrain the policy choices of future governments and generations.

By those measures, the case can be made that the fiscal policy of the Liberal government over the past four years has been responsible. It kept federal budgetary deficits to a relatively low percentage of GDP—less than one percentage point per year. In an environment of relatively low interest rates (i.e., the so-called negative interest and growth rate environment created following the 2008 financial crash whereby effective interest rates are lower than the nominal GDP growth rate), this level of budgetary deficits is deemed sustainable over the medium term.

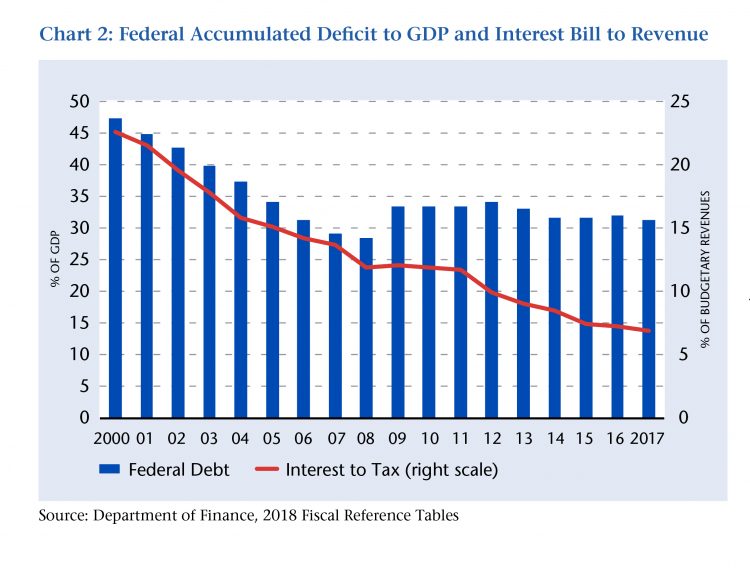

While the accumulative deficit increased by $57 billion from 2014-15 to an estimated $686 billion in 2018-19, as a percent of GDP this level of debt is relatively low by domestic and international standards and only modestly above recent historical lows established before the 2008 crisis. Notwithstanding the increase in public debt, the carrying cost of public debt interest (gross public debt interest charges as a percent of budgetary revenues) has actually fallen to historical lows because of the decline in effective interest rates (see Chart 1). Furthermore, and very importantly, analysis by Finance, PBO and the IMF suggests that the federal fiscal structure is sustainable over the long term in the face of aging demographics (by contrast, with the exception of Quebec, provincial governments are not fiscally sustainable).

Is it nonetheless possible to critique the Liberal government for shortfalls in fiscal policy?

Absolutely. In their 2015 election platform, the Liberals promised a balanced budget over the medium term. This target was within reach in 2018-19 as the economy strengthened in 2016 and 2017 and as revenues exceeded expectations on the backs of a strong labour market. They chose to spend the fiscal dividend. So, while the Liberals may have been responsible they were not accountable.

The current deficit is deemed to be structural in nature as calculated by the Department of Finance (2018 Fiscal Reference Tables). This raises the policy question, largely unanswered by the Liberals, of why run budgetary deficits when the economy is operating at a healthy trend? Do we need pro-cyclical fiscal policy to promote growth if the unemployment rate is at recent historic lows—below 6 per cent? While international organizations like the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have applauded Liberal government efforts to make policies more inclusive—increased spending on child benefits, Indigenous child welfare, public infrastructure—it is more of an open question as to whether this spending has been efficient and effective. Clearly, the project management and spending related to the disastrous pay system inherited from the Harper government—the Phoenix system is three times over budget with critical operational failures—was not responsible fiscal management.

The current deficit is deemed to be structural in nature as calculated by the Department of Finance (2018 Fiscal Reference Tables). This raises the policy question, largely unanswered by the Liberals, of why run budgetary deficits when the economy is operating at a healthy trend? Do we need pro-cyclical fiscal policy to promote growth if the unemployment rate is at recent historic lows—below 6 per cent? While international organizations like the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have applauded Liberal government efforts to make policies more inclusive—increased spending on child benefits, Indigenous child welfare, public infrastructure—it is more of an open question as to whether this spending has been efficient and effective. Clearly, the project management and spending related to the disastrous pay system inherited from the Harper government—the Phoenix system is three times over budget with critical operational failures—was not responsible fiscal management.

The economic winds are now blowing in a different direction and the clouds on the horizon are looking darker. The bond markets and a number of economic commentators (including Summers) are raising concerns about a possible recession over the short term. International organizations are calling for some moderation in global growth rates citing trade and growing uncertainty for business which will hurt investment due to U.S.—China trade tensions.

Getting fiscal policy right in the 2019 planning context means being prepared to navigate a potential economic shock over the next few years while aligning fiscal policy to long term policy objectives in a fiscally sustainable manner.

Year-over year growth in the Canadian economy now sits at 1.4 per cent. It is a modest growth rate—much higher than the growth rate going into the 2015 election, but still a significant deceleration from the 4.4 per cent growth rate peak in the spring of 2017. Weakness in the goods sector is restraining this growth rate. In addition, there has been ongoing weakness in investment raising concerns about the level of longer-term growth rates in Canada.

Notwithstanding the roller coaster ride in growth over the past four years, the economy now sits in a relatively good place—operating near its potential. The unemployment rate stands at 5.7 per cent for July, compared to 7.1 per cent in October 2015. The level of employment stands at 19,030 thousand, up from 18,007 thousand in October 2015. This is an impressive rate of job creation—up more about 40 per cent over the previous four years (2011

to 2015).

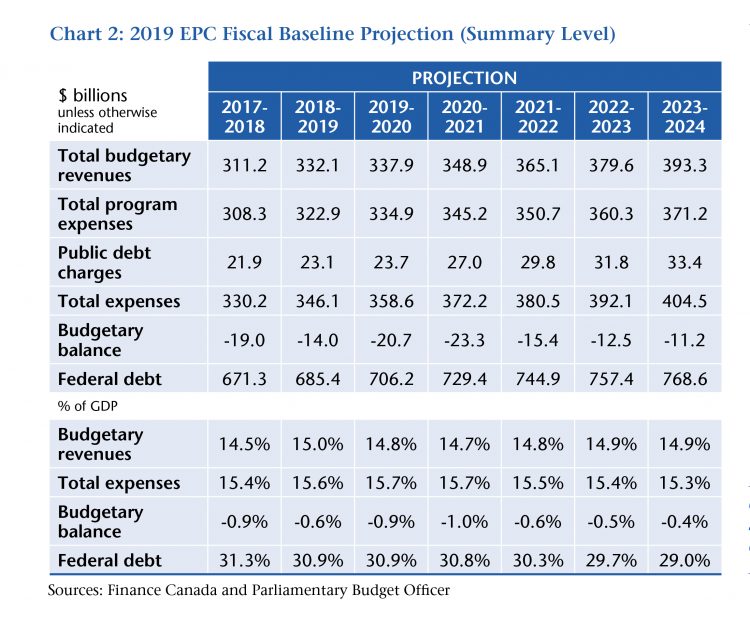

PBO released its election proposal costing (EPC) baseline projections in June 2019. It is assumed that all political parties will use it as their starting point in developing fiscal plans.

The PBO baseline assumptions are largely consistent with Budget 2019. Economic growth rates rebound in 2020 and hover around potential over the medium term. The unemployment rate remains at historic lows. Short- and long-term interest rates rise moderately over the short term and then stabilize. Overall price inflation is assumed to stay at 2 per cent. Oil prices remain flat. Any new finance minister would love to have this outlook become reality.

Based on these largely favourable economic planning assumptions, the PBO fiscal outlook has the projected federal deficit in the $20 to $25 billion range over the next two years, up from $14 billion. The low deficit figure in 2018-19 reflects strong growth in budgetary revenues, resulting in part from a strong labour market. Finance and PBO expect revenues to more in line with historical norms thereafter. Over the medium term, the budgetary deficit declines in nominal terms and as a percent of GDP, but is not eliminated.

In this baseline fiscal outlook, before new political party measures, which could be in the range of $2 to $5 billion a year, modest budgetary deficits of about 1 per cent of GDP are here to stay.

Is it responsible to run modest budgetary deficits over the medium term? What if all political parties simply add their PBO costed measures to this baseline? Would an extra $20 billion of debt after four years fundamentally change Canada’s long- term fiscal health? The answer—it depends.

Is it responsible to run modest budgetary deficits over the medium term? What if all political parties simply add their PBO costed measures to this baseline? Would an extra $20 billion of debt after four years fundamentally change Canada’s long- term fiscal health? The answer—it depends.

By and large, Canada could easily absorb modestly higher debt over the next medium term and remain fiscally sustainable over the long run. My guess is that is what most political parties plan to do—run higher budgetary deficits.

From a macroeconomic perspective, this is not likely the best policy. With an economy operating at potential (long term trend), a better path is for fiscal policy to be neutral with respect to growth (budgetary balance or small surpluses), not expansionary (structural budget deficits).

From a public policy perspective, a political case could be made for running modestly higher budgetary deficits. Clearly, economies like Canada are facing significant adjustment measures. We do not have plans with numbers to show what it will take to slow the increase in income disparity. We do not have plans with numbers to show the cost of adjustment to climate change. We do not have plans with numbers to show the cost of adjustment to the coming impact on employment of artificial intelligence and robotization. We know that we need to increase investments in our youth where disparities are large, as is the case for Indigenous children.

If political parties propose running higher budgetary deficits over the medium term (than the PBO election costing baseline), then citizens should demand a quid pro quo.

- As recommended by the IMF, Canada should have fiscal targets or a rule that constrains government spending. The targets or rule (involving the budgetary balance, debt and program spending) should be sensitive to changes in economic outcomes.

- Political parties should commit to open and transparent spending reviews before significant new spending is undertaken. Reallocation of spending should be based on program evaluations that are made publicly available. As fiscal space is being used up that will constrain future governments and generations, we should ensure all opportunities are undertaken to improve the quality of spending (e.g., performance, inclusion, longer-term investment)

- We need political parties to strengthen the link between fiscal policy and well-being of citizens. Other countries, including New Zealand—which tabled its first “wellbeing budget” in May—are already moving down this path. In this framework, budget measures and spending are presented to citizens in a way that focuses on what matters to well being (children, health, education, environment, communities etc). International organizations like the OECD are supporting this development with analytical tools that demonstrate the importance of a spending mix that supports inclusive growth.

Kevin Page, founding President and CEO of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy at University of Ottawa, was Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer.