Information and Communication Infrastructure Resiliency: Canada’s Invisible Security Risk

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

By Clara Geddes and Helaina Gaspard

March 25, 2025

The onslaught of President Donald Trump’s tariffs has pushed economic security to the forefront of the upcoming federal election. The shifting political relationship between Canada and the United States will require Canada to enhance its economic and continental security activities so that it is not perceived or targeted as vulnerable.

These efforts must include enhancing the resiliency of our information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure. The U.S.-Canada rift has already had an impact on internet service provision. With Ontario ripping up its $100 million deal with Trump affiliate Elon Musk’s Starlink as a protest against the tariffs, 15,000 homes and businesses risk losing the opportunity for satellite connection. At the same time, Quebec has a 3-year deal with Starlink that provides satellite connection for about 10,000 households. The deal expires in June and it isn’t clear yet how the province plans to respond. This standoff, and its potential repercussions, are a reminder of the varied and unpredictable threats to our connectivity networks that range from climate change to cyber attacks.

Our telecommunications networks, such as mobile and broadband, are critical infrastructure. Connectivity disruptions can result in significant cascading costs and repercussions. Consider the 2022 Rogers outage, which disrupted public services, payment processing, emergency service calls, etc. The incident gave Canada a taste of the potentially far-reaching impacts of telecommunication service disruptions.

IFSD recently hosted a roundtable (with funding from TELUS) to explore ICT resiliency. Participants included systems operators, government representatives, sectoral consultants and lobbyists, and academics from Canada and abroad.

The message was clear: fostering ICT resiliency is a multi-faceted and multi-actor effort. Economic security and social well-being are inextricably interconnected. This makes resiliency everyone’s concern, demanding collective action and investment.

Even before Trump’s tariffs, the federal government and Parliament, as well as business leaders, had been increasingly concerned with economic security, including threats to critical infrastructure, including ICT. This has been a priority for Liberal leader and Prime Minister Mark Carney. Carney’s economic plan highlighted the role of critical infrastructure in the economy and the risks posed by cyberthreats.

ICT infrastructure cannot be left out of the discussion on critical infrastructure and economic security. In 2023, nearly three-quarters of GDP by industry was service-based. From the purchasing of goods and services to the management of utilities to access to health care, ICT permeates all facets of economic and social life in Canada.

The federal government can play a role in fostering ICT resiliency by: 1) recognizing the importance of resiliency and coordinating actions; and 2) incenting planning for resiliency among operators and users.

The importance of resiliency

The federal government recognizes the risk of connectivity disruptions. For example, proposed legislation – Bill C-26, An Act respecting cyber security, amending the Telecommunications Act and making consequential amendments to other Acts – would add security to the Telecommunications Act as a policy objective.

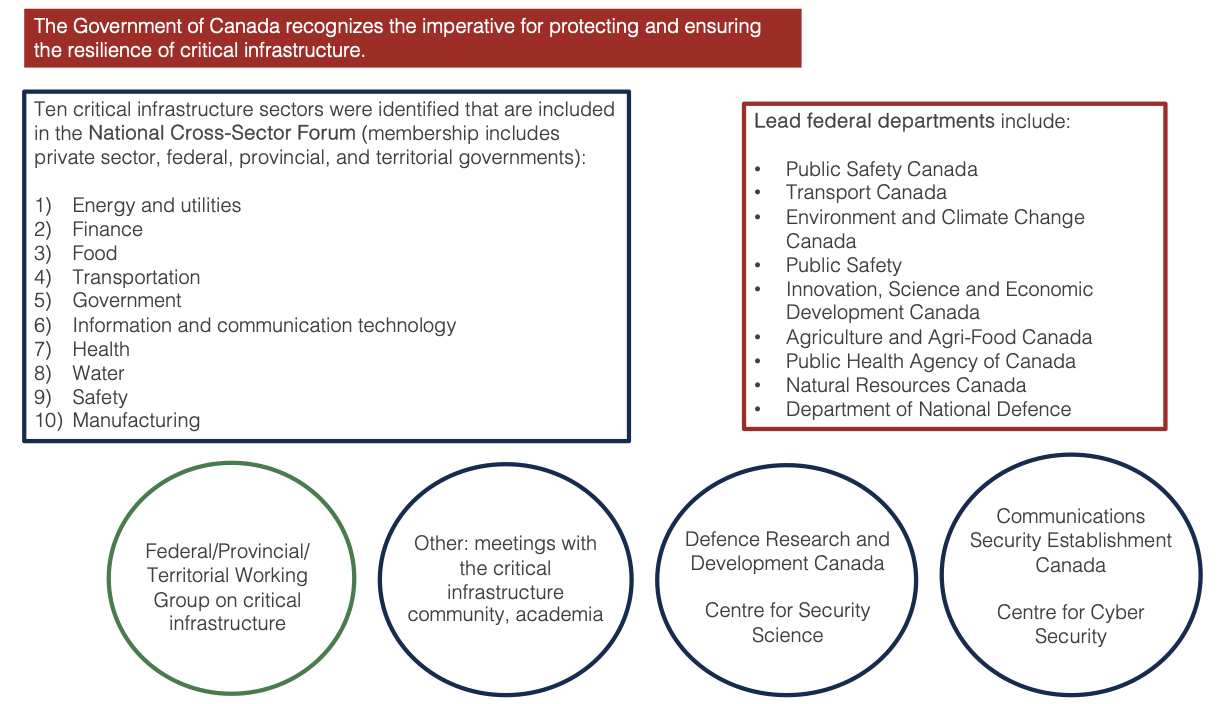

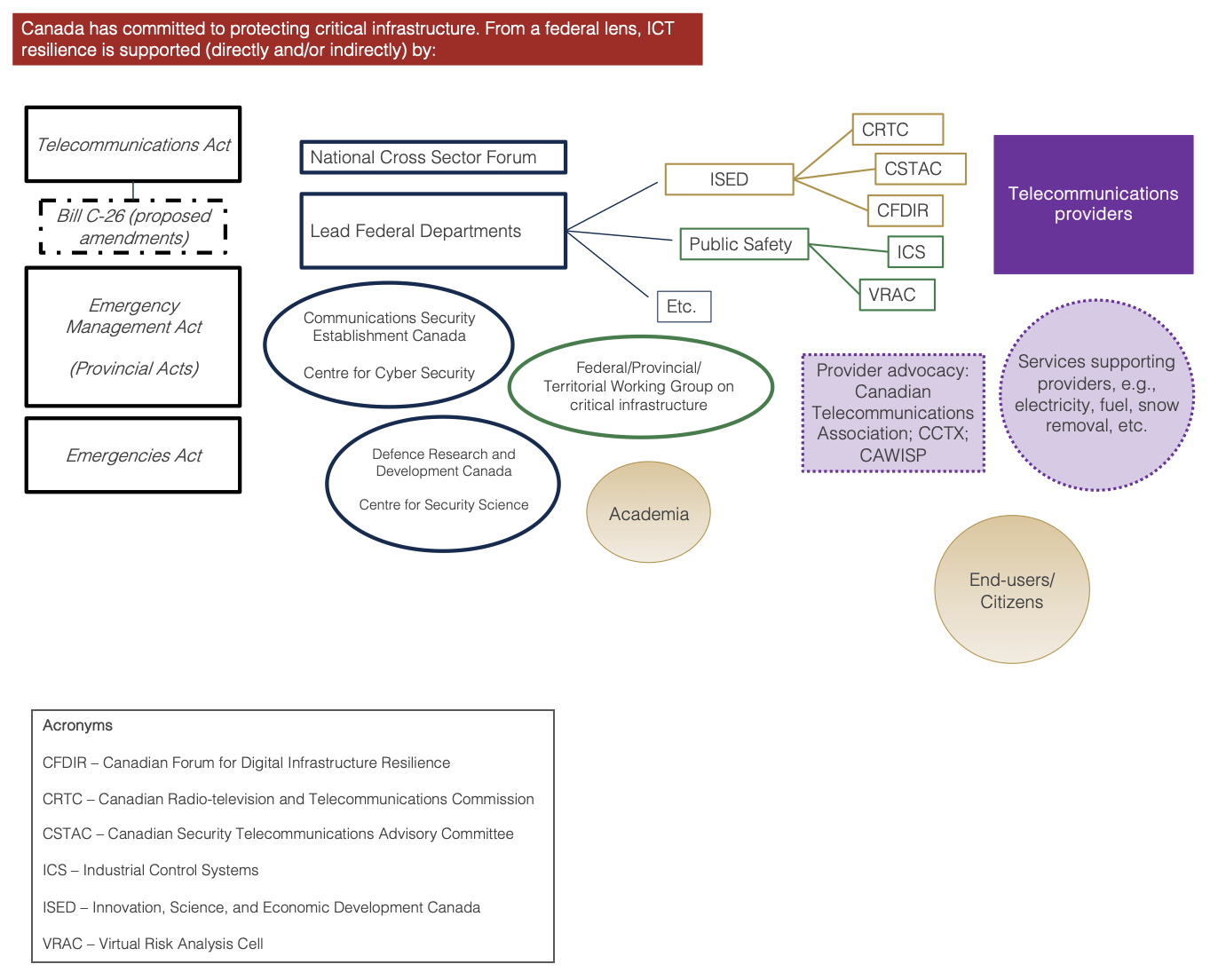

Given the importance of critical infrastructure, including ICT, the Government of Canada has announced strategies, convened actors, and declared commitments to protect and ensure its ICT resiliency. Below, Figure 1 depicts elements of the Government of Canada’s approach to ensuring the resiliency of critical infrastructure. In Figure 2, an overview of legislation, initiatives, and actors engaged directly or indirectly in ICT resiliency (from a federal viewpoint) is presented. The use of legislation such as the Emergency Management Act or Emergencies Act would be exceptional. It is expected that the departmental initiatives and centres engage consistently to anticipate and manage ICT risks. However, no department or center appears to take a coordinating role to ensure a whole of government approach to ICT resiliency.

While there are numerous reports, statements, and memoranda of understanding (MOU), from the outside, it is not clear who is coordinating planning and responses in Canada. Resiliency in ICT requires a whole of government approach (beyond ISED and CRTC). Laws, regulations, procurement practices, policy decisions, etc., have a direct influence on how ICT resiliency is planned and practiced.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The 2022 Memorandum of Understanding on Telecommunications Reliability (MOU) defined a protocol for shared emergency roaming during a critical network failure caused by an emergency. In the preamble to the MOU, “the importance of telecommunications quality and resiliency” is recognized as a driver for the arrangement. In addition, a 2022 decision from regulators in the United States is referenced, identifying mobile services as “a significant lifeline” in an emergency and disaster situations that require providers to establish procedures for roaming, mutual aid, and stakeholder/public communications in emergency circumstances. The MOU is recognition of the need to promote network resiliency through provider collaboration in emergency contexts.

Canada’s networks are resilient, due to facilities-based competition, but increasing threats makes the much more challenging to maintain.

In Canada, the Canadian Telecommunications Network Resiliency Working Group (a working group of the Canadian Security Telecommunications Advisory Committee (CSTAC), produced policy recommendations in March 2023 to advance network resiliency. There are five general recommendations: 1) establish network redundancy; 2) identify and mitigate single points of failure, e.g., geographic; 3) design physical to withstand shocks; 4) install underground cables; 5) establish business practices for rapid assessment and responsiveness. A series of more detailed recommendations for six key elements: core networks, physical structures, services and applications, internet services and infrastructure, access to networks, and processes, are included in the report. Composed of industry experts and ISED, the working group’s recommendations were operator focused, but there was a call for national action and legislation to protect ICT critical infrastructure.

Incenting planning for resiliency

Resiliency of networks and related delivery infrastructure could be incented at the front-end and back-end through two mechanisms: tax credits and a response fund.

A tax credit, spending by the government by reducing or eliminating a tax (revenue) opportunity on a payer, is a potential tool to incent providers to build resiliently, test frequently, and respond decisively to threats. Working with industry, the federal government could define the tax credit instrument, its terms, targets, and estimated costs.

A complement to the tax credit would be a response fund that would serve as a backstop for unforeseen risks. ICT resiliency requires participation from multiple stakeholders, including operators, government, and community. A fund to rebuild or respond to ICT-related emergencies could be useful in promoting broad-based access for a variety of actors and circumstances, e.g., New Zealand’s Natural Hazards Fund, funded through a levy on homeowners’ insurance.

There is a precedent for funds to incent actions and respond to occurrences federally. Consider for instance, the Broadband Fund, designed to incent operators to provide connectivity in underserved parts of the country; the On-Farm Climate Action Fund that provided resources to farmers to respond to climate change; or the Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund that provided communities impacted by climate change with resources to improve natural and structural infrastructure resiliency.

The federal government could also use a fund to incent actions that build resiliency. For example, the CRTC’s Broadband Fund is an application-based fund for specific projects that provide connectivity in underserved areas. The CRTC is currently considering repurposing some of the $150M fund to focus on resiliency.

Actions to support resiliency and implications of decisions extend beyond ICT operators. For instance, operators’ staff, law enforcement, etc., are involved in the costly responses to instances of copper theft.The federal government needs to coordinate among relevant actors to best respond to these localized disruptions.

Community-level considerations should also be included in emergency management. Citizens/end-users are the first to feel the impacts of any service disruptions and communities must have plans for their own resiliency. For instance, governments could encourage citizens/end-users to have a generator or backup power source to ensure broadband connectivity when the power is down.

Threats from climate change, geopolitical tensions and nefarious actors, human error, and technological changes require long-term plans to address them. While no amount of funding can eliminate risk, risk can be managed with appropriate and incented planning across groups of actors.

With economic security on the agenda, a new prime minister will have the opportunity to align actions and expenditures on ICT resiliency. The federal government must pursue its roles in coordinating, compelling, and convening to build resiliency and anticipate responses to ICT emergencies.

Clara Geddes, Economic Analyst at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD)

Helaina Gaspard, Managing Director at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD)